Emily Lakdawalla • Jun 20, 2011

Cassini finally catches Helene

The Cassini team has had a wretched time trying to get pictures of Helene in the past, but their streak of bad luck is over. Helene is one of the four "co-orbital" moons in the Saturn system, which occupy metastable spots in the leading and trailing Lagrangian points on the orbits of Tethys and Dione. It's the biggest of the four, but that's not saying much; it's only about 36 by 32 by 30 kilometers across, so it's in the same general size range as Phobos. It's proven challenging to predict where it's going to be with enough accuracy to make sure Cassini can capture it in its camera field of view, with the result that nearly every imaging sequence that Cassini has been commanded to take of Helene has seen the moon wander out of the field of view at one time or another.

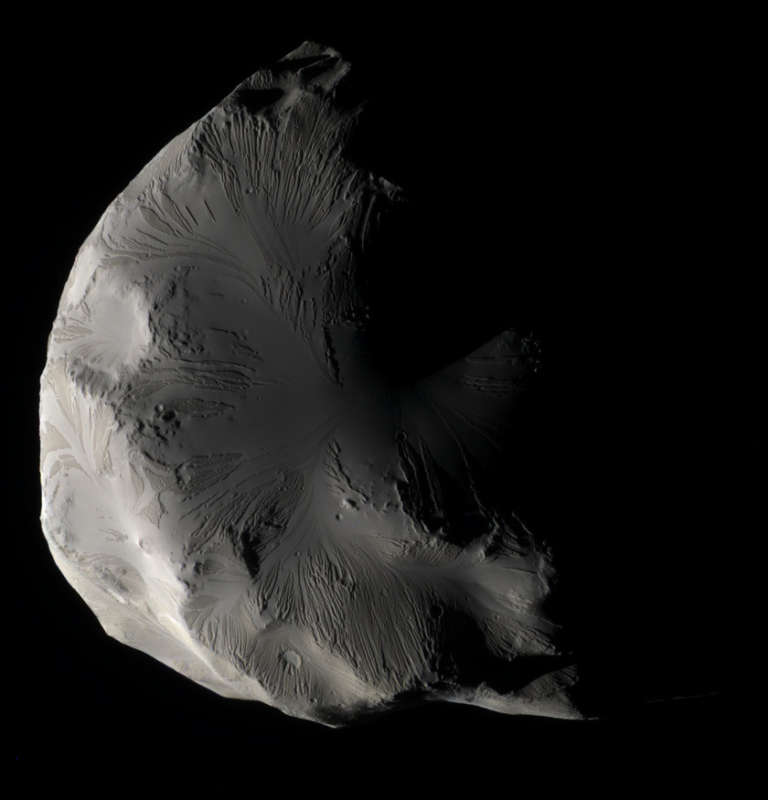

Well, Cassini has finally achieved gorgeous global imaging of Helene with a spectacular flyby on Saturday, in which they absolutely nailed the spacecraft's pointing and got Helene to pose prettily for the camera from beginning to end of the encounter. And what a wacky, wacky world Cassini has revealed Helene to be!!

We saw these gullies on the previous close flyby but this is a much better view. There are two things that are very strange about these gullies. One is to see them at all. Features like this, if seen on Earth or even Mars, would be assumed to have something to do with water, but there is no possibility of liquid water on Helene (though it is likely made mostly of rock-hard water ice). These gullies must form by a dry process in which material -- likely very powdery dusty stuff -- cascades toward local topographic lows.

The other thing that is very strange is the strong difference in color between the higher-standing stuff and the smooth gully slide areas in between them. Others of Saturn's moons have some color variations across their surfaces, but really I don't know of one other than Iapetus where there are such sharp boundaries between one color of material and another. The color differences are most obvious on the right side of the image, where the Sun hits Helene directly and there aren't many cast shadows; color differences fade as you get toward the lower and lower light near the terminator at the left side of the image. Those color differences are what make this movie version of the flyby images appear to "beat" -- every time an image is shot through a short-wavelength ultraviolet filter, the inter-gully ridge areas darken substantially. I'm kind of proud of how this animation turned out -- feel free to share it!

Cassini's June 2011 Helene flyby Cassini got its best-ever view of Saturn's moon Helene on 18 June 2011, when it approached to within 7,000 kilometers. Helene is a co-orbital moon of Dione. The sunlit face is mostly the side of the moon that always faces Saturn, and is covered with strange gully-like features.Video: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI / animation by Emily Lakdawalla

The surface appears to "beat" with contrast changes because Cassini was cycling through different filters to take the images. In short-wavelength filters, the areas between gullies are darker than the smooth gully floors, while there is less contrast between them in the longer-wavelength filters.

To generate this animation, I aligned the frames and rotated them 180 degrees to place north up. Then I used the Photoshop "dust and scratches" filter to remove most of the cosmic ray hits. This also removed a bit of detail from gully areas, unfortunately, but it saved me a lot of time and effort. I cleaned up the worst remaining cosmic ray hits using the clone tool. I adjusted the contrast to push black space to completely black and to bring out some more detail in shadowed areas.

As you watch the animation, try focusing on different areas. Like the massive crater in the north that is partially illuminated in the opening of the animation. Or the faceted shape of the moon, which suddenly brings a huge sunlit face into view. Also try to see if you can see the shadows move across Helene's face as it rotates; most of the apparent motion is due to Cassini's motion, but some is Helene rotating on its axis.

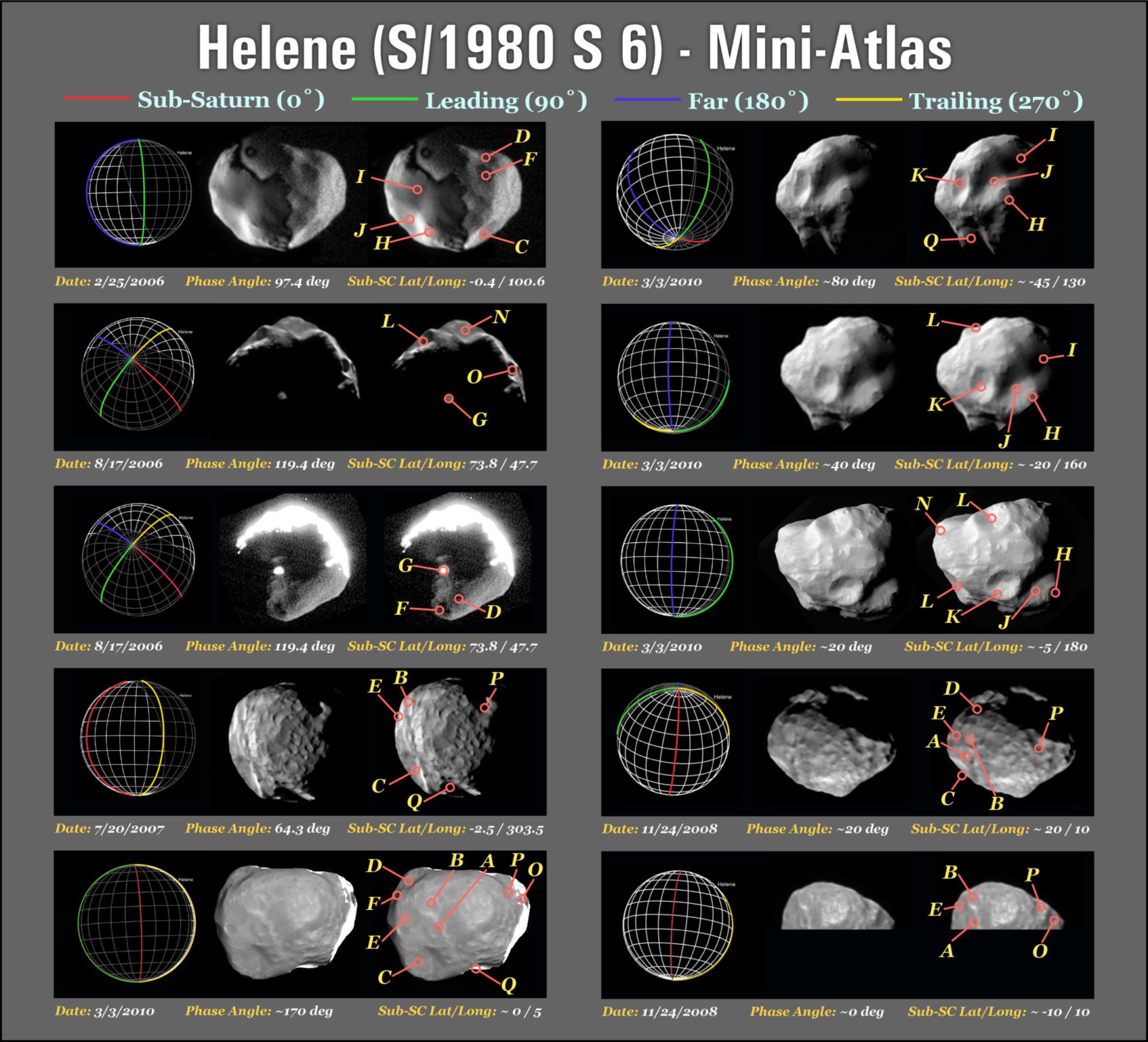

There are a couple of dozen little tiny bowl-shaped impact craters scattered across the image, and there are eroded features that are almost certainly older, larger impact craters, but really there are not very many craters considering Helene's location in the shooting gallery of the Saturn system, so whatever process makes these gullies has also very likely been active recently and has wiped away past smaller craters. This inference becomes even more interesting when you look at the opposite face of Helene, the one that faces out from Saturn, which is heavily cratered as you might expect. Ian Regan put together a really nice comparison of Cassini's various views of Helene's two faces:

Why are Helene's two sides so different? It's just one of many mysteries that Cassini's science team still has to solve.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth