Emily Lakdawalla • Apr 18, 2012

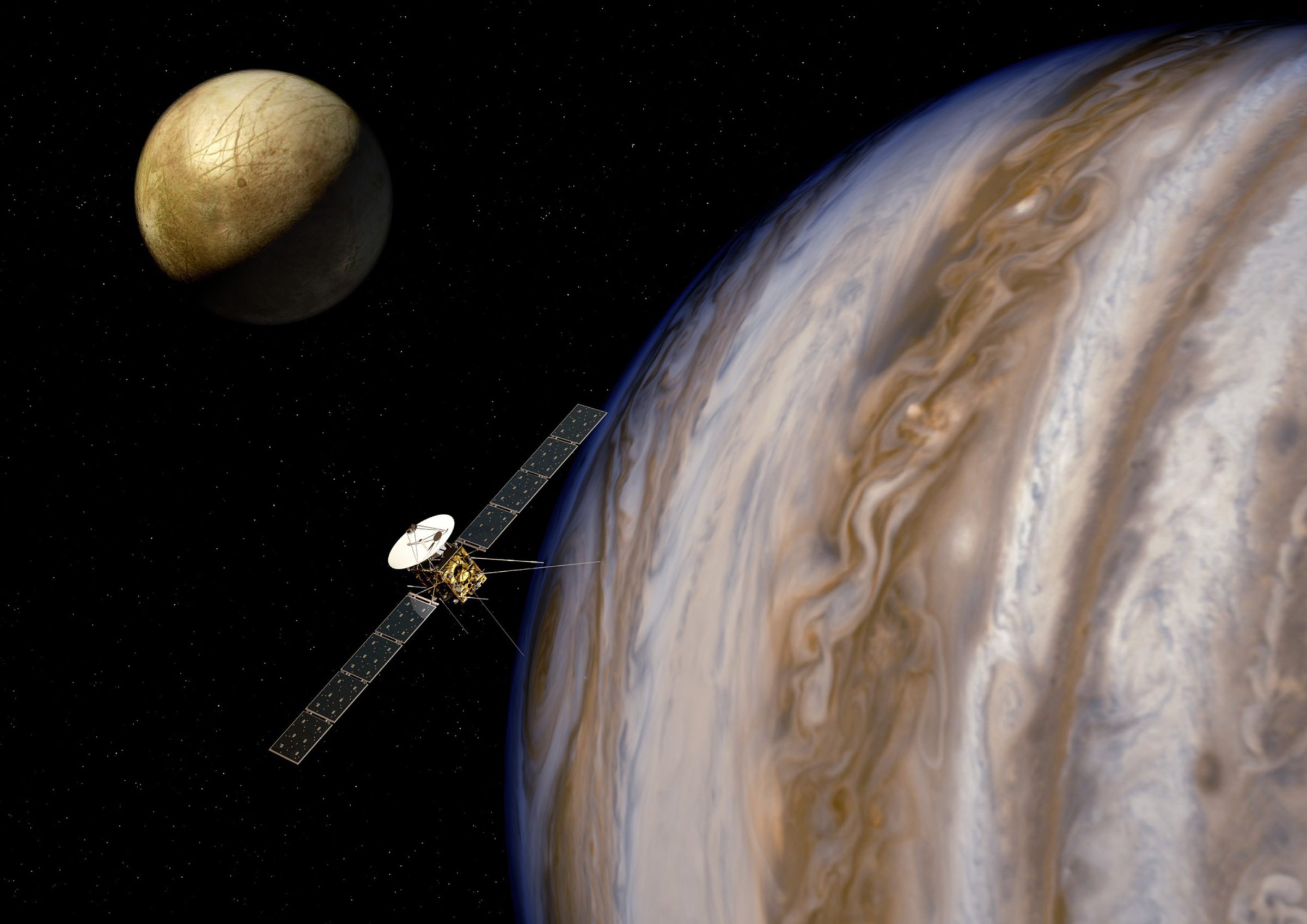

JUICE: Europe's next mission to Jupiter?

The Twitterverse is buzzing this morning with news that the Science Programme Committee of the European Space Agency has recommended that the next large European mission be JUICE, a mission to explore the three icy Galilean satellites and eventually to orbit Ganymede. The recommendation is not binding; it must be voted upon (a simple majority vote, according to BBC News), at a meeting of the Science Programme Committee, consisting of representatives of all 19 ESA member states, on May 2. The committee is likely to green-light this recommendation, but it shouldn't be taken as a certain decision just yet.

JUICE is being recommended over ATHENA (an x-ray observatory) and NGO (a gravitational wave observatory). It would launch in June 2022, enter Jupiter orbit in January 2030, and end in Ganymede orbit in June 2033. It is a concept that has been modified from JGO, the Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter, originally conceived as Europe's half of a US-Europe two-spacecraft mission to Jupiter, where NASA had originally proposed to provide a Jupiter Europa Orbiter. NASA canceled its plans to participate in that mission just as it canceled its participation in ExoMars more recently, and as with ExoMars, ESA appears ready to go forward without the USA. In fact, ESA has modified the originally proposed JGO mission to incorporate some of the science goals that would have been accomplished by NASA's Europa mission.

Here's the mission description and profile from the ESA document:

Science goals

The JUICE mission will visit the Jupiter system concentrating on the characterization of Ganymede, Europa and Callisto as planetary objects and potential habitats and on the exploration of the Jupiter system considered as an archetype for gas giants in the solar system and elsewhere. The focus of JUICE is to characterize the conditions that may have led to the emergence of habitable environments among the Jovian icy satellites, with special emphasis on the three ocean-bearing worlds, Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto. The mission will also focus on characterizing the diversity of processes in the Jupiter system which may be required in order to provide a stable environment at Ganymede, Europa and Callisto on geologic time scales, including gravitational coupling between the Galilean satellites and their long term tidal influence on the system as a whole.

Mission profile

The mission will be launched in June 2022 by an Ariane 5 ECA and will perform a 7.5 yr cruise toward Jupiter based on an Earth-Venus-Earth-Earth gravitational assist. The Jupiter orbit insertion will be performed in January 2030, and will be followed by a tour of the Jupiter system, comprising a transfer to Callisto (11 months), a phase studying Europa (with 2 flybys) and Callisto (with 3 flybys) lasting one month, a "Jupiter high-latitude phase" that includes 9 Callisto flybys (lasting 9 months) and the transfer to Ganymede (lasting 11 months). In September 2032 the spacecraft is inserted into orbit around Ganymede, starting with elliptical and high altitude circular orbits (for 5 months) followed by a phase in a medium altitude (500 km) circular orbit (3 months) and by a final phase in low altitude (200 km) circular orbit (1 month). The end of the nominal mission is foreseen in June 2033.

Spacecraft description

The spacecraft is 3-axis stabilised, and powered by solar panels, providing around 650 W at end of mission. Communication to Earth is provided by a fixed 3.2 m diameter high-gain antenna, in X and Ka bands, with a downlink capacity of at least 1.4 Gbit/day. To perform its tour of the Jupiter system the spacecraft will have a ΔV capability of 2700 m/s, and the shielding will limit radiation to 240 krad at the centre of a 10 mm Al solid sphere. The spacecraft dry mass at launch will be approximately 1.8 tons. While the actual payload will be chosen through a competitive AO process, the study has identified a model payload based on a suite of 11 instrument totalling 104 kg. These comprise cameras, spectrometers, a sub-mm wave instrument, a laser altimeter, an ice-penetrating radar, a magnetometer, a particle package, a radio and plasma wave instrument as well as a radio science instrument and ultra-stable oscillator.

A separate document, a presentation to the Outer Planets Assessment Group meeting in March 2012, details the model payload (thanks to Van Kane for this link):

- Narrow-angle camera

- Wide-angle camera

- Visible Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging Spectrometer

- UV Imaging Spectrometer

- Sub-millimeter Wave Instrument

- Magnetometer

- Radio and Plasma Wave Instrument

- Particle and Plasma Instrument - Ion Neutral Mass Spectrometer

- Laser Altimeter

- Ice Penetrating Radar

- Radio Science Instrument

This selection -- if it is accepted -- represents a big win for planetary science and a big loss for space-based astrophysics in Europe. Which is, one can't help but notice, opposite to what the currently-proposed NASA budget represents.

I'm pretty ignorant of the internal and external politics involved in these decisions, and also of the relative merits of JUICE, ATHENA, and NGO, so while I admit I'm happy the planetary mission got selected, I don't feel qualified to comment on whether it should have or shouldn't have been the one that ESA picked. But, as a member of the American public, I can't help but see this decision as Europe stepping in to the sucking vacuum left by NASA in the exploration of the outer planets. NASA's inability to follow up on decades of spectacular successes in outer solar system exploration with any mission beyond Cassini's end in 2017 leaves an opportunity for Europe to take over the leadership of Earth's exploration of the solar system beyond the asteroid belt. It remains a challenge that Europe doesn't currently have the capability to produce radioisotope power sources for spacecraft; limited to solar power at present, that means Europe can't get beyond Jupiter. But Jupiter is far enough, for now.

The outer planets science community is a small and international one, so for sure there will be American participation in the science team, and probably also in the payload; the ESA document says specifically that "NASA has expressed an interest in contributing to the payload." Science instruments on ESA missions work differently from NASA. They aren't paid for by ESA; ESA builds and pays for the spacecraft, but different member states propose, build, and operate the science instruments using their own funds. ESA estimates that the spacecraft will cost €830 million and that ESA member states will spend an estimated €241 million to build instruments. NASA may contribute up to €68 million toward the payload. I hope it contributes the full amount; it'd be hard to imagine a way to get more bang for one's bucks than to pay for a couple of instruments and 10 or 20 scientists to work on a mission being built, developed, launched, and operated by someone else.

But I sure wish we were launching a Europa orbiter alongside this one.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth