Jason Davis • Jun 20, 2023

Want to be a citizen astronomer and defend Earth from asteroids? Here are some tips.

Planetary defense is a team sport. Every night, the world’s professional sky surveys scan the heavens for near-Earth objects — space rocks that come close to Earth’s orbit. When these surveys find something, follow-up observations are required to determine an object’s trajectory and ascertain basic properties like shape, spin rate, and whether what initially looked like a single object is actually a binary pair.

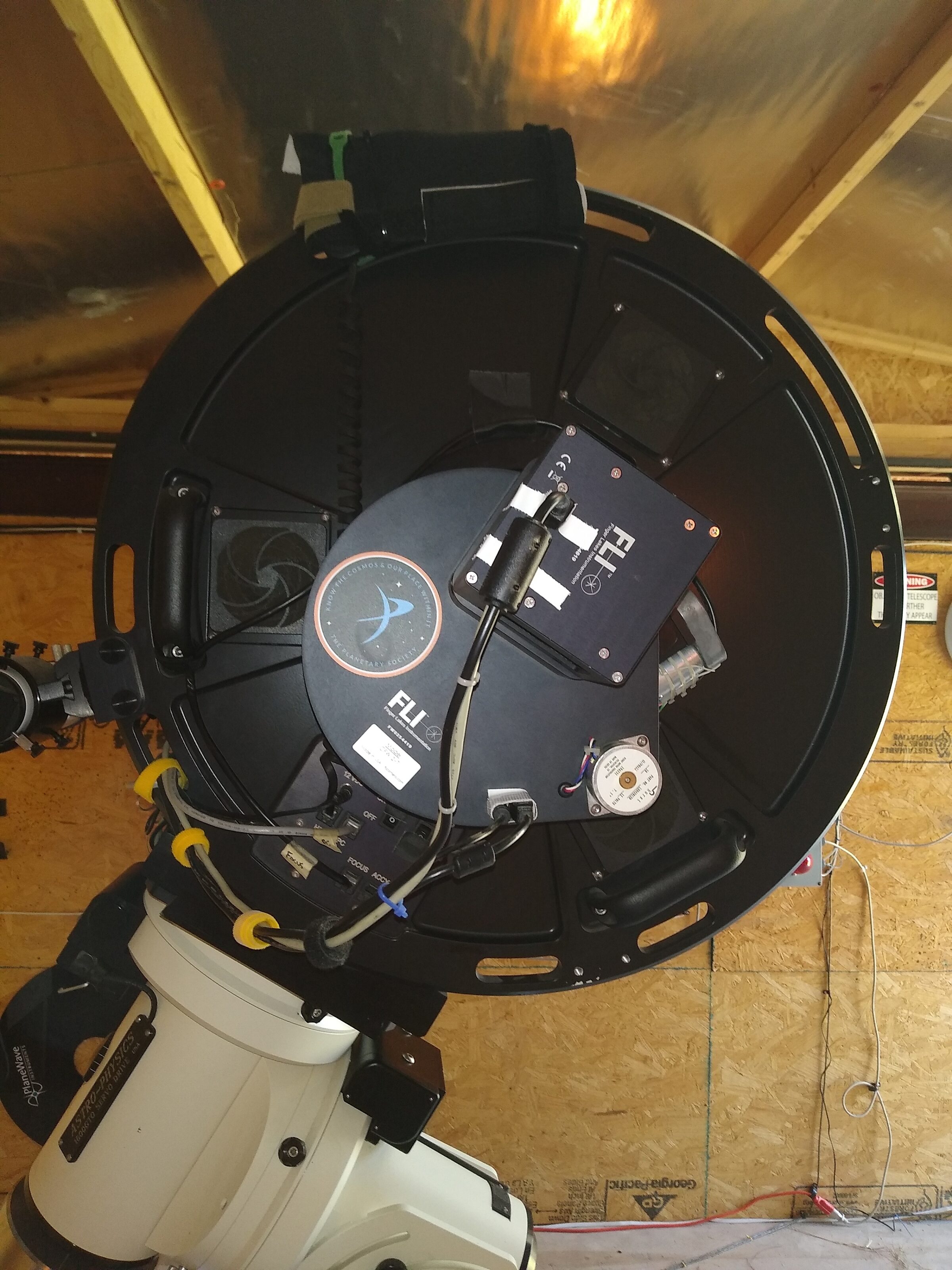

The arduous job of follow-up observations often falls to a global group of citizen astronomers, most of whom have separate day jobs and own or share small but sophisticated observatories. The Planetary Society supports these astronomers through our Shoemaker NEO Grant program.

These planetary defenders specialize in astrometry and photometry. Astrometry is the tracking and pinpointing of an object’s position, while photometry is measuring an object’s brightness over time. The scientifically precise data that citizen astronomers collect is sent to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, a global clearinghouse for small-body measurements. Agencies like NASA use MPC data to determine whether an asteroid is on course to hit our planet.

What does it take to become a citizen astronomer who captures scientific-grade asteroid data? We asked three of our past Shoemaker NEO grant winners for tips on how to assemble your own planetary defense observatory. They are:

Russell Durkee, a high school science teacher from Minneapolis, Minnesota who won grants in 2009, 2010 and 2019.

Gary Hug, a retired machinist from Scranton, Kansas who won grants in 2009, 2013, 2019, and 2021.

Cristóvão Jacques, an entrepreneur from Belo Horizonte, Brazil who won grants in 2000 and 2021.

Cost

Let’s get this out of the way first: Saving the world is a competitive and expensive hobby.

The Catalina Sky Survey’s NEOfixer website maintains a real-time, prioritized list of objects that need to be observed. To make a contribution, you’ve got to be fast: Each redundant observation becomes less and less useful.

Brighter objects are easier to observe, which pushes the emphasis toward dimmer objects that require larger and more sophisticated observatory setups. Our three Shoemaker winners estimated it would cost between $20,000 and $100,000 to replace their entire observing setups.

“Altogether this may cost as much as a used car or more,” said Russell Durkee. “In my case I have spent as much as a new Tesla over the last 20 years. I drive a 12-year-old Subaru.”

That doesn’t mean newbies are out of luck. Less-expensive setups may be limited in their ability to produce scientifically useful data, but they can help people hone their skills before making bigger investments. Additionally, there is a strong market for used equipment, making it easier to upgrade slowly over time.

If none of those options are feasible, there’s a free option, too: The Catalina Sky Survey allows citizen scientists to comb through its nightly images for asteroids. Citizen scientists can discover new objects without ever leaving the house.

Telescope and camera

Peering through the darkness of space for faint asteroids requires a good telescope and good camera.

The bigger the telescope, the more light from distant objects it can collect. Our Shoemaker winners recommended a mirror size of at least 0.28 meters (11 inches) in order to make useful asteroid measurements.

A common choice is a Schmidt-Cassegrain type of telescope, in which light bounces off the main mirror to a secondary mirror, and then back through a hole in the center of the main mirror. Cristóvão Jacques had a specific recommendation for beginners: a Celestron RASA.

The camera is how a telescope actually measures the Cosmos. Here, photons from distant objects fall onto a sensor, where they are measured and sent to computer software. The measurements a camera makes can be used to determine an asteroid’s position, shape, size, and spin rate.

There are two choices when it comes to telescope cameras: CCDs (Charge Coupled Devices) or CMOS (Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductors) cameras. CCDs were the gold standard for decades, until CMOS technology advanced to the point where both choices are viable.

Mount

You have to find asteroids before you can image them. Then, you have to track them as they move across the sky — sometimes, relatively quickly — all while compensating for Earth’s rotation.

To do this, you need a “GoTo”-style telescope mount connected to a computer. A good mount can move from target to target all night long, tracking various objects for imaging.

Among our Shoemaker winners’ recommendations: Meade offers good beginner-level mounts, while Software Bisque and Astro-Physics make solid high-end options.

Software and data

Critical to any observing setup is a computer outfitted with multiple software packages. The actual software needed varies from user to user. Conversations with our Shoemaker winners revealed a few common software packages:

NEOfixer, developed by the Catalina Sky Survey, provides a real-time, prioritized list of planetary defense targets.

MPO Canopus is an astrometry and photometry measurement tool.

Tycho is an astrometry and photometry measurement tool that can also find and track asteroids.

Astrometrica is an astrometry measurement tool.

TAO and SkySift are observatory automation and image processing tools.

Gary Hug likes Tycho because it tries to compensate for the stars an asteroid inevitably passes in front of, which throws off measurements.

“It's not perfect, but it tries to subtract out the star itself and leave you with just the asteroid magnitude,” he said.

One potentially overlooked requirement for scientifically valid asteroid observing is making sure your equipment knows precisely what time it is. Even a few seconds’ difference can muddle measurements.

Observatory and location

Large, heavy telescopes and mounts that require extensive setup and calibration can’t be moved back and forth from a house each night. Citizen astronomers either build a small backyard observatory, or team up with other astronomers to house their equipment at a remote location. Observatories typically need a concrete pad to minimize vibrations, and may be enclosed in sheds with “roll-off” roofs that retract for observing. Observatory equipment, including the roof, telescope, camera, and mount, can be set up for remote observing.

Observing dim asteroids requires dark skies, which are becoming scarce in much of the world. Elevation is another factor: The higher your telescope, the less atmosphere it has to peer through. Low-humidity areas are also better for observing, as are places with more cloud-free nights.

Once you’ve settled on a location and your observatory is operational, you’ll submit some sample data to the Minor Planet Center that shows you can collect quality observations. Then, you’ll be assigned a unique observatory code.

Patience is key

When asked what overall advice they’d give to would-be planetary defenders, our Shoemaker awardees counseled patience and a willingness to get to know their craft.

“You've got to really like tinkering with hardware, and really knowing your equipment and software inside and out,” said Russell Durkee. “You've got to be a person who likes not only the science of it but also the troubleshooting and learning really difficult things,” he said.

For citizen astronomers interested in photometry, the book “A Practical Guide to Lightcurve Photometry and Analysis” comes highly recommended. Additional reading recommendations can be found at MinorPlanet.info.

Building your own observatory to defend the Earth is a costly, time-consuming hobby. But the payoff is huge: Our Shoemaker winners are part of a small group that makes exciting and important contributions to the field of asteroid research. There are currently more than 32,000 known near-Earth asteroids, with many more waiting to be found and studied. There’s plenty of space for you to make an impact as a planetary defender.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth