Melissa Rice • Jun 15, 2011

The Spirit Rover, and Why Cuteness Matters

NASA made its final attempt to uplink a command to the Spirit rover on May 25. That afternoon, a group of us who work with the rovers at Cornell University gathered at a bar to mourn. We drank sangria outside, soaking up the solar energy that Spirit needed so desperately, and toasted the rover's seven years on Mars.

Although Spirit hadn't driven in over a year, and we all knew that this day would come someday, this official "last call" was hard news to receive. One former team member said that she broke down and cried as she read the email sent by project manager John Callas explaining to the team that this was the end for Spirit.

I had also held back tears when I read that email. I started wondering why we responded so emotionally -- why the official end of this rover could make grown scientists cry. Certainly part of it has to do with the community of the team. In planning meetings, the team tends to refer to the rovers as "we" as opposed to "she" or "it" -- "We'll do the Pancam imaging, then we'll drive west," for example -- and the end of a mission means the end of our shared experience.

But there's more to it than that, and there's more to it than the end of a compelling science campaign. And also -- for me -- more than knowing I'll never get more data for my thesis chapter on the Troy soil exposure.

No, there is something else about Spirit, something that separates this rover from every spacecraft that has come before, something that tugs at our hearts. I've had a hard time putting my finger on it, but I think I finally figured it out: it's cute.

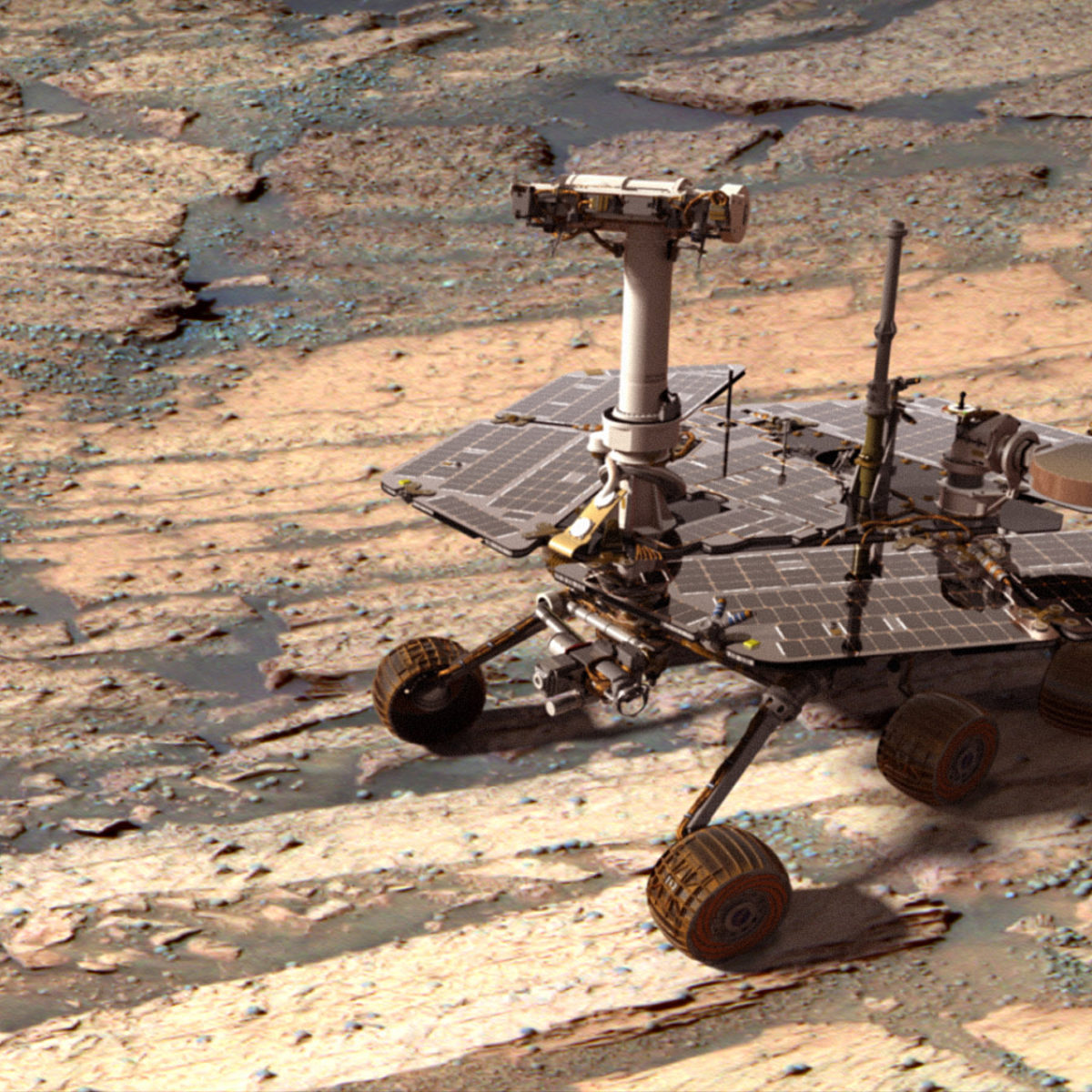

I'm serious. The Spirit and Opportunity rovers brought something brand new to space exploration: cuteness. The rovers' solar panels vaguely resemble wings, the camera masts look like long necks, and the Pancam instruments -- two on the top of each rover's mast -- seem to be the "eyes" of space-faring creatures. I'm certainly not the first to say this; in a press conference, Callas even called them "the cutest darn things out in the solar system."

Why is cuteness so important? Because humans tend to respond emotionally to cute things. We can't help it. It's hardwired into us, as it's related to our instincts to protect our young. OK, you say, but Spirit doesn't look at all like a human baby. To that I would reply: in ways that matter, it actually does.

It's not necessarily "human" characteristics that trigger this biological response in us; rather, it's the "juvenile" characteristics. Things that are cute tend to exhibit the characteristics that distinguish juvenile humans from adults, such as big eyes, flat faces, and large foreheads. These are the characteristics that make us go "awww" when we see puppies and that compel us to watch videos of kittens on YouTube.

These are the same characteristics that were exaggerated to make this xkcd cartoon about Spirit so heartbreakingly affective.

In a fascinating article (PDF) written for Natural History magazine, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote, "When we see a living creature with babyish features, we feel an automatic surge of disarming tenderness. The adaptive value of this response can scarcely be questioned, for we must nurture our babies." He argues that "abstract features of human childhood elicit powerful emotional responses in us, even when they occur in other animals," and provides this figure as an illustration:

Aren't the sketches on the left side cuter than those on the right? The same features that make the human baby cute are the ones that make the bunny, puppy, and chick look cute. The small eyes and long snouts of the full-grown animals on the right don't elicit the same emotional response. Gould said that we react to these features wherever we see them, even in drawings. And, I would add, even in robots.

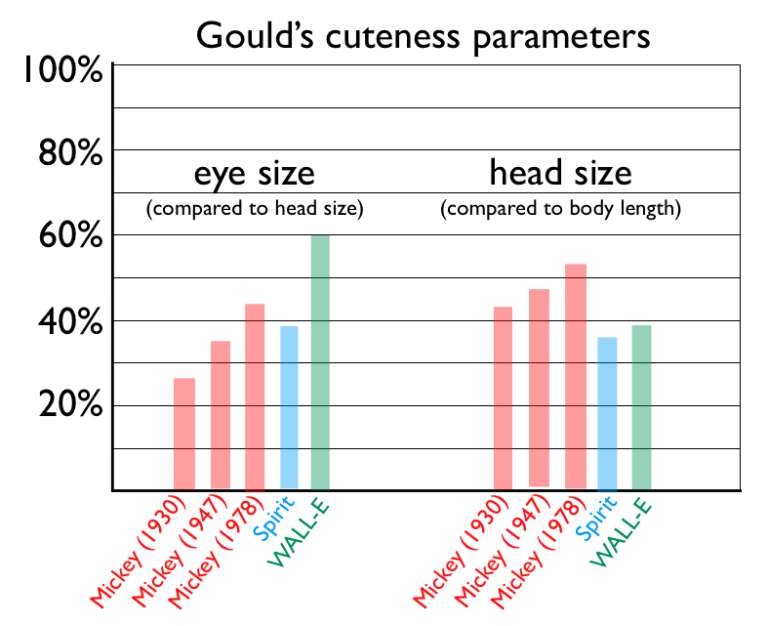

Gould also showed that we can quantify cuteness. In that same 1978 Natural History article, titled "A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse,"he measured three characteristics of Mickey's face to show that everyone's favorite mouse had grown cuter over 50 years: (1) eye size as a percentage of head length (base of the nose to the top of rear ear); (2) head length as a percentage of body length; and (3) cranial vault size measured by rearward displacement of the front ear (base of the nose to top of front ear as a percentage of base of the nose to top of rear ear). Looking at this series (which I won't post here out of respect for Disney's copyright, but you can see it if you download Gould's paper), it's easy to tell that Mickey is cuter now than he was in his Steamboat Willie days, and Gould says that's because his three parameters all increased.

I've taken a stab at measuring these same "cuteness parameters" for Spirit, to see how the rover compares to Mickey Mouse. I can approximate Gould's (1) and (2), using the size of the Pancams for "eye size," the height of the Camera Bar Drive plus the Pancams as "head length," and the distance between the bottom of the wheels and the base of the Pancam Mast Assembly as the "body length." (I can't really estimate Gould's (3) because Spirit has no cranial vault.) I've added Spirit's values to Gould's plot for Mickey:

So that settles it. Spirit is in the cuteness vicinity of Mickey Mouse. I've measured these parameters for WALL-E as well, which is really just a cuter version of Spirit.

I think this is why kids respond so strongly when I give presentations about the Mars Exploration Rover mission at schools and museums. No matter what age, they're always enthralled by the animation of the rovers, and they really seem to identify with these spacecraft. With kids under the age of 10 or so, I always get a question along the lines of, "do the rovers get lonely?" Once I even got, "do the rovers miss their mommies?"

And each time, while I explain to the children that the rovers are machines that have no real emotions, some deep part of me aches to travel to Mars and give lonely Spirit a hug.

Spirit's cuteness is, I believe, a big part of the public's response to the Mars Exploration Rover mission in general. It's why someone wrote LiveJournal entries for Spirit and Opportunity, giving them the personalities of vain teenage girls. (My favorite Spirit entry: "ARGH, can't i just explore mars in my own way? i don't need this constant ordering around! when do i get to make my own choices, anyway? it's my life, after all.")

It's why someone baked this cake for Spirit, with the rover anthropomorphized as a sexy young woman:

Spirit doesn't have to be a cute girl, however. MarsQuest Online uses a nerdy male anthropomorphism of the rover to help get kids interested in learning science (this guy reminds me of Mr. DNA from Jurassic Park):

I'm sure that Spirit and Opportunity were not engineered to be cute -- it was a bonus to their engineering design. But maybe it's something that should be kept in mind for future spacecraft. I'll be interested to see how the public response to Mars Science Laboratory (aka Curiosity), arriving at Mars next summer, compares to MER. It will be harder to anthropomorphize that beastly rover, with its off-center Cyclops eye (the ChemCam laser) and boxy frame. Even with its cutesy name, Curiosity isn't cute -- and it never gets the same "aww" response when I show pictures of it to kids.

Will the end of Curiosity's mission pull at our heartstrings the same way the end of Spirit's mission has? Hopefully we won't find out for many years. But for now: Goodbye, Spirit. We'll miss you, cutie.

Mars Exploration Rovers

The twin Mars Exploration Rovers (MER), Spirit and Opportunity, were robot field geologists. They confirmed liquid water once flowed across the Martian surface. Both long outlasted their planned 90-day lifetimes. Following their landings on 3 and 24 January 2004, Spirit drove 7.73 kilometers and worked for 2210 sols (Martian days), until 22 March 2010. Opportunity drove 45.16 kilometers and worked for at least 5111 sols; the rover stopped responding on 10 June 2018, and the mission was declared over on 13 February 2019.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth