Pat Donohue • Feb 03, 2012

Six days in the crater (day one)

The following is the first in a series of posts based on field notes and memories supplemented by background reading material from the Meteor Crater Field Camp that was held from October 17-23, 2010. The field camp was run under the NASA Lunar Science Institute and headed by Dr. David Kring of the Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Twenty-two of us are spread out between three Chevy Suburbans, and it's strange having legroom on a geology expedition. Not that there's far to go. We are camped out in an RV park a mere 5.5 miles from our field site: Barringer Meteorite Crater. This is the first day of the first ever Meteor Crater Field Camp, and we are making the first trip first thing in the morning to my first visit to any crater, ever. Everyone's ready to get started, and we don't have long to wait. Our first stop is approximately fifteen feet outside the gates of our campsite, and we step out of the vehicles after realizing the stop wasn't because of a forgotten water bottle or notebook.

At 5.5 miles out there's not much of the crater to see and so we huddle around Dr. Kring, our fearless leader. He asks us to imagine standing at this exact spot 49,000 years ago* as Meteor Crater formed. "What would you see?" he asks us. Slowly we find our voices: A streak of light and a flash. A fireball. Wind whipping across the plains. A massive volume of ejected material rushing toward you. Then nothing because you are dead.

We learn we wouldn't even last that long. At this distance the shock wave would reach you in less than a second, turning you inside out before the wind and heat simultaneously flash-cooked your body as it tumbled away in pieces with the desert sage. Oh well. Someone luckier and further away would have seen quite the show.

49,000 years later, as we pile back into the vans, it's mostly sunny and warming past 50°F on the high desert plains of Arizona.

[*On the basis of thermoluminescence, 26Al, 10Be, and 36Cl studies, it's generally agreed that Meteor Crater formed 48 to 49 thousand years ago. More recently, updated 36Cl reference material argues for an older age of 60 to 65 thousand years.]

On the docket for our first day at the crater is a 3.7 kilometer (2.3 mile) hike along the rim, about 1.8 km clockwise before lunch, then retracing our steps counterclockwise. There's House Rock (also known as Monument Rock), the largest (intact) boulder on the crater rim at about 10 meters tall. Pile on two more House Rocks and you'd have a reasonable estimate of the meteorite diameter. And maybe at one time there really was another House Rock or two on top. Surface exposure age dates from the top of House Rock are younger than the 49,000-year formation age.

It wouldn't be surprising if House Rock had initially been covered by ejecta. Erosion and weathering is evident everywhere at the crater. A gully running downslope beneath the crater museum rapidly cut through three layers of authigenic breccia, both exposing and halfway eroding a projectile fragment over a two year period. The breccias are so friable that when we later head into the crater, we aren't allowed to touch or even go near the left side of the gully where the projectile is exposed.

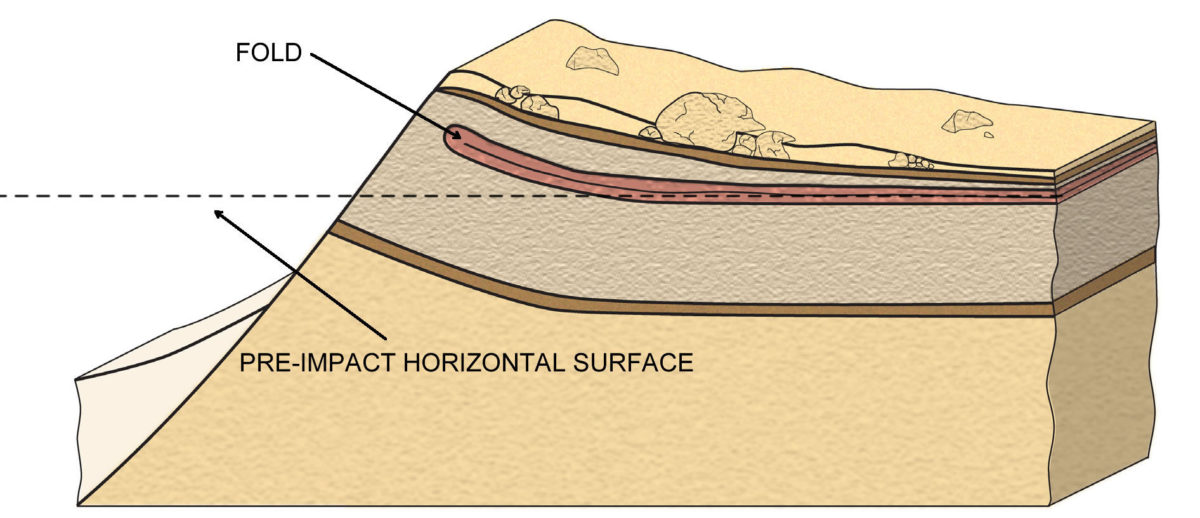

On our counterclockwise hike back we generate a little erosion of our own by scrambling down the crater wall a bit from House Rock to see something (else) awesome. We start out on Kaibab limestone on the crater rim and walk down through Moenkopi formation, and end up back at Kaibab. The top slice of bread in the Kaibab-Moenkopi-Kaibab sandwich is ejected, overturned Kaibab. The bottom slice is in-situ Kaibab. And the meaty Moenkopi center is where it gets interesting. Look at the photo below. Both members of the Moenkopi are visible here. The pale reddish brown Wupatki (at left) is a massive sandstone underlying the dark, reddish brown fissile siltstone called the Moqui. The surrounding pale/tan blocks are dominantly Kaibab (limestone/dolostone), though most shown here are loose boulders.

Originally horizontal beds were uplifted during impact and now dip away from the crater. In the center of the above image, the Moqui member -- the surface unit at the time -- takes a sharp turn and winds up parallel to the crater wall. This is an exposed portion of a fold hinge, where a flap of target material was overturned to create an inverted stratigraphic sequence.

There's so much more to see at the crater. Sand fields, tear faults, shocked quartz...and we're still just getting started!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth