Emily Lakdawalla • Jan 23, 2012

Is there life on Venus? Not in reprocessed Venera-13 images.

At the end of last week, a rather sensational article appeared in both the Russian- and English-language sites of the Russian news agency, RIA Novosti. "Life Spotted on Venus - Russian Scientist," ran the English headline; a Google translation of the Russian one goes: "The Soviet probes may have photographed creatures on Venus." Accompanying the article are photos from the Venera-13 lander, one blown up to a rather ridiculous extent, with a blob circled, labeled "Scorpion."

The story is so obviously ridiculous that I would ordinarily not give it a second thought. But one thing gave me pause, and that's the author. Leonid Ksanfomaliti is a senior statesman of Russian planetary science. In addition to his scientific and technical contributions, he is also a popularizer, a speaker and writer who brings space science to the public.

For all this, he deserves enough respect for me to give his published paper the same careful attention that I would to any other paper. I'm grateful to Olga Dobrovidova and Ilya Ferapontov at RIA Science for sharing with me a copy of his paper. It's in Russian, but after spending rather too long feeding paragraphs into Google Translate, I've come up with what seems like a reasonably sensible English translation. Out of respect for copyright I can't reproduce that text here, but I'll paraphrase.

The motivation for the present work, he says, is the recent discovery of more than 500 exoplanets, most of which are "hot Jupiters." These discoveries encouraged him to question whether we are being "terrestrial chauvinists" in assuming that life can exist only under Earth-like conditions. Hot-Jupiter-like conditions prevail, he said, on our neighboring planet Venus, so if one accepts the hypothesis that life might exist under such extreme conditions, then we shouldn't assume Venus lacks it. Therefore, he has chosen to re-examine the data from Russia's successful Venus landers to see if there is any evidence of life.

Before I continue, let's review briefly this decade of Venus exploration. Beginning with Venera 8, in 1972, the Soviet Union landed successfully on Venus nine times. All but the first of the Venera landers was accompanied by an orbiter for data relay. In most cases, the landers were still functioning when the orbiters passed out of range. The orbiters also performed their own remote sensing science. There's a detailed history and summary of the science results of these missions on Don Mitchell's website, in two parts (Venera-8 through -10 and Venera-11 through -14). Although the last Venera landing was 30 years ago, in 1982, the data from these missions continue to be the only "ground truth" we have for all the orbital, flyby, and Earth-based exploration that's been done since. Following the seven Venera landers, two Vega balloon probes landed in 1985, on the night side of Venus, after floating downward for nearly two days.

| Mission | Panoramic Photos? | Launched | Landed | Surface Lifetime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venera 8 | no | March 27, 1972 | July 22, 1972 | 50 min |

| Venera 9 | yes | June 8, 1975 | October 22, 1975 | 53 min |

| Venera 10 | yes | June 14, 1975 | October 25, 1975 | 65 min |

| Venera 11 | no | September 9, 1978 | December 25, 1978 | 95 min |

| Venera 12 | no | September 14, 1978 | December 21, 1978 | 110 min |

| Venera 13 | yes | October 30, 1981 | March 1, 1982 | 127 min |

| Venera 14 | yes | November 4, 1981 | March 5, 1982 | 57 min |

| Vega 1 | no | December 15, 1984 | June 11, 1985 | 20 min |

| Vega 2 | no | December 21, 1984 | June 15, 1985 | 20 min |

Getting back to Ksanfomaliti's article. He says that it is worth re-examining the Venera lander images in particular. His reasoning: to date, most analyses of the photos have been based on a single panorama from each site. These published panoramas are, in fact, mosaics. Most of the landers took and transmitted several photos with each camera, several back-and-forth swings. All of them suffered from some loss of data to noise or other transmission problems, so the published panoramas are composed of the best parts of each of the panoramas. In the present paper, Ksanfomaliti takes the panoramas separately and examines them to see if there are noticeable changes from one frame to the next. Then, he says, we can attempt to discern whether these changes are related to abiological phenomena (such as wind) or whether they are related to his proposal that the planet is inhabited. Also, he says, by examining their shape, we can distinguish whether they have the "ordinary form of surface detail," or whether they look extraordinary.

This is, for me, where the paper begins to run off the rails. It's an excellent notion to examine successive panoramas to look for surface changes. In fact, it's been done before, and it's clear that surface changes did take place from one panorama to the next. Don Mitchell writes on his website about Venera-13 images: "Two images, taken about an hour apart, show the gradual blowing away of soil on the landing ring of Venera-13. Changes in the quality of illumination appear, becoming less diffuse at some times. This is probably due to the movement of clouds, which would probably cause vague regions of lighter and darker sky as seen from the surface." It's very important to recall that the sites that the Venera landers photographed -- actually, sites photographed by any lander of any planet -- are at least somewhat disturbed by the landing. The Veneras kicked up dust and soil that was redeposited on their flat surfaces, some of which was blown away in the brief period that they transmitted data to the surface.

There's another reason that successive images may look different, and that has to do with how they were transmitted to Earth. They were sent using two different types of modulation of the orbiter's carrier signal. The different types of modulation produced different kinds of noise. It's interesting to compare two of the Venera-13 photos' pixel values, as Don Mitchell has done in the graph below. If the two photos were identical, this graph would contain a single line at a 45-degree angle. Data dropouts result in gaps in this line (the value in one of the two images is zero). If the two photos were identical except for one or two tiny objects that moved, it would be a single line with a couple of very small, localized deviations. What we have instead is two photos that are fundamentally similar (most points cluster near that 45-degree line), but where there is a spread to the 45-degree line, indicating a distribution of pixel values around the expected ones. On top, there are some odd systematic variations in a few spots in the photo. There are, in fact, a lot of differences between the two photos, but it's almost all noise.

With all of these natural and artificial reasons why there may be changes in pixel values from one image to the next, it's hazardous to read too much into small changes of blobby shapes. But that's exactly what Ksanfomaliti goes on to do. There is a bold sentence in the paper that I asked Twitter help in translation, and it reads: "It must be emphasized that in the present work on the processing of the initial images images any retouching, drawing-in, additions to, or adjustment of images was completely ruled out." And he says that the use of Photoshop was "categorically ruled out." Yet he goes on to say that adjustments were, in fact, made. Missing bits of images were filled in with data from other images, contrast and brightness adjusted, and (most strangely), the "Blur" and "sharpen" functions in Microsoft Windows Paint were sometimes employed. These are all fairly standard operations in image processing (except for the use of Windows Paint instead of Photoshop for blur and sharpen filters, which is just odd), but they are most definitely "adjustments" of images, especially that blur and sharpen business. Sharpening, in particular, can have weird effects on noisy images. Here's one of his example images. Over-sharpening of the top image has produced a "ringing" of rocks in the bottom image, and a large area of missing data has been filled in with a piece from another image.

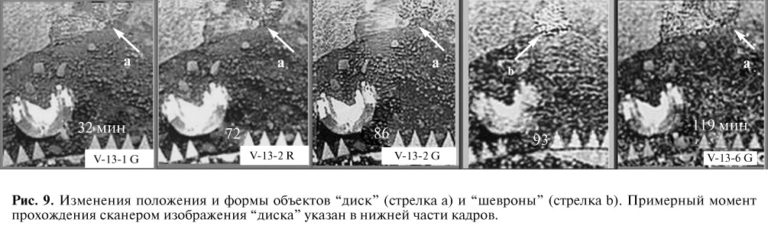

And here's another figure from the paper, showing the areas in which he saw a "disk" that resembles "a giant shell" (a), and an appearing and disappearing set of "chevrons" (b).

And here, I think, is where I am going to stop my analysis. There is so much variation in noise among these five images, and they have been so processed with sharpening and infilling of data, that I think it is pointless to micro-analyze tiny little features and whether they have changed, much less whether they represent the presence of moving, living creatures or not. These images are much less convincing even than those of the Mars Sasquatch.

It's surprising that someone so otherwise respectable can publish something so patently off the wall. As I've chatted with people, various explanations have come up. One person told me that Ksanfomaliti has always had a penchant for things slightly on the edge of reality. Another suggests that thirty years of poring over old data sets, with no successful planetary missions producing new data sets, would make anyone crazy. As for me, I've seen before when successful people become so convinced that they are smart and right that they go over some edge and suddenly think that any crazy idea that flits into their head must be right, because they thought it and they're always right, right? There's no way for me to know what's made Ksanfomaliti make so much out of absolutely nothing. All I know is, there's nothing here. Move along.

And let's send another mission to land on Venus so we can finally get some new data already! Or maybe a long-lived Venus balloon!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth