Catching the passion with Charlene Anderson

Since its first issue in 1980, The Planetary Report has featured stunning pictures to help share the passion, beauty and joy of space exploration. If you’re a member who reads the print edition of this magazine, all of the images in our “Year in Pictures” feature were digital right up until the moment they were printed on the page you’re touching. We are fortunate to live in an era where scenes from Mars can be posted online for the entire world to enjoy — sometimes mere hours after they were captured.

What was the process like before the internet? To remind us, we spoke with Charlene Anderson, the first staff member hired at The Planetary Society after the organization was founded by Carl Sagan, Bruce Murray and Lou Friedman. From 1980 to 2012, Anderson was the editor of The Planetary Report. During her tenure, she also served as the organization’s associate director. The following conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

JASON DAVIS When the magazine started in 1980, how did you get your hands on space images?

CHARLENE ANDERSON Most of them came through the press office at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and we would get hard copies. Even at that point, they weren’t produced with a film negative from a camera like old-time photos were. They were manufactured from spacecraft data, and they came to us on photographic paper either from the press office or directly from the scientists themselves. At press conferences, when new photos were released, they would be handed to you in a Manila envelope with captions taped onto the back. You would get your precious envelope and run back down to the office with it.

JD Did you have some kind of cataloging system for them?

CA We had the great locking file cabinet in my office. We didn’t just have images from JPL. In the early ’80s, we had Venera pictures from Venus. Because of Carl and Lou’s connections with the Soviet Union, we would sometimes get them first. And at least in the case of the little Russian rover that landed on Mars back in the ’70s, we had the only picture of that in the United States. (Anderson is referring to the Mars 3 mission, which briefly transmitted from the surface in 1972. The image of the rover was taken prior to launch).

JD Wow.

CA But then, of course, we put them in The Planetary Report because one of the purposes of the magazine in the early days was to get our members the best possible copies of these images. That was one reason they joined The Planetary Society. We worked hard on the reproduction quality so they would be getting the best possible version of these pictures.

JD How did it feel when you were seeing these images and knew that especially in the case of the Soviet ones, you were one of the only people in the world who saw them before they were published?

CA It was a great responsibility, not only because the pictures were precious but because we were performing this service for our members and the general public. We took that seriously. That’s why we strove for the best possible quality when we reproduced these — because people couldn’t call them up on their computer. What can I say? I felt privileged.

JD Where did The Planetary Report fit in the media

landscape at the time? Were there any other magazines doing anything of

this magnitude?

CA There was

Astronomy Magazine and Sky & Telescope. They’ve gone through a lot

of changes, but they’re still there. But because we were smaller than

they were, we tried to compete on printing quality. That was our deal.

JD Do

you think you were successful? When I look back at our past issues,

they seem very impressive. It seems to me, not knowing what other

magazines looked like at that point, that you did compete.

CA

I’ll tell you a little anecdote. There was a young scientist at the

U.S. Geological Survey who was working on some new ways to process space

images, and he was very proud of what he was producing. At that point,

he was working on Io, and he slipped us some truly spectacular images

made from Voyager data. He told me that he wanted to see it first in The

Planetary Report because it was like sending your baby out into the

world, and he wanted it to appear at its best. We used to pull some

tricks, like occasionally paying for an extra color on the print when we

could run metallic ink, and it gave the image a pseudo

three-dimensional effect.

JD Speaking of Voyager, your career at The Planetary Society and the history of the organization itself really runs right alongside the Voyager encounters of the outer planets. What was it like seeing those images come in, especially in the case of Uranus and Neptune, when it was the first time we had seen them up close?

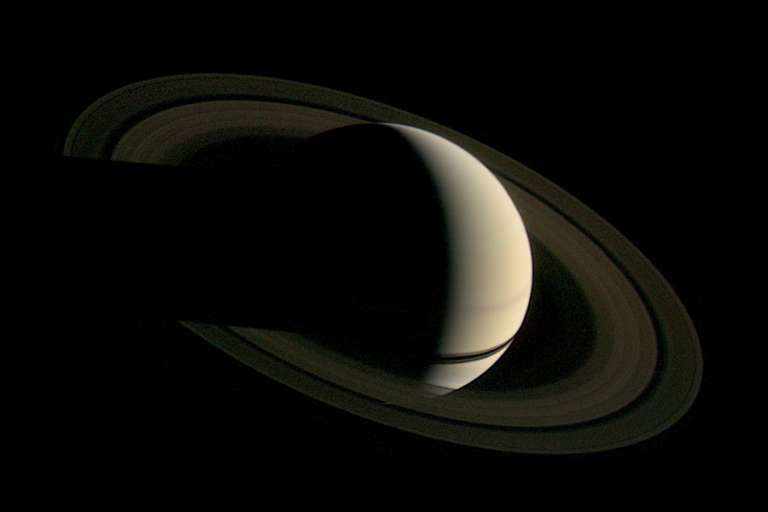

CA When you say “first time,” that was really a big deal. We would sit in the press room during the conferences when those photos were released and just gasp and feel privileged to know that outside of the scientists, we were the first ones seeing these worlds up close. The Voyagers are my all-time favorite missions. It was the first time we were seeing these worlds with such clarity. You really were an explorer riding along with the spacecraft. Pioneer had gone by Jupiter and Saturn earlier, but its cameras were not as wonderful as the ones the Voyagers carried. It was an adventure, and we knew it. There will never be anything like it again. By definition, if it’s the first, it’s special.

JD You were the first staff hire at The Planetary Society. Do you remember how you found out about the job and got hired?

CA I came over from The Cousteau Society. I had experience with ocean exploration, making it easy to transition to planetary exploration. In fact, at The Cousteau Society, Philippe Cousteau had an interest in space, and I was assigned space as my beat. So, I would report back to him on the discoveries that were coming out of the space program. Because I had the space beat, I got press releases from JPL, and they put out one announcing that this new organization called The Planetary Society was starting up. The address they gave was just down the hill from where I live. So I thought, “Well, I should check this out.” I went and talked to Lou Friedman. A couple weeks later, he asked if I’d ever considered leaving The Cousteau Society. And it happened to fall at a time when, yes, I was considering leaving. So, I helped start The Planetary Society.

JD Was it decided from the beginning that a magazine would be the major way that The Planetary Society did education and outreach? How important was it to Carl Sagan, Bruce Murray and Lou Friedman that we got space images out to the public?

CA At first, it was proposed that we would do a little four-page newsletter. And our consultants said, “Oh, no. You’re doing a magazine. These images are the best thing you have to get people excited about space, and you have to play them up.” So, that’s what we did.

JD Do you have a favorite space image?

CA I think I have two. I don’t know if you’ve noticed in past issues, but the planetary body I loved the most was Europa. After I saw those first Voyager images of the cracked surface, where you knew something was going on underneath all that ice, I fell in love with Europa. The other one would be Voyager 1’s departure shot of Saturn — the spacecraft looking back from where it came and this absolutely gorgeous planetary body beneath it.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

DonateThe Planetary Report • December Solstice

Help advance space science and exploration! Become a member of The Planetary Society and you'll receive the full PDF and print versions of The Planetary Report.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth