Jatan Mehta • Jul 19, 2018

How the Apollo missions transformed our understanding of the Moon’s origin

Where did the Moon come from? The origin of our cosmic neighbor is a fundamental question in planetary science. From Galileo’s first telescopic observations of the Moon to humans walking on its surface, our understanding of its origins has come a long way—yet it is far from complete.

There are multiple hypotheses that have attempted to explain how the Moon came to be. For this article, we’ll focus on the most popular one — The Giant Impact Hypothesis (GIH).

According to the GIH, 4.5 billion years ago, when the planets had just formed, a titanic collision took place. A young, Mars-sized planet (named Theia) collided with the early Earth. The impact ejected a huge amount of material. While some of this material escaped into space, the rest of it stayed in orbit, and consolidated to form the Moon.

For decades, the consensus of the planetary science community has been that the GIH is the best model to explain the formation of the Moon and account for its properties. While scientific literature on evidences for the GIH are varied in nature, in this article we focus on the Apollo missions. The Apollo missions represent a crucial dataset because they allowed us to test long-standing hypotheses using multiple in situ measurements, thanks to the 382 kilograms of samples that were brought back to Earth.

Data from the Apollo landings show that the Moon’s formation isn’t as simple as we first thought. The results have been difficult to reconcile and interpret. Let’s examine how the Apollo missions changed our understanding of the GIH.

Findings in support of the GIH

Magma ocean

An implication of the GIH is that the impact must have left the newly formed Moon in a molten state. It must have been encompassed in a vast magma ocean; the estimates for its depth are at least 500 kilometers. With time, this magma ocean would have crystallized and formed the mantle and crust of the Moon.

As crystallization of the magma ocean began, the heavier minerals, like olivine and pyroxene, would have sunk to form the lunar mantle. The lower density minerals, principally plagioclase, would float on top, crystallizing at a later stage to form the anorthosite crust. The GIH predicts that the elements in the magma that are incompatible would be sandwiched between the crust and mantle, forming what is known as a KREEP-rich magma.

KREEP is an acronym built from the letters K (Potassium), REE (rare-earth elements) and P (Phosphorus).

The samples brought back from Apollo 11 contained millimetric fragments from the rocky highlands nearby. The highlands represent material from the crust and the samples were found to be made of anorthosites. Moreover, KREEP-rich materials were also found in those samples. These findings all but confirmed the molten state of the ancient Moon, supporting the GIH.

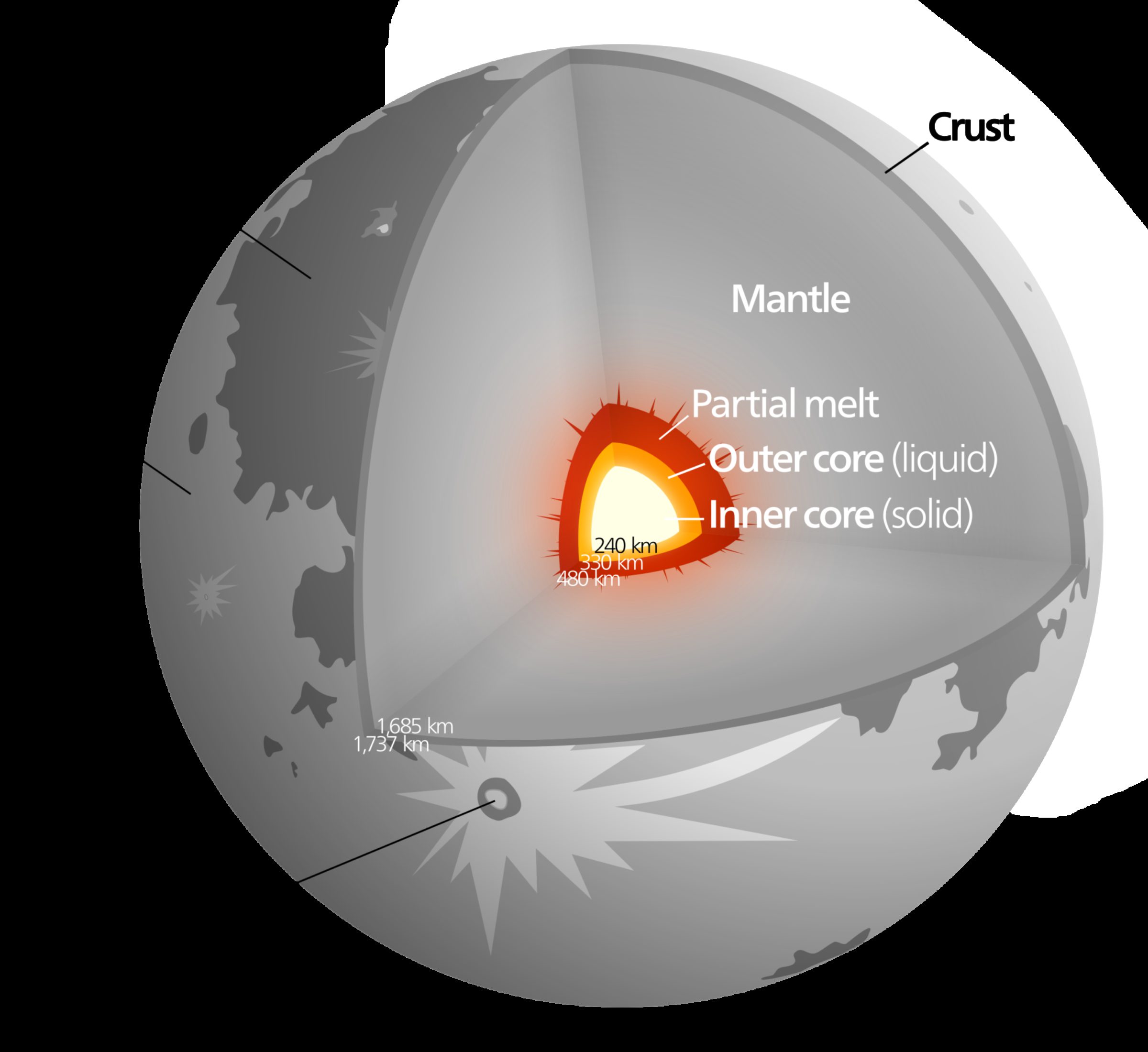

The lunar core

Also supporting the GIH were three independent experiments on Apollo missions that gave insights into the Moon’s interior. Data from the Passive Seismic Experiments, the Laser Ranging Retroreflectors and the Lunar Surface Magnetometers constrained the radius of the lunar core to be less than 450 kilometers. That means the lunar core, solid core and liquid one combined, represents only about 25 percent of the Moon’s radius, in contrast to about 50 percent for other terrestrial bodies, including Earth.

The GIH predicts that the Earth-Theia collision would result in Theia’s core getting absorbed into Earth’s core, leaving a smaller core for the Moon. The calculated size of the lunar core from these three independent experiments strongly agree with the GIH. It is also noteworthy that Earth has the highest density of all the planets in the solar system, which could be explained by the absorption of Theia’s core, given the proposed properties of the early Earth and Theia.

Volatile depletion

Another area of interest is volatiles—elements with low boiling points (nitrogen, water, carbon-dioxide, hydrogen, etc.). The low boiling points of volatiles mean that they deplete with time.

Large-scale volatile depletion on the Moon could have been due to two processes that existed at different times in the past. One is the evaporation of volatiles in the early formation era and the other is during ancient volcanism. The isotopes (different subatomic forms of the same element) found in present-day lunar volatiles can help us know the lunar history in this context.

Isotopes in volatiles deplete differently depending on the event, thereby telling us which of the above two processes was responsible for the volatile characteristics that we see now. Lighter isotopes of Zinc for example, are depleted in large amounts by evaporation during the formation of the Moon. But they are unaffected by volcanic processes.

In the lunar samples brought back to Earth, it was observed that the lighter isotopes of Zinc are less abundant than the heavier ones, which means that large amounts of volatile depletion took place due to evaporation in the early formation era. The result fits in line with the GIH prediction of a Moon lacking in a large amount of volatiles.

Findings against the GIH

Titanium isotopes

According to the GIH, if the Moon formed from the collision of two objects, it would inherit some of its material from Earth and some from Theia. One way to test that is to measure the titanium isotopic composition of the Moon and compare it to Earth’s. If the Moon indeed formed from both Earth’s and Theia’s materials, its titanium composition should be a mixture of both.

Titanium is a good element to measure because it doesn’t get vaporized easily and tends to remain solid or molten when exposed to high heat (which would have happened during early lunar formation). Thus, titanium should be in the same state it was early in the Moon’s history.

The comparative analysis of titanium in the Apollo samples indicates that the Moon’s titanium came from Earth alone. In stark contrast to that result, meteorites found on Earth contain large variations in titanium isotopes, indicating their distinct and varied origins.

The authors of a study from the University of Chicago initially found that the titanium isotopic composition of lunar and Earth samples are different. The team then corrected the results for changes due to cosmic ray bombardment; the Moon is unprotected from cosmic rays due to a lack of an atmosphere or magnetic field. After the results were corrected, it was clear that the Moon had the same titanium composition as Earth. If this is true, how could the GIH be correct?

One explanation could be that Theia had the same composition as Earth. Computer simulations of the GIH collision by Caltech researchers in 2007 calculated the origin of various materials relative to the Sun and how they were distributed in the early solar system. Unfortunately, they found the likelihood of Theia having an identical isotopic composition to the Earth to be less than 1%.

A shared water source for the Earth and the Moon

Much like the case with titanium, the isotopic compositions of lunar hydrogen and oxygen can be compared with that of Earth. The presence and origin of water in planetary interiors thus has important implications for understanding the evolution of planetary bodies.

The volcanic glass samples brought back from Apollo 15 and 17 had minor quantities of water in them. The isotopic composition of hydrogen in water in Moon’s mantle is nearly identical to that of water in Earth’s mantle. Likewise, the Moon’s oxygen isotopic composition, measured from Apollo 11, 12, 15, 16 and 17 samples, also show identical natures to that of Earth. When compared to other Solar System objects, like Mars, the Earth-Moon system is thus found to be compositionally distinct and identical.

This indicates that the process that formed the Moon involved objects that were created in this neighborhood of the Solar System, making the GIH even less feasible. The results also suggest that both Earth and the Moon had a significant component of water early in their early histories, possibly from the beginning of accretion, thus sharing the same water source.The nature of water in the lunar interior is thus not compatible with the GIH.

These results have strongly opposed the GIH as an explanation of the Moon’s formation, leaving us with more knowledge, yet farther away from a conclusion.

The takeaway

While various other modifications to the GIH have been proposed to incorporate both the evidence and counter-evidence, the fact remains that the Moon’s origin is still very much a mystery. The Apollo missions were largely in similar geological areas and yet it completely turned our understanding of the Moon’s origins on its head.

To solve the puzzle of the Moon’s origin, which is so intricately tied with that of the Earth itself, we need to go back to the Moon. We need access to rocks that lie deeper under the lunar surface, that haven’t been affected by meteorite impacts, cosmic rays and the solar wind. We also need to understand the origin of water on the lunar poles, and understand its thermal and chemical evolution.

In other words, we need more missions to the surface of the Moon.

There’s a renewed interest in going back to the Moon, this time tagged along with private capabilities for lunar soft-landing technologies. The next steps include evolving technologies to land at sites which pertain to larger scientific questions. Can we obtain samples from Shackleton Crater? Can we go to sites untouched by geological processes? What a profound success it would be to identify the origin of our dear Moon. For now, it remains a mystery.

Thanks to Phil Stooke from University of Western Ontario for fact-checking this article.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth