Jason Davis • Dec 03, 2011

Curiosity, from a 1935 perspective

On Saturday, November 26 at 10:02 ET (15:02 UT), an Atlas V rocket carrying the Mars Science Laboratory lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The launch was a success -- NASA's next great rover, Curiosity, is coasting gently towards Mars. It will drift through interplanetary space for more than eight months before it enters the final, action-packed phase of its journey, during which it will be lowered by a skycrane maneuver onto the fourth planet in our solar system.

A few hours after the launch, I found myself in an antique store, and happened upon a dusty book titled Astronomy, Third Edition, by John Charles Duncan. Astronomy was published in 1935 -- that's 76 years before Curiosity left the Earth, and 23 prior to the launch of the world's first satellite. The previous owner of the book seems to have been a William Watson Baker, a student using the textbook for a course at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

With images of Curiosity's departure still running through my head, I purchased the book for a mere two dollars and began to flip through the pages for sections on Mars. What would Mr. Duncan think of the gently spinning backshell of Curiosity I saw earlier, separating from its Centaur booster as it departed from Earth orbit? How would he react to the scientific discoveries that have already been made about Mars, and those yet to come from NASA's automobile-sized rover?

I was amazed, not only by what Astronomy gets wrong, but also by what it gets right. In 1935, we were starting to develop a pretty firm grasp on our place in the solar system, and by extension, the universe. Clyde Tombaugh had discovered Pluto five years earlier. Edwin Hubble had recently proved that strange phenomena like the Great Andromeda Nebula weren't really nebulae at all, but wholly separate galaxies from our own. So where does Astronomy stand on the topic of Mars?

For one thing, it's correct about Mars' atmosphere on several counts: "Although Mars certainly possesses an atmosphere, it is probably of low density as compared with our air." Notice the language: "certainly" possesses an atmosphere, "probably" of low density. What led to this conclusion? "The existence of an atmosphere on Mars is proved beyond a doubt by the occasional presence of floating clouds and the melting and re-forming of the polar caps." Astronomers were positive there was an atmosphere, but less certain on how dense it was. Astronomy lists a handful of conflicting spectrograph measurements that place Mars' oxygen levels anywhere from 25 to 0.1 percent of Earth's (the latter being more similar to the now-accepted value of roughly 0.01 percent Earth's).

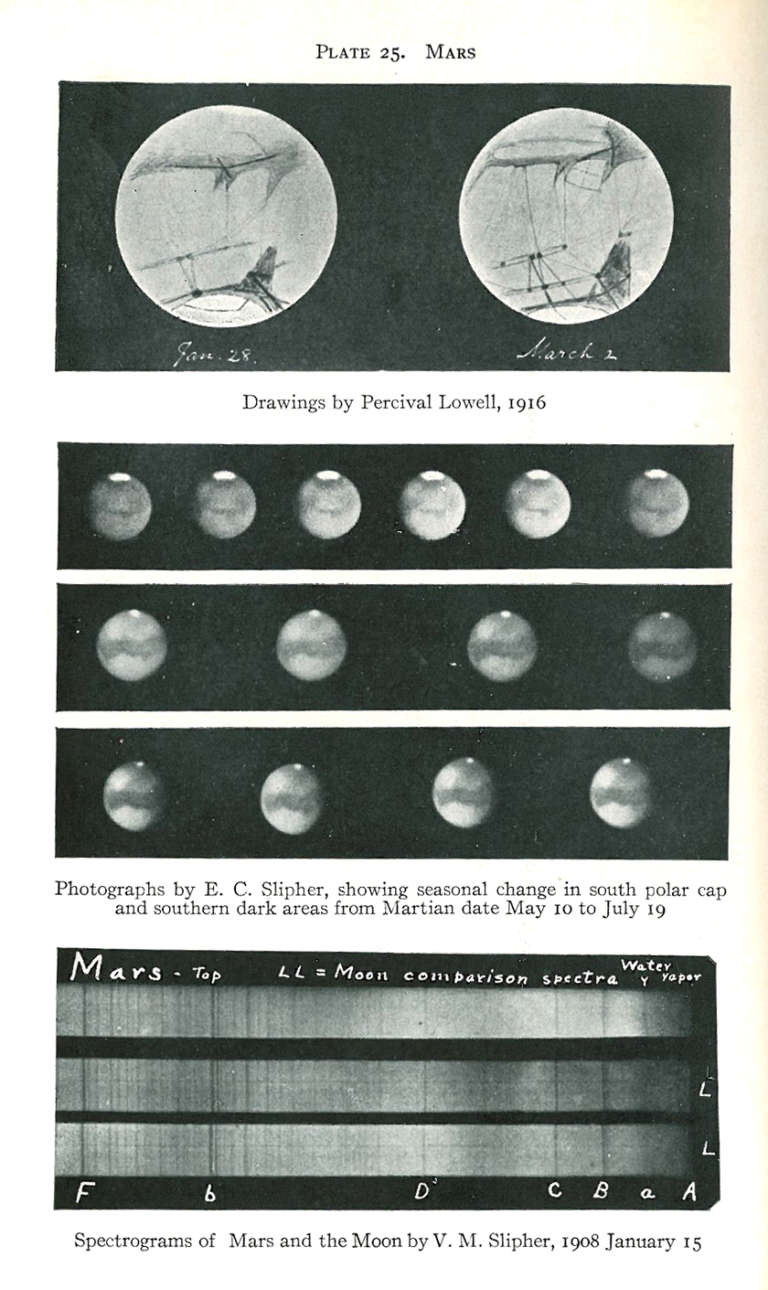

When interpreting visual observations, Astronomy highlights how much uncertainty there was in 1935 on the subject of life on Mars: "..yet the seasonal changes of the dark areas are best interpreted as due to vegetation, and where vegetation flourishes, at least on the Earth, animal life is likely to exist also." Oops. Clearly, the observed darkening and lightening of various sections of Mars with respect to its seasons were a topic of much speculation. "These changes are very suggestive of the vernal quickening and autumnal fading of vegetation."

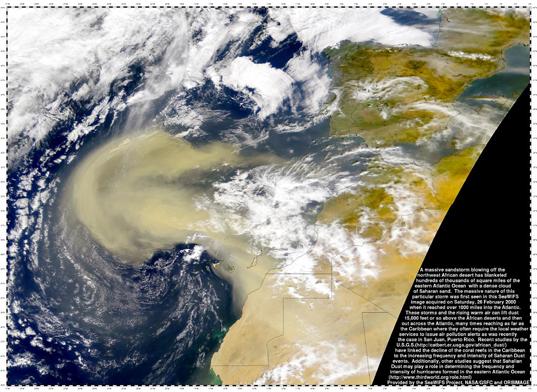

Regrettably, it turns out Mars isn't the kind of place one goes for a drive to watch the leaves change. But can you blame astronomers of the time? Check out this page from the book, which shows what they were working with in terms of visual observations:

There ended up being a more mundane explanation for seasonal color changes on Mars: dust storms. However, it's easy to see why a little imagination turned this phenomenon into seasonal vegetative changes. Check out this picture of a dust storm on our own planet, when viewed from space:

One theory about life on Mars that the book debunks is the famous Martian "canali," first noted by Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. "Canali" literally translates to "channels," but was mistranslated to canals, and the notion that the lines crisscrossing the Martian surface might be irrigation ducts created by extraterrestrials was born. The biggest proponent of this idea was the quirky astronomer Percival Lowell: "Lowell observed Mars assiduously at every opposition from the time of the founding of his observatory [in Flagstaff, Arizona] until his death in 1916, and his works have been supplemented by that of other members of his staff."

It would later be shown that the "canals" observed by Schiaparelli and others were optical illusions caused by the limited telescopic equipment of the time. However, at the time of Astronomy, the only hard evidence against the canals' existence were that they seemed to exist on both the "seas" of Mars (the lighter areas) as well as the "continents" (the darker areas). This cast serious doubt on their alleged purpose as irrigation ducts.

It's interesting that Duncan gives so much page time to Lowell and the canals. Reading through the book's section on Mars gave me the impression that Duncan, out of respect for the deceased astronomer, was trying to let him down easy. The science against the thriving existence of life on Mars was starting to pile up, but astronomers of the time seemed to be a little melancholy when releasing their conclusions.

Can you blame them? 76 years later, we are still seeking answers when it comes to the question of life on Mars. Curiosity is the latest tool in that scientific quest to see if we are alone in the universe. One can't help but wonder what our 2011 astronomy textbooks will look like when they're pulled from a dusty shelf by future generations.

Note from Emily: I wrote about a similar experience finding an old photographic astronomy text in a used bookstore when I discovered Mars by Earl Slipher.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth