Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 21, 2011

Keeping track of UARS' reentry

Unless you've been living under a rock you've probably heard that a very large Earth-orbiting satellite is going to be reentering Earth's atmosphere soon, and there's a small but nonzero chance of debris coming down where somebody might actually find it. The chance is smaller, but still nonzero, that something or someone will get hit by a piece. The odds of any one person getting hit by a piece are somewhere around 1 in 20 million million.* The actual date and location of its fall has been very uncertain because it depends upon qualities of the upper atmosphere that are themselves influenced by highly variable solar weather. As time gets shorter, predictions get a little more certain, so we now know for sure that Friday is the day. (Depending, of course, on your time zone.)

Here's a roundup of some useful facts and links that you can use to learn about and follow UARS' demise. One of the most surprising facts that I encountered is worth mentioning here at the top: even just two hours before reentry, the uncertainty of reentry time is on average ± 25 minutes for circular orbits, which equates to ± 12,000 kilometers on Earth, or roughly half its orbit! So we'll know for certain the ground track along which it will come down, but even two hours before impact we'll only be able to predict on which half of that orbit it'll reenter.

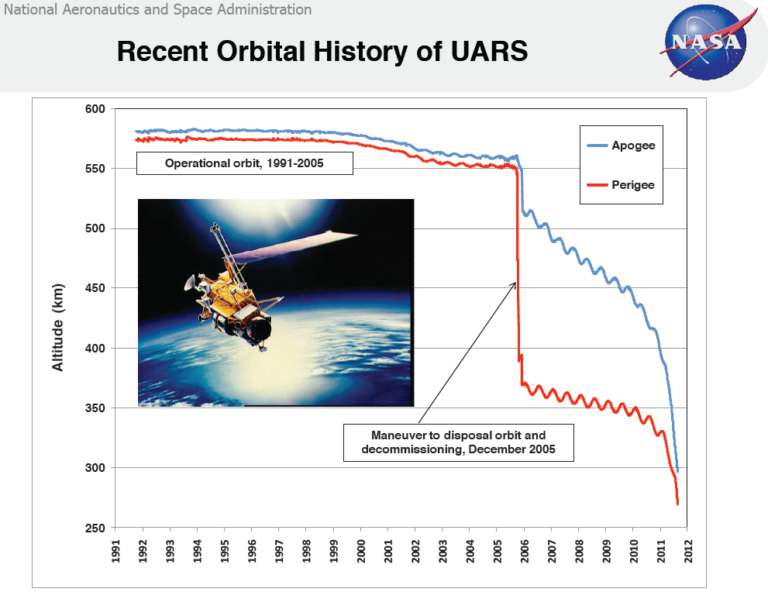

UARS, or the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite was launched in 1991. It initially orbited at about 580 kilometers altitude. It weighs nearly 6000 kilograms and is about 11 meters long by 5 meters wide. It has a single solar panel 1.5 by 3.3 meters in size. It was officially decommissioned on December 14, 2005 after being moved to a lower, elliptical "disposal orbit" with a perigee of about 370 kilometers and an apogee above 500 kilometers. It experiences drag as it encounters the uppermost atmosphere at the lowest point of its orbit, which reduces its orbital energy, thus shrinking the orbit. The apogee has been lowering faster than the perigee. But now it is feeling atmospheric drag throughout its orbit, so the orbit is decaying very fast. When solar activity picks up, as it has in the last few days, the upper atmosphere is heated and swells up, speeding the decay of UARS' orbit.

As of 10:04 UTC today, its orbit was nearly circular and only 195 by 209 kilometers in altitude. One good place to get a current view of its orbit and ground track is heavens-above.com.

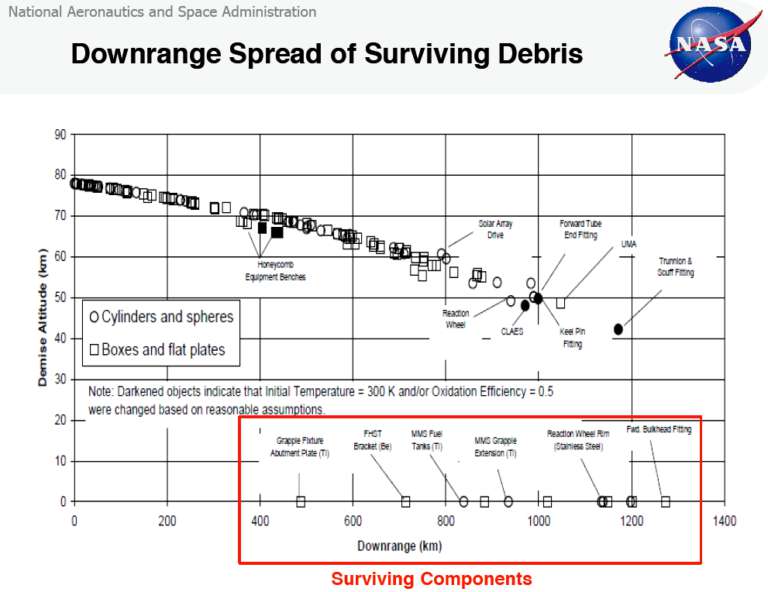

NASA defines 122 kilometers for re-entry altitude, the altitude at which shuttles must switch from steering with thrusters to maneuvering as an airplane. Once UARS descends to this altitude, it will fall very fast. According to the NASA Orbital Debris Program Office, solar arrays usually break off the spacecraft at an altitude of about 95 to 90 kilometers; the rest of the spacecraft breaks up at between 84 and 72 kilometers, when aerodynamic forces exceed the spacecraft's structural strength. Components made of low-melting-point materials (like aluminum) burn up at altitude, while components made of higher-melting-point materials (like titanium, steel, and carbon-fiber) survive longer. If an object is contained inside a housing, the housing must burn up before the interior receives significant heating.

The following information is from NASA's UARS reentry website and especially this risk assessment presentation (PDF)

The orbit is inclined 57 degrees to the equator. Thus its ground track covers a zone from 57 south to 57 north latitude.

Official updates on the impact location prediction will be prepared and released to the public at the following intervals: impact minus 2 days, minus 1 day, minus 12 hours, minus 6 hours, and minus 2 hours. However, even just two hours before reentry, the uncertainty of reentry time is on average ± 25 minutes for circular orbits, which equates to ± 12,000 kilometers on Earth, or roughly half its orbit.

There are 26 components of UARS that are predicted to fall to the ground, amounting to 532 kilograms of material. This debris will be scattered in a narrow zone along its orbital track that's a bit under 1000 kilometers long.

The estimated human casualty risk is 1 in 3200. What this means is that there is a 1 in 3200 chance that one person on Earth will be hit by falling material. Assuming a population of 7 billion, that means there is a 1 in 22,400,000,000,000 chance of YOU being struck by falling material. As the predictions improve, we'll know better on what orbit the spacecraft will come down, which will narrow the region of hazard to a much, much smaller area, increasing the risk for a few but making it zero for everyone else.

It's now very close and moving very fast. It's bright enough to be visible to the naked eye where it happens to pass nearly overhead near sunset or sunrise, but hard to spot because of its speed and the uncertainty in its position. Here's an amazing video shot by Thierry Legault, which I first saw on Universe Today, in which you can clearly make out the shape of the spacecraft and its solar panel and its tumbling motion in the sky:

I probably won't post a blog entry on this again until after it crashes. But I'll certainly be Tweeting updates. Other good follows for UARS updates are @NASA and @UARS_Reentry.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth