Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 10, 2011

Wheels on Cape York!

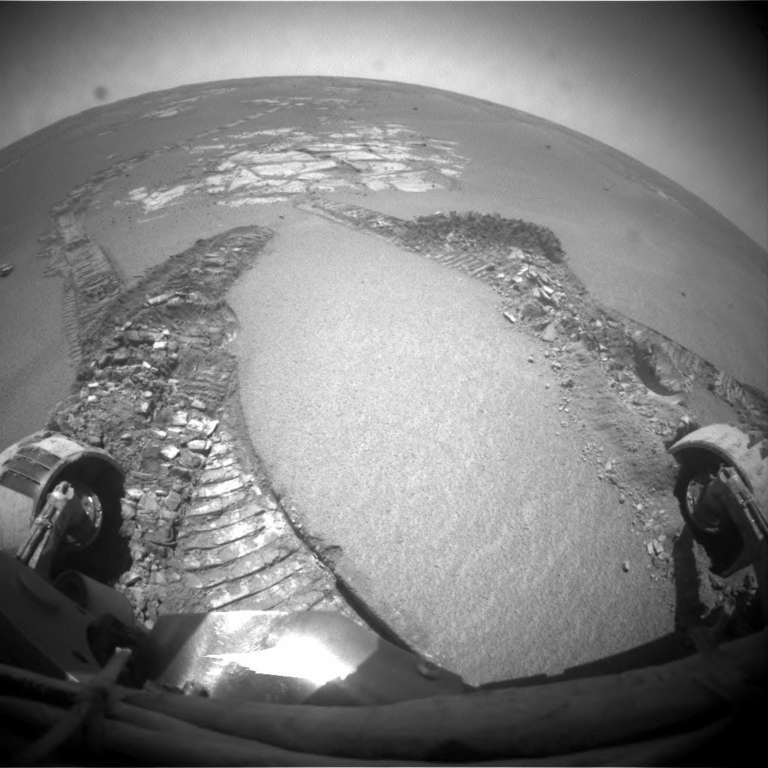

Ever since she landed on Mars, there have been three basic materials under Opportunity's wheels. There's drifty sand (which has sometimes proven to be a hazard):

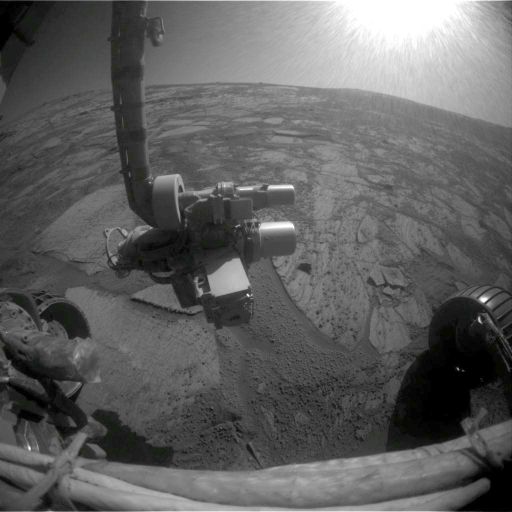

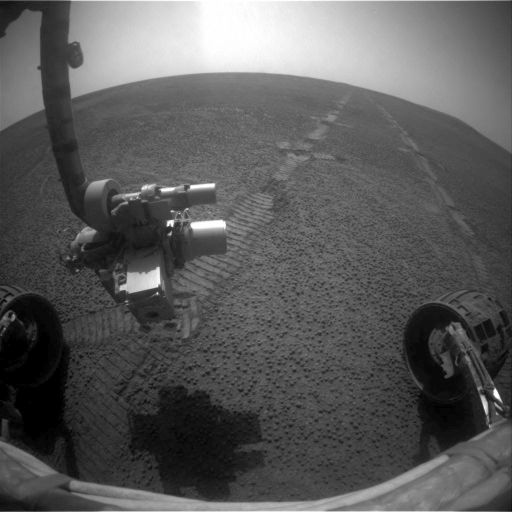

And there's this sulfate-rich rock that has been eroded into flatness by wind acting on it over millions of years:

And there's "blueberries," the hematite-rich concretions whose distinctive chemical signal brought Opportunity to Meridiani Planum in the first place.

The rocks of Cape York do not look the same as what we've seen before. They're finely layered, and that's certainly true of the Meridiani sulfate rocks, but they have a different way of eroding, and there are these odd little bright veins running through them. If I'd been handed this image and told to guess which rover it came from, I'd've said Spirit.

Here's a context map to show you where we are:

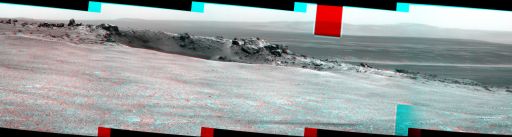

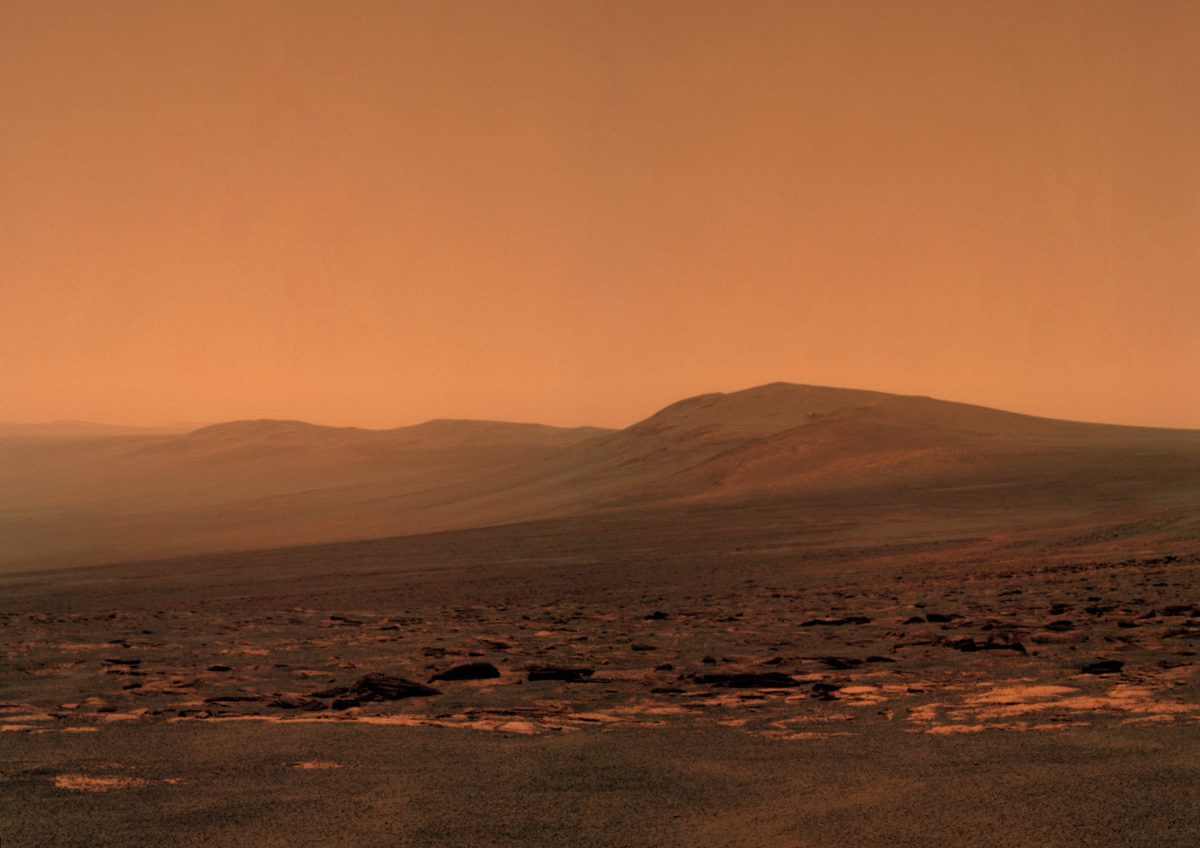

That's not the only thing that's different about Cape York. Check out this view. It's a red-blue anaglyph but it can be appreciated even if you don't have 3D glasses handy.

That is a HUUUGE block on the far rim of Odyssey; it's more than two meters across, bigger than the rover.

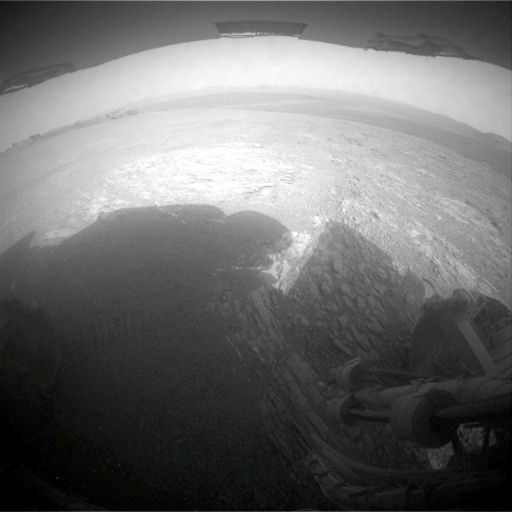

Gorgeous mountain views -- fresh rocks -- it's like Opportunity has landed all over again, and starting a brand new mission.

Except for one problem. Opportunity's science package is seven years past its warranty. A few of her science instruments are working just fine; these include the Panoramic Cameras, the Microscopic Imager, and the Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer. (There is dust coating the front of the Pancam optics, but when necessary for science they can compensate by using a slice in the center of the images where the dust is not as bad.) Also, due to the soft nature of Meridiani's rocks, the Rock Abrasion Tool's grinding wheel is still in good shape, though the brush is bent so it doesn't do a great job of cleaning off rocks. The shoulder joint of the robotic arm is frozen, so the arm can only reach a skinny area right in front of it, but the drivers have gotten very good at positioning Opportunity where she can use her arm, so she's still very effective with the arm-mounted tools.

But there are two critical pieces of Opportunity's science package where the state of things is not so good. Opportunity's Mini-TES instrument -- the one that allows the rover to identify minerals from a distance -- is hopelessly contaminated with dust that blew into the instrument's periscope during the horrible dust storm in 2007. And the Mössbauer spectrometer, which allows the rover to identify iron-bearing minerals in the rocks right in front of it, is very weak. The radioactive cobalt source that it uses to generate gamma rays has a half-life of only 271 days. Opportunity has been on Mars for 2760 Earth days, more than 10 half-lives. So the source is only 1/2^10 or 1/1024 as strong as it was when Opportunity landed; put another way, it would take more than a thousand times as long for Opportunity's Mössbauer to get the same quality measurement as it did when the rover landed (if I understand the instrument right; if I haven't I'm sure I'll be corrected in the comments). But without the Mini-TES, the Mössbauer is the only tool Opportunity has to determine the mineralogy of the rocks she's examining. And since mineralogy is what brought Opportunity here, I am guessing that we are in for some very, very long periods where Opportunity holds perfectly still with her arm against a rock, patiently waiting for the few remaining atoms of cobalt-57 to make enough gamma rays to tell her what the rock is made of.

But it's not time for that yet. We're still doing initial reconnaissance, and it's a wonderful place to be looking around!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth