Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 01, 2010

Door 1 in the Planetary Society Blog 2010 advent calendar

December really has arrived, and that means that the year is racing to a close. Last year, I counted the days to the New Year with an advent calendar, where each "door" opened onto a global image of a different world in the solar system, all processed by amateurs. As I explained last year, I do realize that the "advent" part of this calendar refers to Christmas, but I'm doing this my own non-denominational way by counting to the New Year instead, which has the added benefit of permitting me to include more places in the solar system. Also, I'll be the last one standing after the Boston Globe Big Picture Hubble and Zooniverse advent calendars run out!

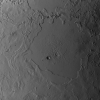

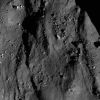

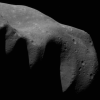

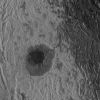

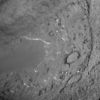

Last year, the theme was global views. This year, the theme will be the solar system's often strange landscapes. Here's the first. Can you figure out what solar system body you're looking at? Make a guess before you scroll down.

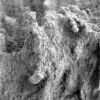

We're looking at Saturn's moon Hyperion, in a closeup taken during Cassini's one and only targeted flyby of Saturn's spongy moon, on September 26, 2005. (Here's a page on the flyby images that I put together back then, so you can see all the weird views of the moon.) Hyperion's surface texture is bizarre; what you or I would describe as "spongy" is described by scientists as "a high surface density of relatively well-preserved craters two to ten kilometres across." If you look closely at the photo, you'll see that some craters are preserved better than others; some have evident scarps, while others are smoother. Several have deposits of very dark material inside.

The Cassini scientists hypothesize that Hyperion preserves these craters better than other smaller Saturn moons because Hyperion is so porous; Hyperion's density is only half that of pure water ice, so the moon has to have more than 40% open pore space in its interior. When smaller bits of rock and ice strike such a porous surface, they make craters but don't fling up very much ejecta, so there isn't a big supply of dust and pebbles around to smooth out Hyperion's craters. Which seems like a reasonable explanation to me; but now I wonder why Hyperion is so incredibly porous!

As for the dark floors, they may be sites of runaway thermal segregation, where a tiny bit of dark material in the floor causes the floor of the crater to warm up, which encourages the ice below it to transpire into vapor and float away and freeze back to the surface in some colder location (or escape Hyperion entirely), concentrating the dust in the floor, causing it to get darker, which makes it warmer, and so on. It's the same process that's thought to operate on Iapetus, making its leading side dark and its trailing side bright.

Four images were taken through clear, infrared, green, and ultraviolet filters; the color-filter images were at half the resolution of the clear-filter image. To make this composite, I enlarged the three color-filter images and aligned them to the clear-filter image. I composed the color frames into an RGB image, converted it to Lab color, and then swapped a sharpened version of the clear-filter image in to the Lightness channel.

So, I hope you enjoy this and the following 31 doors in the Planetary Society Blog 2010 advent calendar. Each image will be square and will fill the frame from edge to edge. With these kinds of images it's impossible to know what the scale is unless you are told (or unless you recognize features, of course), and it can sometimes be a challenge to figure out exactly what world you're looking at. I won't limit myself to amateur-processed views this year. Got ideas for something that should be included? I encourage anyone who's reading this to nominate images by sending me an email.

The Planetary Society Blog 2010 Advent Calendar

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth