Emily Lakdawalla • Nov 04, 2010

Five close-approach images of Hartley 2 by Deep Impact, with commentary

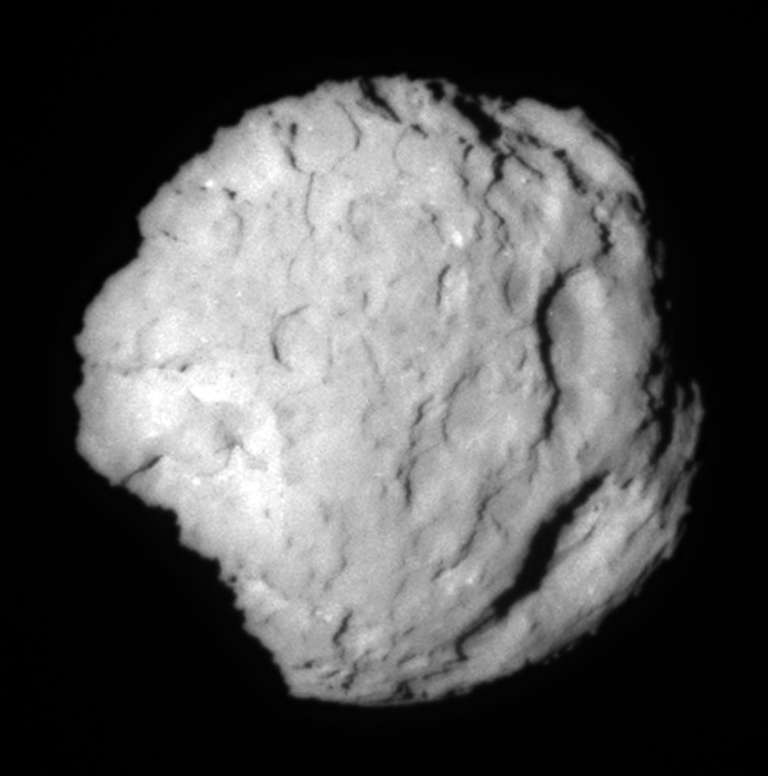

Here's the five close-approach images of Hartley 2 captured today, November 4, 2010, by the Deep Impact spacecraft, collected into one file. Boy, do these images reward close examination! Check them out (and also see my animation of them):

I suggest you click to enlarge and investigate them for yourself before you read my description. Put on your scientist hat. What do you notice? What strikes you as being surprising or strange?

Here are the things that I notice when I look at them.

The comet nucleus has two lobes. This much we knew already from the radar images. But there is a surprising (to me) narrow and concave neck connecting the two. Furthermore, that neck is very, very smooth. What I think we are seeing here is a contact binary, two main bodies that orbit each other so closely that they are touching. Gravel and dust has flowed into the weird gravitational region between the two lobes, filling it almost as though it were a liquid. I'll bet that smooth neck traces out an equipotential surface. In shape, this comet looks very similar to Borrelly:

Hartley 2 has lots and lots of jets. It would be a fun activity to use the five images to triangulate and trace the jets back to their sources. I think that work will get easier with more images; I think there are more images in between these, yet to be downlinked.

There are some huge boulders on those lobe ends. That's much like Itokawa, another very small body that's been visited by a spacecraft. Hartley 2 is maybe 4 or 5 times larger (in diameter) than Itokawa, but is still the smallest comet yet visited by a spacecraft.

There are some very interesting looking valleys and dents in the comet. One on the larger lobe end reminds me of the "footprints" in Wild 2, the comet that Stardust first visited.

There are several noticeable ridges on Hartley 2, ridges that seem to be circumferential to the long axis of the comet. That's interesting; I don't know what geophysics could cause that. Ridges usually arise from compression (squeeze things together and stuff pops up in between, with the ridge perpendicular to the direction of the squeeze) but they can arise from extension (pull things apart and you open up cracks; the edges of those cracks make cliffs).

That's what I see. What do you see?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth