Asa Stahl • Sep 25, 2024

Could Europa Clipper find life?

For a mission that doesn’t aim to find alien life, Europa Clipper may come surprisingly close.

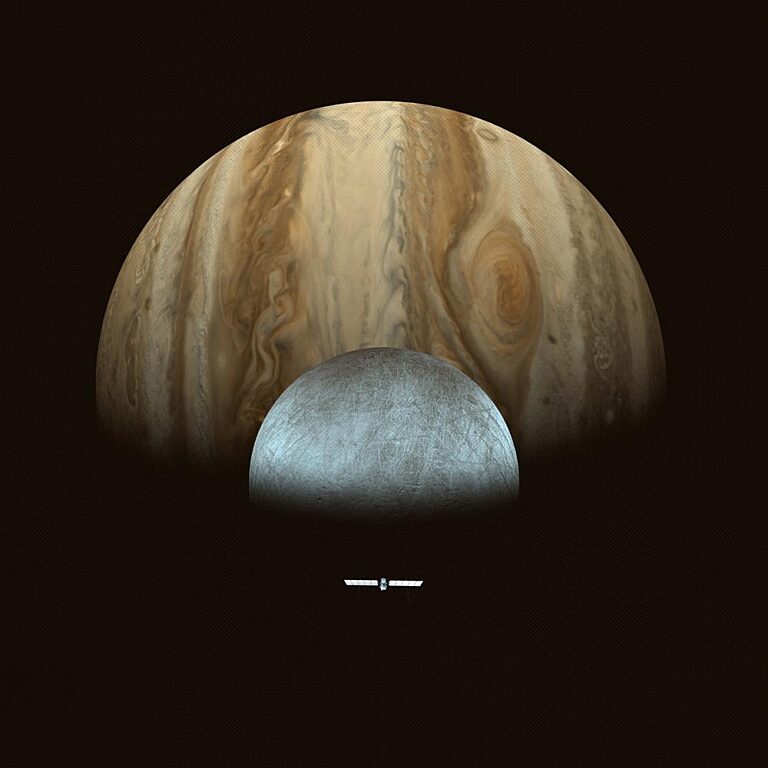

Through years of development up to today — only weeks away from the mission’s launch — NASA has been clear: Europa Clipper will not reveal alien life. The spacecraft will fly by Jupiter’s moon Europa, study the ocean of liquid water beneath the world’s icy surface, and investigate whether the right conditions for life might possibly exist there — but it won’t discover life itself. It’s not designed to.

Yet recent lab experiments hint that if microbial life does exist in Europa’s oceans, and if it were able to make it to space (say, trapped in an ice grain), its effect on the spacecraft could be recognizable. Even a tiny fraction of a microbe might lead to intriguing, detectable signals.

So: just how close could Europa Clipper come to finding life?

From ocean to orbit

We don’t know whether Europa’s oceans are habitable. Understanding whether the moon has the energy sources, environmental conditions, and chemical building blocks needed to host life is one of the main reasons why Europa Clipper has long been a top scientific priority. It’s also part of why Planetary Society members helped get the mission to the launchpad.

But if Europa does have microbes beneath a layer of ice, there are a couple different ways they might reach a spacecraft in orbit.

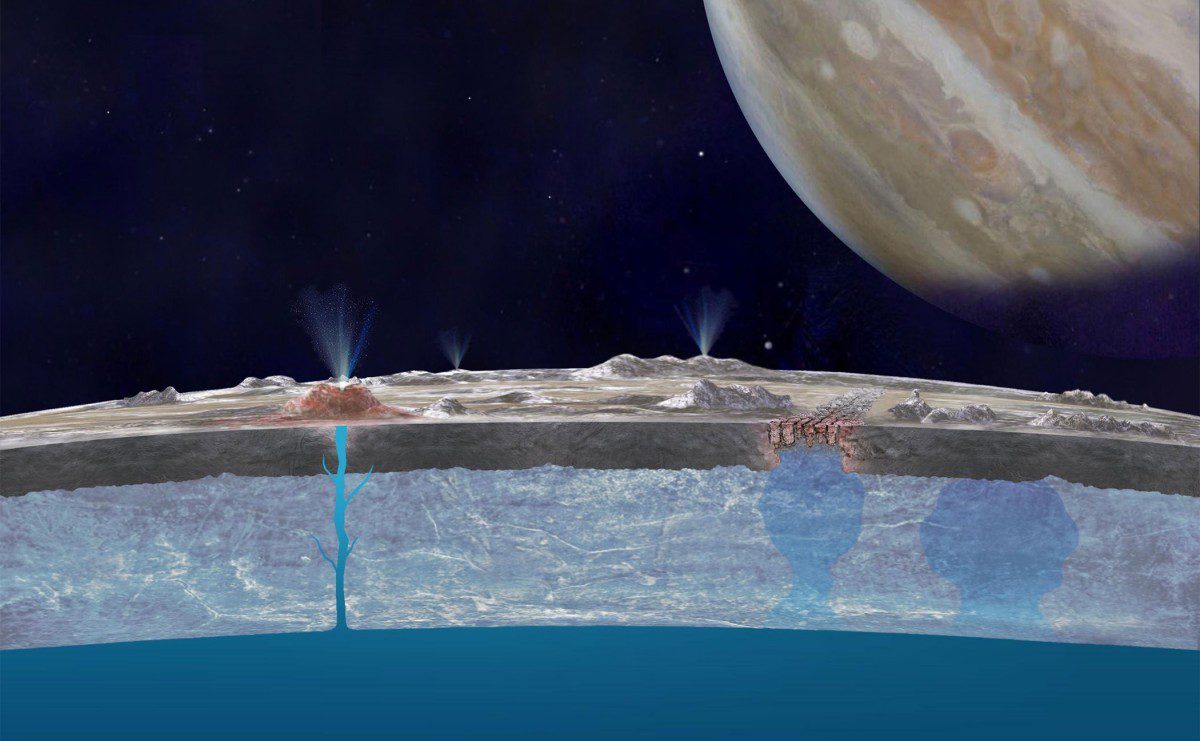

Ice and water vapor from the ocean could spray out into space through cracks in Europa’s surface. Though unconfirmed on Europa, these sorts of plumes are known to exist on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. NASA’s Cassini mission even flew through them, seizing the chance to learn more about what was hidden inside that world.

“Enceladus gave us evidence that this is not completely crazy,” said Jack “Hunter” Waite, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Alabama and past member of the Cassini team.

Waite, who now also works on the Europa Clipper mission, said that the plumes on Enceladus give many scientists hope that Europa will offer similar opportunities.

If Europa does host plumes — which is a debate in itself — they could provide a straightforward path for microbes to get from the ocean to a spacecraft flying overhead. Life drifting freely in the ocean, or floating in a scummy layer on top, could become trapped in ice grains that would then get launched away from Europa’s surface.

Riding the ice

Even if Europa doesn’t have plumes, material from within its ocean could still end up in nearby space. It’s possible that Europa’s ice sheet circulates, turning over on itself as warmer ice rises up and colder ice sinks down. A microbe trapped in ice might ride this slow churn up to the surface. Then, micrometeorite impacts could “sputter” it off into space and toward Europa Clipper.

This idea comes with its own problems. Pieces of lifeforms could be transformed, or even destroyed, as they travel through the ice. Once on the surface, radiation and micrometeorites would be damaging, too. Any effort to detect signs of life from Europa would have to understand how it might get altered on its way to us. According to Waite, that will be a challenge.

Thankfully, it’s not a puzzle that Europa Clipper would solve alone. ESA’s Juice mission, which has already launched, is slated to arrive at the icy moon two years after Europa Clipper as part of its larger survey of the Jupiter system. The Juice and Europa Clipper teams will work together to learn more about Europa and how its environment might affect possible signs of life. Hopefully, they’ll be able to use those lessons to guide Europa Clipper on the fly.

“There’s a lot to sort out,” said Waite. “It’ll be important to put that story together as we go.”

Signs of life

Say an alien microbe, perfectly preserved in ice, gets scooped up by Europa Clipper as the spacecraft flies past. Would we actually know what hit us?

There are two instruments aboard Europa Clipper that might see something compelling: the SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA), which is about the shape and size of a small snare drum, and the MAss Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration (MASPEX), which looks more like a death ray. Both will be able to capture ice grains. As the spacecraft passes Europa at thousands of kilometers per hour, these machines will collect samples, then identify them by measuring the masses of their basic chemical components.

On Earth, researchers have analyzed bacteria and other biological materials with technology that roughly mimics SUDA and MASPEX. They found signs of amino acids, DNA, and other building blocks of life. In one case, scientists predicted that these signals would be noticeable even if only one ten-thousandth of a cell were present within an ice grain.

At Europa, things won’t be as easy, Waite warned. Scientists would have to untangle any true signs of life from other chemicals that could confuse the picture. Some molecules from Europa may look related to life, but could also form without any life around. And the spacecraft itself could trigger false signs of life as it sheds material from its solar panels.

“You won’t know until you get there and try,” Waite added.

Hint or smoking gun?

None of that is a dealbreaker. With luck, there may be a way for a microbe to make it from Europa’s ocean to a distant spacecraft. With effort, scientists may figure out exactly how the moon’s environment would change, or contaminate, any signs of life.

But there is a more basic issue: SUDA and MASPEX can’t directly identify the largest molecules. Beyond a certain size, anything that hits the spacecraft will be broken up before either instrument can measure it. While some molecules are so large and complex that they very strongly point to life — think DNA — none would survive to be detected by Europa Clipper. Fragments of things like DNA would still be noticeable, but those would only be intriguing hints of life. They wouldn’t be a smoking gun.

“It’s not going to be a life detection,” Waite said, flat out. “This mission is not going to be a life discovery mission.”

The future, one step at a time

That’s not a design flaw. Confirming the existence of extraterrestrial life is a long scientific process, and Europa Clipper won’t be able to jump ahead. If it finds something interesting, a future mission could make a more targeted search for life using everything that Europa Clipper reveals. That spacecraft could land on Europa’s icy surface, collect samples, and relay information back to Earth.

No one knows just how close Europa Clipper might come to finding life. But the mission could transform our picture of Europa and its ability to host life. That, in turn, would change how we think about other worlds with subsurface oceans — including those outside of the Solar System.

And if there is life somewhere on Europa waiting to be discovered, Europa Clipper will bring us one step closer.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth