Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 08, 2011

Notes on Dawn at Vesta from the 2011 American Geophysical Union meeting

Vesta is proving tricky to interpret. Dawn has been there for only a few months, and the data gathered so far has already disproven a number of preconceived notions and generated dozens of new puzzles. Fortunately, scientists love puzzles! But Vesta's puzzling qualities, combined with the rigors of keeping up with a mission in the middle of orbital operations, make for slower going on the science front than we spectators might like. At the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco on Monday, Vishnu Reddy summed up the challenge: "In geology, one of the simplest tools that we have at our disposal is comparison," that is, comparing something new to other things we've studied in the past. "Is there anything else we can compare Vesta to? The answer is no."

There was a Dawn press briefing Monday, followed by a full day of Dawn talks on Tuesday, followed by poster sessions on Wednesday. I couldn't stay for the poster sessions but took a bunch of notes on press briefing and talks. There was not a lot of news in the press briefing; the biggest piece of news, I think, was the announcement that gravity studies have shown that Vesta is definitely differentiated, with mass concentrated toward the center, like the planets and most of the large moons. This was expected from the different compositions of Vesta's many meteorites. With differentiation, you'd expect there to be volcanism, but so far the search for definitively volcanic features has been fruitless. Upon close inspection, a promising-looking candidate for a volcano, an "unusual dark hill," shows no convincing features of a volcanic origin. The dark splat appears to be a surface deposit. It could be dark material from an impactor, or an impactor could have struck some subterranean dark deposit.

There was slightly more detail in the oral sessions. Vesta has a variety of types and colors of surface features, and everywhere there is evidence of landslides and slumps ("mass movement features," in geologists' lingo). Vesta appears to be especially conducive to landslides because it has high gravity (for an asteroid), locally unusually steep slopes, and a very thick surface layer of broken-up rock ("regolith"), hundreds of meters thick. For comparison, the lunar regolith is estimated to be only a few to ten meters thick.

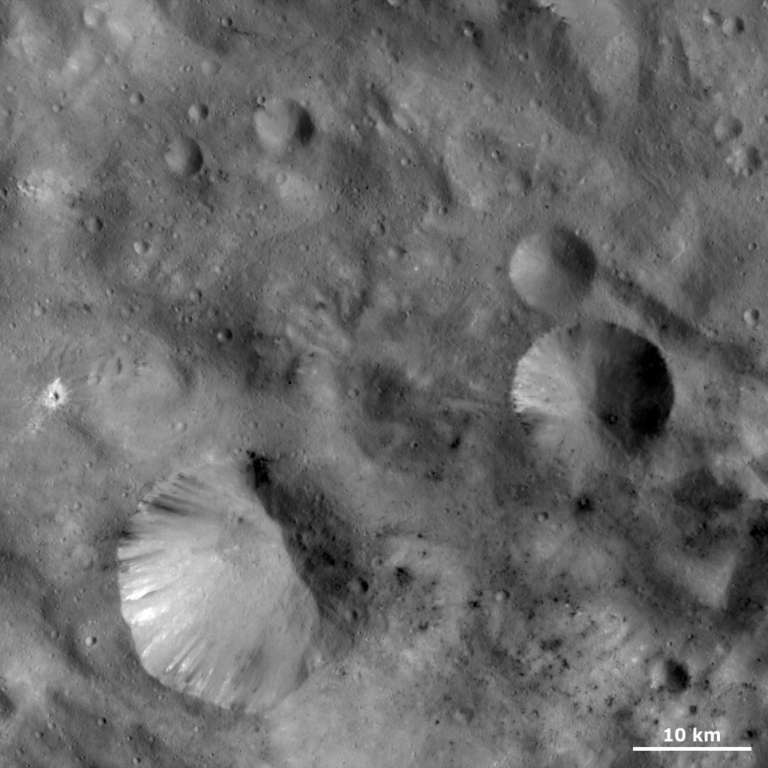

Seen in map view, Vesta's craters are very strangely shaped, Ralf Jaumann said during his talk. Ordinarily, craters are classified according to their state of degradation. Craters with sharp rims and prominent rays are interpreted as fresh. Craters with smoothed rims and erased rays are interpreted as old or degraded. On Vesta, you see a lot of craters that look like this, with partly sharp and partly smooth rims:

What's going on here? With the benefit of topographic information (which I don't have for this particular image), scientists can see that these craters often occur where there are steep slopes. After the crater forms, the upslope wall collapses in a landslide that fills the floor and sometimes even runs out over the downslope rim. On a crater where this has happened, none of the original rim is preserved -- it's all either collapsed or been buried in a landslide.

Probably the most mind-blowing talk was by Eric Asphaug. I've written about the work he and Martin Jutzi have done to perform 3D simulations of the giant impact that produced Vesta's south polar basin. Here's the two relevant videos:

Asphaug summarized the high points: "Vesta's mega-craters grow and collapse on a time scale comparable to its 4-hour rotation, so there are Coriolis effects on the ejecta. Excavation and collapse take about an hour. The Coriolis effect generates vorticity. Is it a stormy crater? Does it generate a maelstrom of flow within the crater?" Unfortunately for Asphaug and Jutzi's model, though, the present topography of the real Vesta does not look very much like the endpoint of their simulation. Asphaug had a sense of humor about this: "There's a sweet spot to modeling asteroids where you have enough data, but not too much data." He earned a chuckle from the audience for that one.

Why don't the models match reality? Asphaug suggested three reasons. He said the target structure may be different than what they modeled -- Vesta may have greater internal strength. The impact was probably a lot less energetic than the one they modeled, now that they know that Vesta's south polar basin is actually two overlapping impact basins. And finally, "we probably did not model the event to completion." Their model goes through the one-hour period of excavation and collapse, but no longer. Asphaug said that Vesta may actually "ring" for hours or even days after such a large impact, with crustal motions that can cause landslides and softening of features that do form. (He called this the "roach motel" model of Vesta's core, crediting Jeff Moore for the conceit: "energy can get in but it can't get out.") Unfortunately, identifying the possible problems doesn't make the modeling task any easier. To map out the range of possible outcomes given the range of possible basin-forming events on the range of possible physical properties for Vesta to even two hours of time after the impact woud require hundreds of simulations and a 128-processor computer running continuously for years. "3D modeling is best used as a tool to test a few key hypotheses," he concluded.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth