Mark Hilverda • Dec 12, 2013

A Tale of Two Posters: Sediment on Mars and Searching Jupiter's Rings

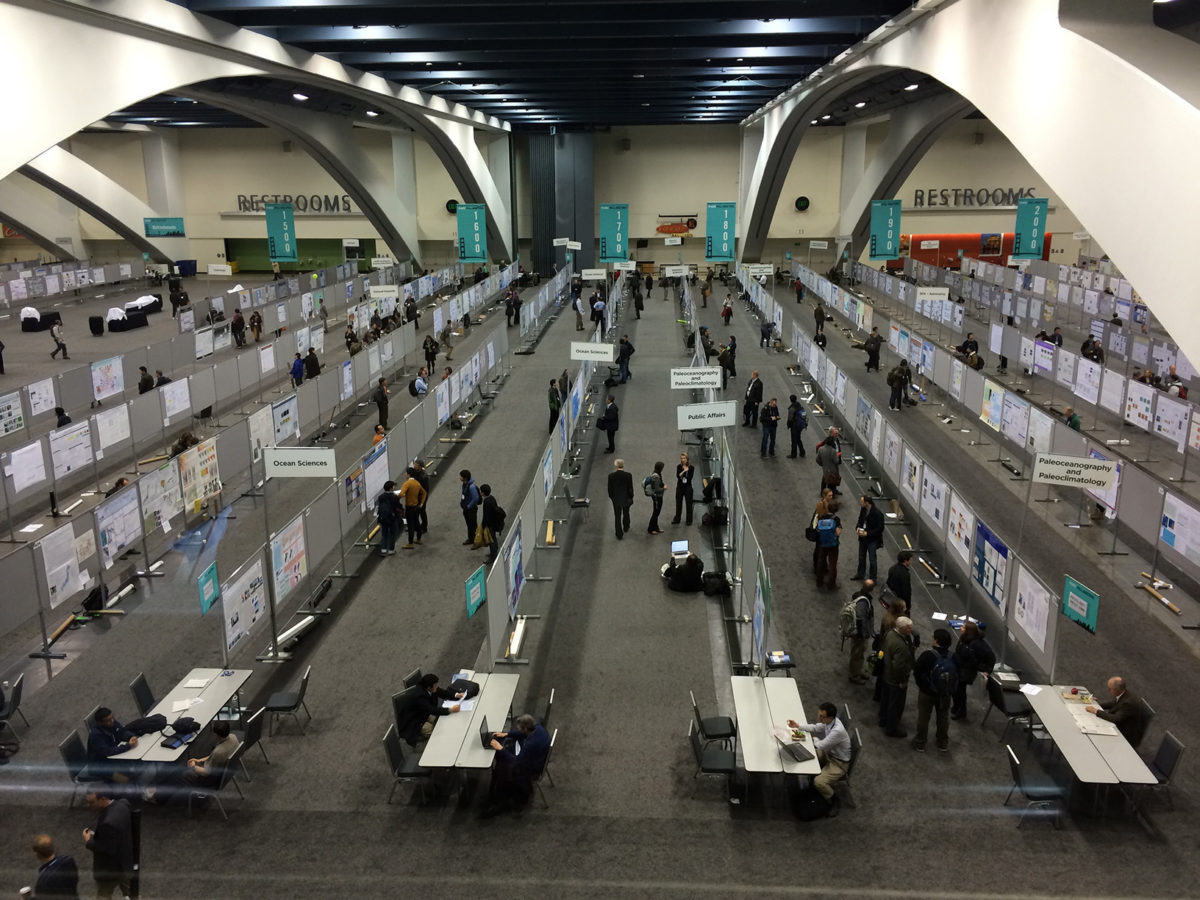

The AGU Fall Meeting is full of planetary science poster presentations, lectures, and meetings. It's an impressive event and I've been taking in as much planetary science as possible during the past few days. The oral presentations are typically 10 minutes in length with a few extra minutes for questions, so they are good for content presentation but minimal on interaction. On the other hand, poster presentations excel at interaction and provide a unique platform for deeper conversations with the scientists behind the research.

There are literally thousands of poster presentations at the AGU Fall Meeting with rotating presentation sessions throughout each day. Thankfully, the poster hall is divided by subject which makes exploring the posters relatively easy to manage.

The AGU Fall Meeting attracts scientists from around the world and I took advantage of the opportunity to explore some of the planetary science work that is being done internationally. Although I only discuss two such posters, many of the other posters are available in electronic format on the AGU ePosters webpage.

Sediment on Mars

Planetary scientists often use Earth analogs as a starting place for understanding processes on other planets. Investigating surface processes includes applying computer models, which work well for processes on Earth, but are often inadequate for other worlds due to differing conditions. Nikolaus Kuhn of the University of Basel in Switzerland, is studying how the gravity of Mars affects current geomorphological models. I had the chance to talk with him about his poster presentation "Sediment on Mars: Settling faster, moving slower."

Particle settling is an important part of sediment transport and understanding how related surface features form in planetary environments. Current models are based on Earth conditions and assume Earth's gravity. Kuhn describes that changing gravity on Mars is one factor, however fluid viscosity and electrostatic forces between liquids and particles would also change.

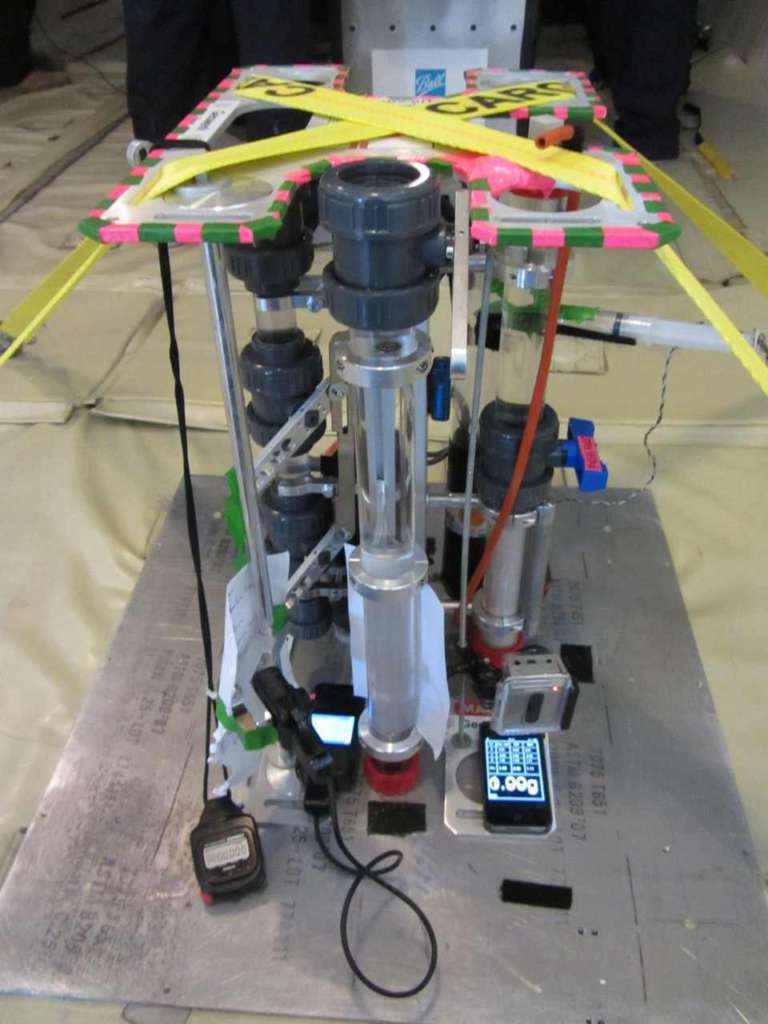

These relationships can be explored through particle settling experiments where particles are released within a settling tube containing a column of liquid and video is recorded to determine their settling velocities. So how do we get these tubes onto Mars to run the experiments? Getting to Mars is not yet easy, but fortunately Kuhn can simulate reduced gravity using parabolic flights, where an airplane follows a near parabolic flight path relative to the center of the Earth.

The experiments require careful design and planning and a lot of practice prior to flying as there is only 25 seconds where conditions are appropriate for running the experiments. The other challenge is the physical operating conditions - some scientists apparently handle reduced gravity better than others.

Kuhn successfully demonstrated that running short duration settling experiments under these flight conditions is possible. Initial results indicate that settling velocities on Mars are underestimated by 20% when using non-calibrated Earth models. The good news is that experiments like Kuhn's can be carried out to improve the application of existing geomorphological models to other worlds.

Searching Jupiter's Rings with Juno

The Juno spacecraft, currently on its way to Jupiter, is full of useful instrumentation. The magnetometers on Juno, which will investigate Jupiter's magnetosphere, are accompanied by four star tracking cameras for precise positioning control. Anastassia Malinnikova Bang of DTU Space, National Space Institute in Denmark, described to me how scientists will also be using these cameras to explore Jupiter's faint ring system.

The star tracking cameras are low-light instruments that can also identify and image non-stellar objects. This was most recently demonstrated during Juno's October 2013 Earth flyby when Juno captured a series of images of the Earth-Moon system during October 6-9, 2013. Earlier this week NASA released a video composed from these images showing the Earth and Moon's orbital dance.

Earth and Moon Seen by Passing Juno Spacecraft When NASA's Juno spacecraft flew past Earth on Oct. 9, 2013, it received a boost in speed of more than 8,800 mph (about 7.3 kilometer per second), which set it on course for a July 4, 2016, rendezvous with Jupiter. One of Juno's sensors, a special kind of camera optimized to track faint stars, also had a unique view of the Earth-moon system. The result was an intriguing, low-resolution glimpse of what our world would look like to a visitor from afar.Video: NASA / JPL

The Earth flyby also allowed scientists to optimize plans for studying the ring system of Jupiter. Bang explains that the cameras are even able to detect minor bodies with sizes less than 1 km (as long as their apparent magnitude is brighter than V=6.7). The star tracking system will have the opportunity to study the ring system during 33 orbits of the Juno science mission.

Until this poster session I was unaware of plans to explore Jupiter's ring system for new minor bodies during Juno’s mission. I now share Anastassia Bang's enthusiasm for this portion of the mission and am excited to see what new small worlds lurk within Jupiter's ring system.

Exploring Posters

Poster sessions are, of course, not unique to the AGU Fall Meeting but popular at many conferences. Although you can often simply download and read posters, I've found that the real benefit comes from attending the poster presentations in person. The opportunity to discuss the topics in depth with the people behind the research brings a level of clarity not possible from reading a poster by itself. The other benefit is that enthusiasm is contagious - you often walk away being as excited as the scientists are about their research.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth