Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 10, 2015

DPS 2015: Pluto's small moons Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra [UPDATED]

EDIT Nov 13: The sizes I reported for Styx and Kerberos were not the most up-to-date ones. I have updated them with information from Hal Weaver. --ESL

How to make sense of a day and a half of packed scientific sessions and hallway conversation on Pluto? Based on past experience, it's best to cut a big problem into smaller pieces and take them on one at a time. So for my first post on results from the Division for Planetary Sciences meeting, I'm going to tell you about Pluto's small moons: Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. Here is a visual guide to the four:

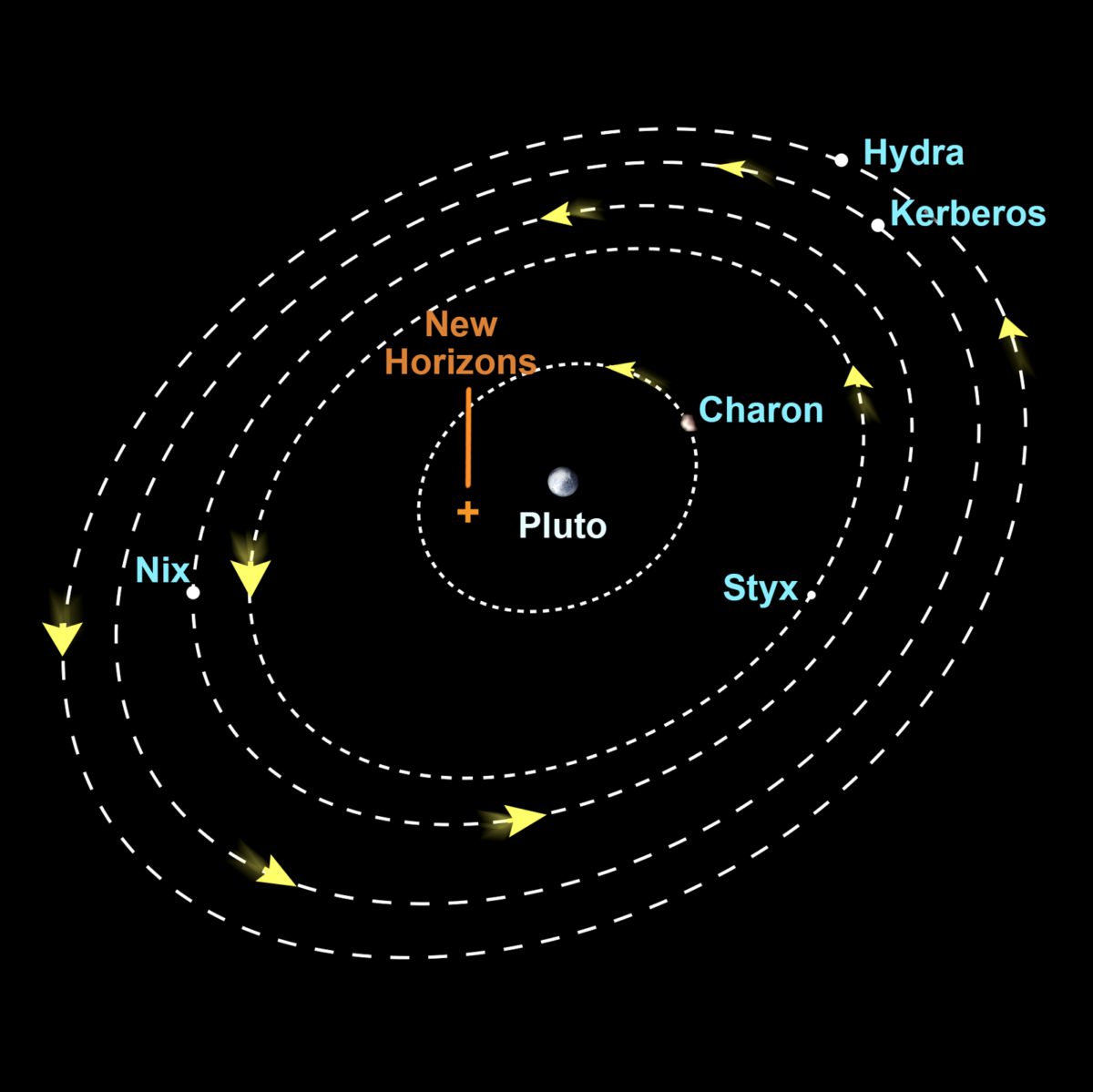

And a graphic that shows their positions with respect to New Horizons at the moment of closest approach. New Horizons crossed the equatorial plane of Pluto at a distance near Charon's orbit some time before closest approach, so it is "behind" everything else in the diagram here.

Here's a summary of the physical and orbital characteristics of these worlds as reported at the conference.

| Body | Magnitude | Semimajor axis (km) | Orbital period | Spin period (days) | Spin period (per orbit) | Dimensions (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Styx | 27 | 42,656 ± 78 | 20.162 | 3.239 | 6.22 | 10 x 5.3 |

| Nix | 23.5 | 48,694 ± 3 | 24.855 | 1.829 | 13.6 | 54 x 41 x 36 |

| Kerberos | 26.5 | 57,783 ± 19 | 32.168 | 5.33 | 6.04 | 12 x 7.5 |

| Hydra | 23.0 | 64,738 ± 3 | 38.202 | 0.4295 | 88.9 | 43 x 33 |

Sources: semimajor axes: Showalter and Hamilton 2015; orbit data: Mark Showalter; sizes: Bill McKinnon & Hal Weaver. | ||||||

The most surprising results are the rotation states of the moons. To explain why they're surprising, consider the regular satellites in the solar system. Very nearly all of the moons that formed around the planets -- the so-called regular moons -- are locked in synchronous rotation, where their rotational axes are perpendicular to the planets' equatorial planes, and where they rotate once for each orbit around the planet, keeping the same face of the moon pointed at the planet at all times. Charon and Pluto are mutually tidally locked. But Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, although lying in the Pluto-Charon equatorial plane in circular orbits, have wacky rotation states, with axes pointed every which way, and non-synchronous rotation. Hydra, in particular, rotates once in 10 hours!

Pluto's "pandemonium" moons Most inner moons in the solar system keep one face pointed toward their central planet; this animation shows that certainly isn’t the case with the small moons of Pluto, which behave like spinning tops. Pluto is shown at center with, in order from closest to farthest orbit, its moons Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra.Video: NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI / M. Showalter

The pole orientations are weird, too. Styx's pole is sideways (with an inclination of 82 degrees), and Nix's pole is oriented 132 degrees from Pluto's equatorial plane, meaning that it rotates "backwards". Not only that, but its rotation rate has increased by 10% since its discovery. At the press briefing, I asked Mark Showalter if Pluto's small moons were more like the outer, irregular satellites of giant planets than they were like the "ringmoons". He said no, because they are presumed to have formed within the Pluto system, but yes, in that Pluto appears to have no influence whatsoever on their rotation. "They should be paying more attention to their parent than they are," he said. But they are paying some attention: he pointed out that it's the outermost, Hydra, that's spinning fastest. Its spin is actually similar to lots of other Kuiper belt objects; it's fairly easy, he said, to make Kuiper belt objects spin at that rate from collisions. As you go inward from Hydra, the moons spin more slowly, perhaps having been slowed to their present rates by Pluto. The system is chaotic, but the fast spin rates actually stabilize the rotation states, meaning that it takes longer for them to change orientation and speed than it would if they were slow rotators.

Hal Weaver presented data on their brightness and color. All have quite bright surfaces, with albedo of "at least 60%", which is unusual in the Kuiper belt. They are neutral in color, intermediate in brightness and color between Pluto and Charon. Nix is slightly redder than Hydra. Their color is consistent with water ice composition. At least Nix and Hydra and possibly all of them appear to have formed as mergers of two or more smaller bodies, meaning Pluto had more moons originally. All this means they're likely collisional fragments, evidence for the collision that likely created the Pluto-Charon system in the first place. Unfortunately, it makes them poor proxies for small, primordial Kuiper belt objects, so it's a good thing New Horizons has found another small, likely primitive body to target (more on that later). The New Horizons team doesn't currently have a good explanation for how these little things maintained their bright color for the age of the solar system, or for why their axes are so tilted.

Both Nix and Hydra show several small craters. They have no visible boulders or layering, though there are color differences across their surfaces from those impact craters. The images of Kerberos and Styx are too low-resolution for craters to be visible. What the Kerberos images do show is that Kerberos is much, much smaller (and hence brighter) than the Showalter and Hamilton Hubble study predicted. Showalter told me that the cause of that incorrect prediction was an incorrect mass determination for Kerberos -- "so what we're learning is that it's tough to determine the masses of the moons." Robert Jacobson reported that Styx and Kerberos' masses are so low that the error bars are still bigger than the mass estimates for both.

New Horizons searched diligently for more moons, but the possibility of further small moons interior to Hydra has pretty much been ruled out now, as John Spencer showed in his presentation. It appears that the region of space from Styx to Hydra is "dynamically full" -- there's just no stable orbit for further small bodies -- and intense searches yielded no sign of anything bigger than about 2 kilometers across in the space between Pluto and Charon. If there are any undiscovered moons in the Pluto system, they are quite small. But even that is unlikely, as New Horizons' searches for rings around Pluto have also turned up nothing. Spencer held out some hope, saying the "ring story might change" as we get the rest of the data down from the spacecraft.

And yes, quite a lot more data still lie on the spacecraft. Our highest-resolution images of the small moons are on the ground, but there remains a higher-phase Nix image on the spacecraft, which will be good for topography. And a lot more color, composition, and ring search data remains to be downlinked.

Thanks to Matt Francis for sharing some of his notes from the afternoon Pluto session so that I could go see Ceres talks!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth