Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 21, 2011

Curiosity in context: Not exactly "Viking on wheels," but close

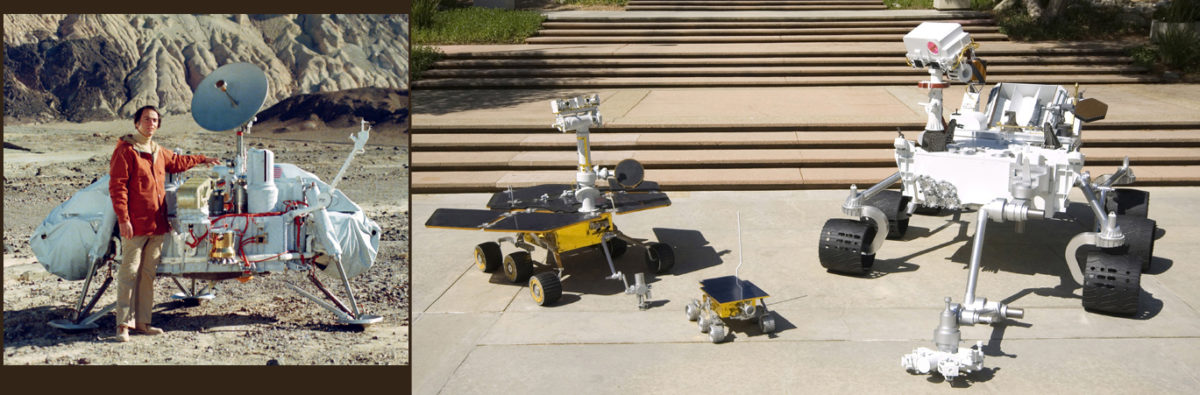

As I was beginning my research for my two magazine articles on the Curiosity rover's upcoming mission to Mars, I needed to figure out for myself how exactly this gigantic, ungainly machine fit in to the context of past Martian missions. Clearly, Curiosity was bigger than Spirit or Opportunity and much bigger than Sojourner. That's no great insight; JPL published a "rover family portrait" that nicely summarizes the way JPL's rovers have grown and changed from the teeny Sojourner to the graceful, human-scale Mars Exploration Rover, to the nuke-powered Curiosity.

But how much bigger, and why? One of the first things I did was to put together a table of the three rovers, comparing their masses, their instrument payloads, and so on. It was clear from the table that Curiosity is as big as she is because she's hauling around an instrument package 100 times the sizeof Sojourner's, and a still-impressive 13 times the size of Opportunity's. This is so outrageously oversized compared to past missions that I needed to find some other context. A bit of web searching made me realize that there has been something with such a huge and (for its time) complex payload sent to Mars before: the Viking landers. Here's my comparison table, among the three rovers and the Vikings. I wondered: is Curiosity really just Viking on wheels?

| Sojourner | Spirit and Opportunity | Curiosity | Viking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass of rover (kg) | 10.6 | 185 | 900 | 576 |

| Mass of science instruments (kg) | 0.75 | 5.5 | 72 | 91 |

| # of science instruments* | 1 | 5 | 10 | 8 |

| # of engineering cameras | 3 | 6 | 12(6 with full redundancy) | 0 |

| Mission goal | To demonstrate technology, and determine the elemental abundances of surface rock. | To determine the history of climate and water at a site on Mars where conditions may once have been favorable to life. | To explore and quantitatively assess Mars as a potential habitat for life, past or present. | To conduct a detailed scientific investigation of Mars, including a search for life. |

| Wheelbase | 65 cm long, 45 cm wide | 141 cm long, 122 cm wide | 280 cm long and wide | 3 equally spaced footpads 221 cm apart |

| Wheel diameter | 13 cm | 26 cm | 50 cm | -- |

| Camera height | 26 cm | 152 cm | 200 cm | 130 cm |

| Energy per sol (avg.) | 100 W-hr (solar array) | 900 W-hr (solar array) | 2400 W-hr (RTG) | 1600 Wh per sol (RTG) |

| Nominal mission | 7 sols / a few m traverse | 90 sols / 600-1,000 m traverse | 687 sols / 20,000 m traverse | 45 sols |

| Actual mission | 81 sols / 100 m traverse | Spirit: 2,210 sols (at least) / 7,730 m traverse pportunity: 2,500+ sols and 27,000+ m traverse and counting | ???? | Lander 1: 2,245 sols ander 2: 1,281 sols |

| *instrument totals do not include cameras used for engineering purposes such as hazard avoidance, nor do they include instrument positioning tools like camera masts, robotic arms, or sampling equipment. | ||||

When I interviewed Matt Golombek (who led the selection of Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity's landing sites and who was the principal investigator on the Pathfinder mission, which carried Sojourner to Mars) I asked him whether one can get away with calling Curiosity "Viking on wheels?"

Matt said it wasn't a bad characterization but that there were a few really dramatic differences. Curiosity, like Viking, carries a tremendously capable analytical laboratory suite. These are instruments where you grab a sample from out in the Martian environment and bring it inside the spacecraft into a controlled environment. In that controlled environment, you can run a number of experiments on these selected samples. As with Viking, most of Curiosity's payload resides in these sophisticated analytical laboratory instruments. So a significant amount of time on the mission will be devoted not to driving, but rather to identifying, collecting, preparing, delivering, and analyzing samples. Remember the arduous challenges of obtaining and delivering samples on Phoenix? Curiosity's sample collection and delivery will hopefully go better than Phoenix' did, but it probably won't go much faster.

The main difference between Curiosity and Viking instrument suites reside in the questions they were seeking to answer. The Viking landers were sent to Mars with the overarching question: is there life on Mars? Unfortunately, the answers were equivocal. Matt assured me that the Mars program learned a lesson well from Viking. The question that Curiosity is seeking to answer is: was or is Mars a place that had the conditions necessary to support life? The reason that this is a better question is that we will learn a great deal about Mars even if the answer to this question winds up being equivocal. The Vikings went to Mars to search for life and didn't find it. What does that mean? Is there no life on Mars? Was there once, but there isn't now? Is there or was there life, but we just looked in the wrong place or in the wrong way?

"In a sense," Matt told me, "We swung for the fences, and we struck out. You spent most of your money on a negative result. Okay, we learned a little bit about the chemistry and mineralogy of the soil (more chemistry than mineralogy), but that isn't what you spent all that money to do."

Curiosity's instruments aren't out to detect life. They are out to describe Mars' environment, past and present, in greater detail than ever before, much more so than was possible with Spirit and Opportunity's instrument suites. "The major difference for us geologists," Matt said, "is that we'll get dramatically more definitive chemistry and mineralogy. On MER we kind of infer mineralogy from Mini-TES and Moessbauer. But that's becoming difficult now that the Mini-TES isn't working anymore, and the Moesbbauer takes so long to get spectra that we don't use it very much. When you put something in an XRD and XRF" (these are the complex analytical tools in Curiosity, the instruments called CheMin and SAM), "you get incredibly detailed information about the mineral structure, as well as the geochemistry about what's in those minerals, far beyond what we've gotten from any mission sent to Mars. Far, far beyond.

"MSL's going to look at the same materials we've seen with all the other Mars missions with some fresh instruments. It won't matter whether we find phyllosilicates or not, we're going to learn a huge amount about the materials. if you know what the minerals are and the layers are, you know what the environment was. That's the most compelling part -- we don't know whether [prebiotic chemistry] ever began on Mars; it's kind of a needle in a haystack search, and you don't want to only do that. You want to get all that basic information, what the environment was, was it conducive to life, and were the building blocks for organic materials available. We'll answer those questions regardless of whether there's actually organics. If we find them, it's a great bonus. But if we don't, that's okay too, we've still made a major step forward."

I'll be explaining Curiosity's instrument suite in more detail tomorrow. But today, I'll leave you with this picture. Curiosity is clearly descended from JPL's past six-wheeled, insect-legged, mast-camera'd, robotic-armed rovers. But its scientific roots go all the way back to those first footpads that ever touched down on the Red planet. Curiosity truly represents the culmination of a campaign that NASA has (almost) relentlessly pursued for the last 36 years.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth