Jason Davis • Dec 16, 2011

Expedition 30, SpaceX and Stratolaunch

For many folks around the world, the holiday season means spending time time with friends and family. It may seem like a lonely time to be an astronaut or cosmonaut isolated in the International Space Station, 400 kilometers above the Earth's surface. However, as NASA astronaut Dan Burbank explains in his holiday greeting video, that's actually not the case. Burbank says he and his two Russian colleagues have hung decorations and cards, and plan to celebrate with a traditional holiday feast. The trio will also be laying out the proverbial welcome mat as they get ready to play host to holiday visitors.

The crew of Expedition 30 will double in size to six on December 23, when Soyuz TMA-03M docks with the International Space Station at 5:20 UT (10:20 EST). Commanding the Soyuz will be cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko, joined by European Space Agency astronaut André Kuipers, and NASA flight engineer Don Pettit. Kononenko and Pettit have both been to the ISS for prior extended stays (on Expeditions 17 and 6, respectively); Kuipers visited briefly as a member of the DELTA crew transfer mission in 2004. Their journey begins on December 21 at 13:16 UT (8:16AM EST) atop a Soyuz-FG rocket, which will launch from the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazhakstan.

With the addition of Don Pettit, the ISS will have two astronauts that have been trained to receive SpaceX's Dragon capsule. This will come in handy in February 2012, because SpaceX has been officially given the green light to launch its Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule to the ISS.

If you're skeptical that this will happen, consider yourself forgiven; this is not the first time I've listed a date for the Dragon launch in a blog entry. On July 29, I reported that NASA had tentatively approved a launch date of November 30. Then, on November 13, I said that it was scheduled for December 19, but would likely slip to January. It turns out I wasn't conservative enough, so let's try a third time: the Falcon 9/Dragon is now scheduled to launch on February 7, 2012. That is, pending completion of final NASA reviews.

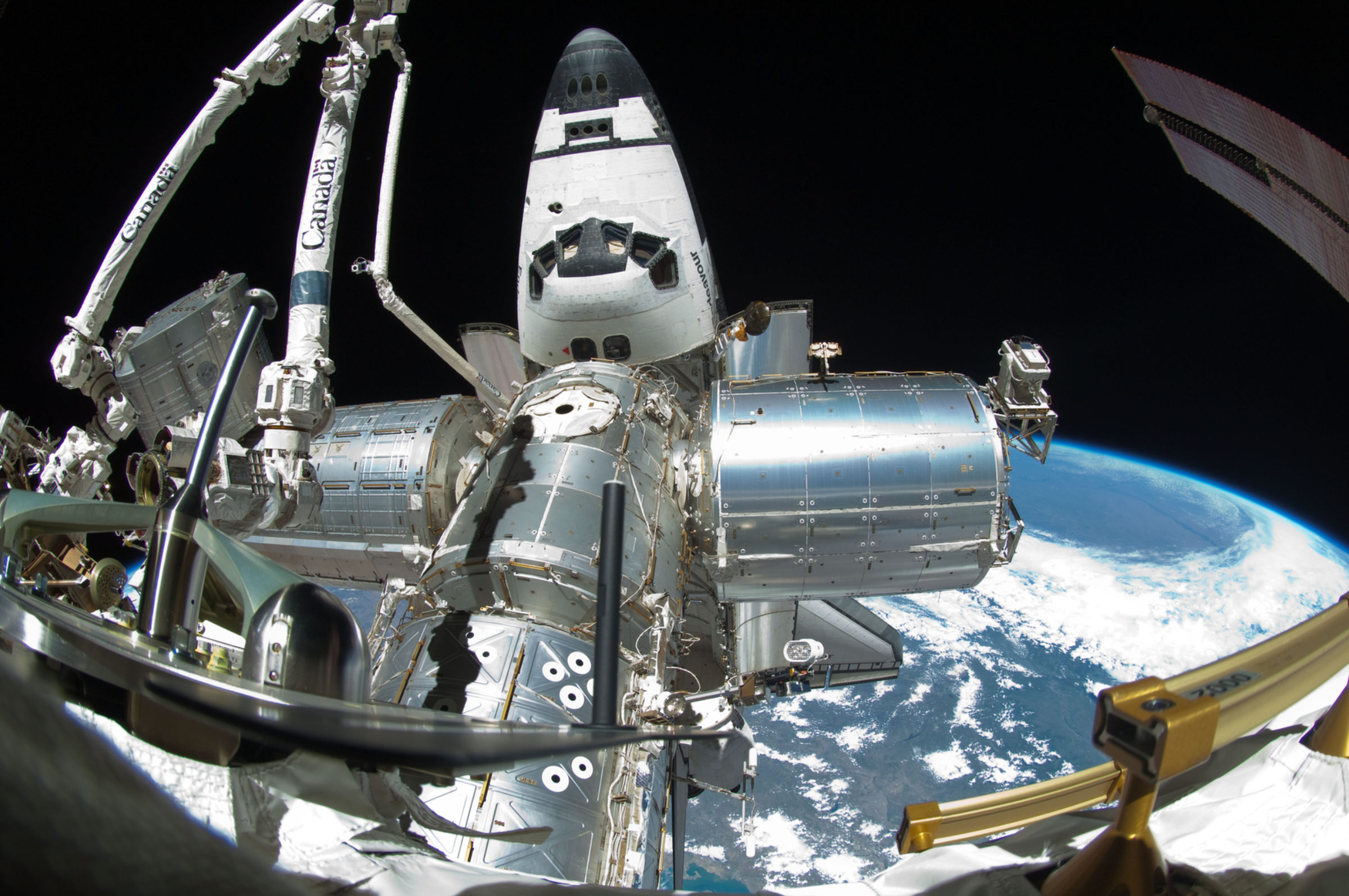

This time, the probability of launch feels a little higher. In NASA's official press release regarding the flight, they list some very specific details about the mission. After the Dragon capsule chases down the ISS, it will hold at a distance of two miles while flight controllers run it through a few shakedown activities. Among these tests is displaying the ability to safely abort a docking should things go awry. If everything checks out, the Dragon will fly close enough to the ISS for Don Pettit and Dan Burbank to grab it with the station's Canadarm2 and guide it to the Harmony node for docking. The pressure between the Dragon and ISS will be equalized, and the capsule's hatch will be opened, revealing a yet-undisclosed quantity of supplies and cargo. The Dragon is scheduled to remain docked to the station for about a week. It will then be loaded with cargo, undocked, and sent back to Earth for splashdown and recovery in the Pacific Ocean.

SpaceX's mission to the ISS will mark a huge milestone for the increasingly crowded private spaceflight industry. That industry has received a plus-one in the form of Stratolaunch, a new venture created by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk (also a current Planetary Society board member), legendary rocket designer Burt Rutan, and Michael Griffin, former head of NASA from 2005-2009. Considering the current field of contenders, what does Stratolaunch intend to do differently?

The company will combine the power of a traditional rocket system with the flexibility of an air-drop vehicle. For comparison, consider Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo, a suborbital space plane. SS2 is designed to be carried to a high altitude and released by a carrier plane. Upon release, SS2 ignites a rocket engine and flies high enough to achieve a few minutes of microgravity, before returning to Earth for a landing on a conventional airplane runway.

Stratolaunch will take that concept a step further, swapping a suborbital space plane for a bona-fide rocket and capsule system. Why would you want to do this? The main reason is flexibility. In the United States, launch facilities are positioned so rockets don't have to travel over populated areas on their way into orbit. Polar-orbiting satellites are typically launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, and traditional low-Earth, East-West orbits require a launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Stratolaunch intends to give their rocket the flexibility to travel about 2100 kilometers (1300 miles) out over the ocean before launch, allowing it to head in virtually any direction. Presumably, the idea is to reduce costs and complexity.

The logistics of such a system are daunting. First, there's the matter of the carrier plane, which would be the largest aircraft ever built, making use of six 747 jet engines and a wingspan larger than an American football field. Takeoffs and landings would require 3.7 kilometers of runway (12,000 feet). Furthermore, liquid-fueled rockets require considerable ground support for pressurizing cryogenic propellants up until launch. Stratolaunch has selected the company Dynetics for the technical integration and mating of the two vehicles.

Although Paul Allen might not care for this comparison, I was curious to see how many times it has been made: a Google search for "Stratolaunch + Spruce Goose" returned nearly 5,000 results. Here's a promotional video of the Stratolaunch concept in action.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth