Ted Stryk • Mar 17, 2011

LPSC 2011: Day 4: Ted Stryk on icy moons and The Moon

Here are Ted Stryk's notes from the sessions he attended in the afternoon of Thursday, March 10, at the 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Thanks Ted! --ESL

I spent the morning at the Lunar and Planetary library digging up some old Pioneer 10/11 and Venera materials for use in my own work. I arrived back at the conference center in the early afternoon. The first talk I attended was by Paul Schenk, who presented on the geology of Mimas. Mimas, due to its inactivity, provides a historical record of the Saturnian system that is useful for understanding other worlds such as Enceladus. A surprise is that the fractures on Mimas appear to predate Herschel, a crater which nearly shattered Mimas. However, given how well they align with Herschel, the coincidence required suggests that there may be an error in the relative dating. Schenk has found color variations across Mimas (its leading hemisphere appears relatively bright in the ultraviolet, its trailing hemisphere bright in the infrared). Most of this coloring is caused by exogenic (external) processes, such as the falling in of material swept up as Mimas orbits Saturn. No color differences are apparent in the floor of Herschel compared to the surrounding plains. To summarize the history of Mimas, soon after its formation, it had a global meltdown event that gave it its roughly spherical shape. It then underwent a period of global cooling which led to a global system of stress fractures. The Herschel impact had global geologic effects. Since then, Mimas has been steadily altered by ring particles and periodic impact cratering.

Mimas rotating The 140-km wide Herschel impact basin dominates Saturn's innermost regular icy satellite. The basin has a a deep bowl-shaped profile with a 5 kilometer high central peak complex. The floor is relatively free of craters and may have formed within the past 2 billion years. Video produced from Cassini imaging data by Paul Schenk, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston.Video: NASA / JPL-Caltech / SSI / Paul Schenk

Bonnie Buratti has been studying Mimas from Earth. It is clearly being coated by the E ring. The trailing side is brighter than the leading side, which is unique among the Saturnian moons.

Nico Schmedemann presented an attempt to narrow down surface ages on Mimas. He proposed that the old cratered plains are 4.35 billion years old, and Herschel 4.1 billion years old. His work was based on many assumptions, so the absolute ages are very approximate. A heavily eroded double impact basin that is nearly the size of Herschel is seen to the east of it, and is one of the older features on the cratered plains. Several people questioned the dating work, given that the plains are saturated. Crater saturation means that the entire surface is covered by craters, so every new crater destroys older ones. Thus, the crater count no longer increases with age.

Oliver White and Paul Schenk presented work using Cassini digital elevation models (DEMs) to measure the shapes of craters on the Saturnian satellites. Global maps for seven Saturnian moons are between .4 and 1 km/pixel, with high-resolution patches as good as 0.015 km/ pixel. These studies are useful in understanding the amount of relaxation of the crater topography, and thus the thermal history of these moons.

Francis Nimmo talked about limb profile studies of the icy Saturnian satellites and the "newly unfashionable" (his words) Europa. Some of the work studied surface roughness. The most interesting work dealt with using these profiles to infer global topography. He presented the Enceladus results, which had nice agreement with stereo-derived topography. Mixing the long wavelength limb measurement with high resolution low-frequency stereometric measurements should yield even better results.

I then migrated to the lunar session. Igor Miytofanov used the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) LEND neutron measurement to study the distribution of water on the Moon. The data indicates that the water in the polar cold traps may fall into three categories: primordial water from early cometary impacts; water that is trapped from passing comets; and water created from solar wind interaction with the surface, which is the most widely distributed and closest to the surface.

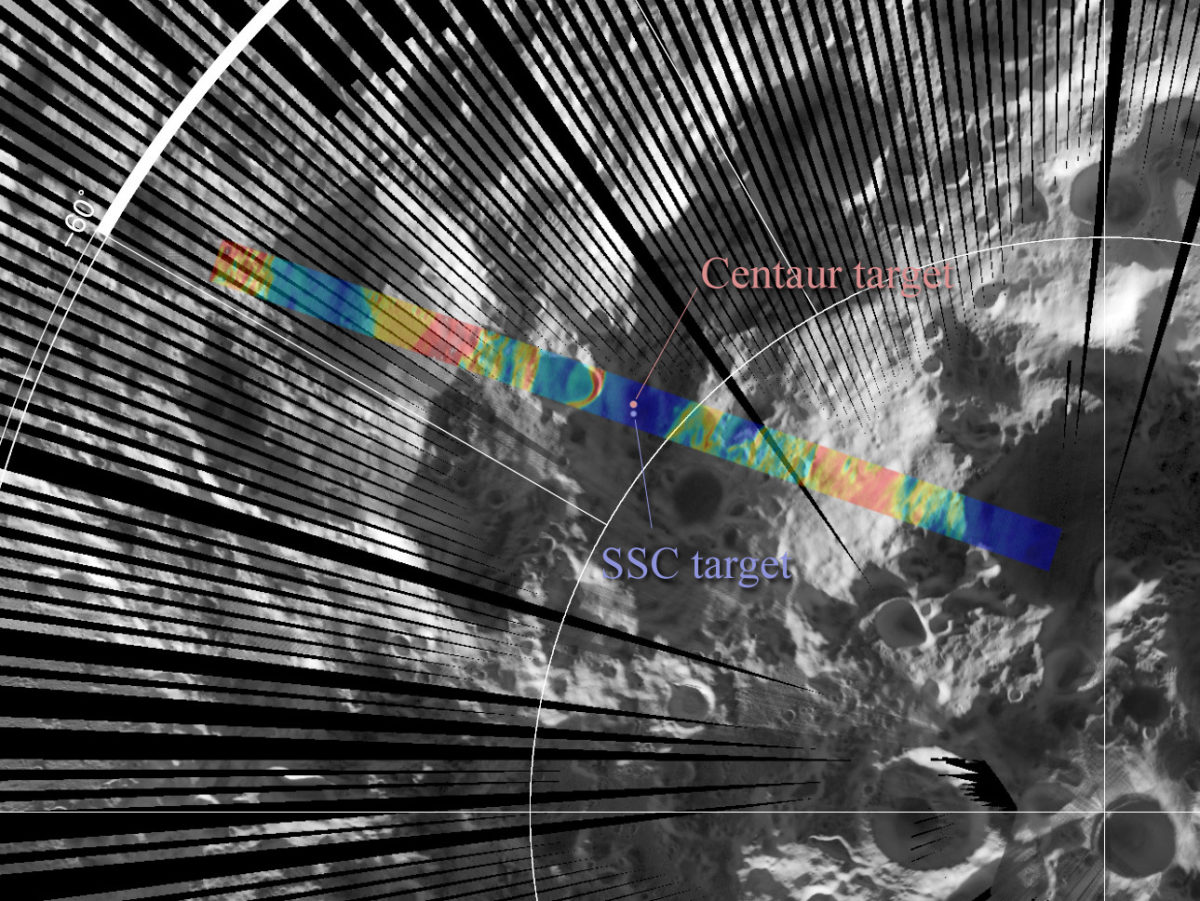

Bradley Thomson presented on LRO Mini-RF radar data on the floor of Shackleton, the crater which contains the lunar South Pole. These were merged with topographic measurements in order to better interpret the data and to see if evidence could be found to back the lone bistatic radar measurement from the 1994 Clementine mission that indicated an anomaly in reflectance due to ice on the crater floor. Reflection levels indicate that there is some water ice under the crater (in the form of a mix of 5% ice/95% rock, not in slab form), but its distribution is extremely patchy. In hearing this, I couldn't help but think that this will create headaches for anyone trying to design a lander to drill for the ice. Such a mission would have an extremely accurate landing system and/or be mobile.

The Lyman Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) instrument on LRO observed the LCROSS spacecraft's impact into the lunar South Polar region in 2009. Dana Hurley attempted to model the LCROSS impact plume, which largely consisted of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2). There was also a presence of mercury (Hg), magnesium (Mg), and Calcium (Ca). The temperature probably did not exceed 1000 Kelvin during the impact.

Richard Elphic used the LRO DIVINER instrument to study the amount of water in the lunar crater Cabeus, which contains the LCROSS impact site. Parts of the floor of Cabeus are cold enough to contain stable ice at a depth of only a few centimeters. This work seems to resolve the conflict between LCROSS and some orbital measurements which showed far less water than was seen in the LCROSS plumes. In addition to the amounts of water being spotty, its depth is also highly variable. Instruments on missions such as Lunar Prospector, which had very low spatial resolution, averaged across high and low concentration areas and couldn't compensate for different depths, which led to scientists underestimating how much water might be present in a given amount of soil. Attempts are now being made to model exactly what the distribution of underground ice might be.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth