Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 26, 2012

Parallel planetary processes create semantic headaches

So here's a semantic problem I ran into today. Consider this photo, a radar image of the Congo river from Envisat.

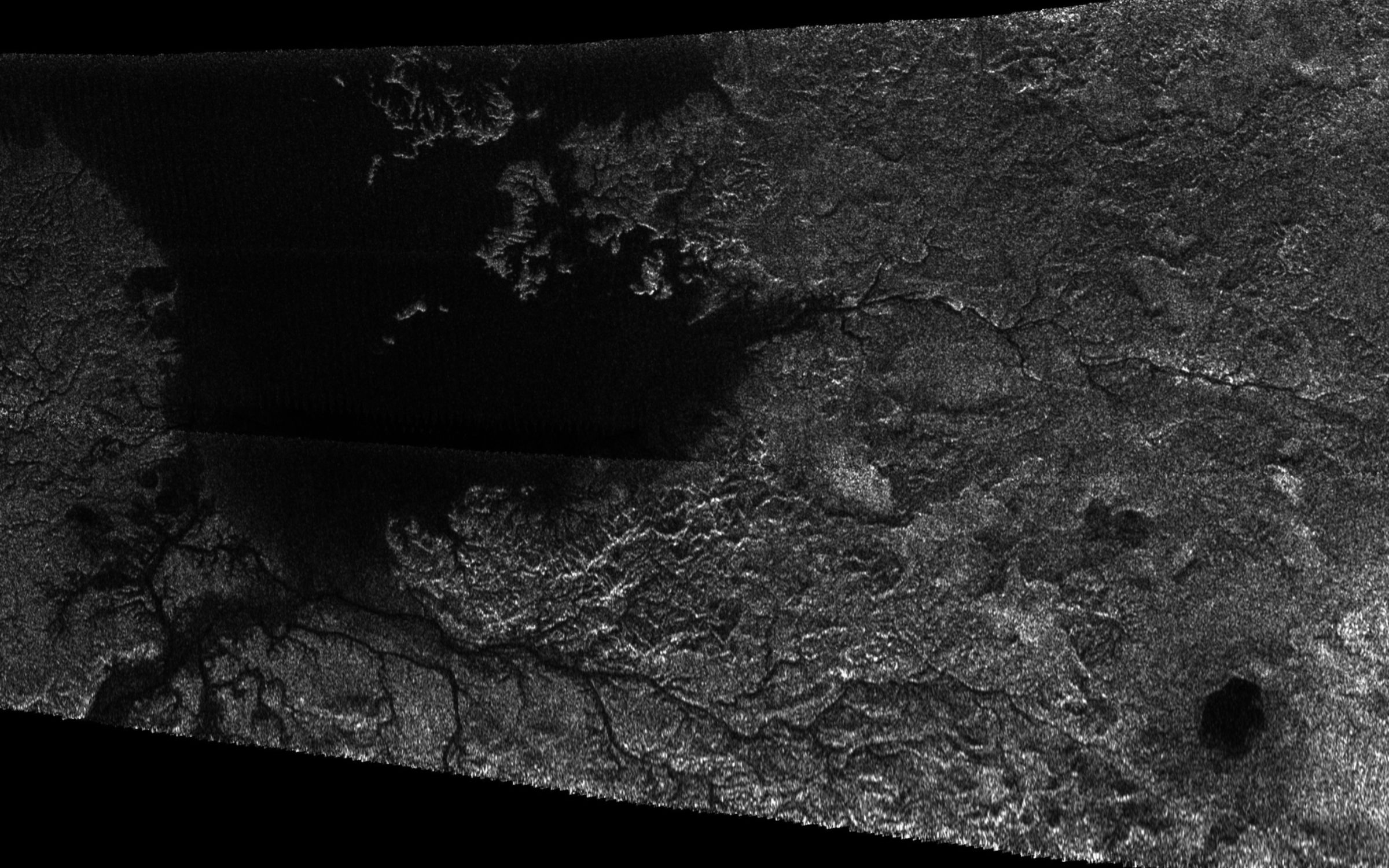

And consider also this photo, a radar image of a river system on Titan.

Clearly, there are similar physical processes operating to create these landscapes. Rain falls out of the sky and flows downhill, collecting into streams that debouch into rivers and thence into lakes or oceans, whence it evaporates back into the sky. Scientists who study this process on one world have expertise valuable to understanding it on the other. On Earth, we call the study of this cycle (and related processes) hydrology, the study of water. On Titan, there's water present, but it's not running in the rivers; water, in its solid form, is the bedrock. It's methane and ethane that fall from Titan's sky, flow in its rivers, and collect in its oceans. On Pluto, it's theoretically possible that there's a liquid nitrogen cycle, at least during some parts of its year. What can you call a field of study that applies to similar processes of rainfall, runoff, erosion, sapping, and evaporation, in similar landforms of rivers, lakes, seas, and aquifers, when there are different fluids on different planets?

I posed this question on Twitter today and I got a lot of suggestions for neologisms, but that's not going to help me out; I need to call things by names that other people will understand when I use them. (Of these suggestions, my favorite was "humorology," referring not to the modern use as in "something funny" but instead to its original meaning of fluid or juice, as in the four humors of Hippocratic physiology, especially because it was followed by the suggestion of "cryology," not as in the thing we do when we're sad but as in cryo-, meaning icy or cold.) Several people suggested "fluid dynamics," but there's already a field of study called that, and it covers how things flow but now how they pool or evaporate or tumble rocks in streams to make them rounded or do all these other things.

Nearly every scientist who answered my question said that really it is "hydrology" that's in common use, even for these non-watery fluids. There are precedents of course. Although some people do talk about "selenology" and "areology" to refer to the physical histories and surface processes on the Moon and Mars, nearly everyone just uses the catch-all term of "geology" despite the fact that "geo" refers to "Earth." Using "hydrology" would make me feel less bad about also using "aquifer" when I'm talking about liquid methane flowing through Titanian sands or liquid nitrogen flowing under Pluto or Triton ices. But if we ever find a place where liquid rock occupies a similar role -- on an exoplanet, maybe, or on a slightly hotter Venus -- I wonder if we'd balk at calling the study of that "hydrology"?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth