Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 26, 2010

A couple of tidbits from today's Deep Impact preview briefing

Today was the press briefing that previewed the upcoming Deep Impact flyby of Hartley 2. This briefing wasn't particularly well attended by press, because it's the sort of briefing where almost all of the information they would be relaying was already released -- these preview briefings are mostly for press who haven't been paying much attention. So there weren't any real surprises, as expected; most of what was said has already been mentioned in such places as the Deep Impact Hartley 2 flyby timeline I posted last week. (I should mention that I have recently corrected some errors in the timeline, most importantly my incorrect time conversions to UTC; I hadn't realized that Daylight Saving Time was still in effect here in California through November 7. To make things more confusing, this flyby is happening during the week when Europe will have shifted back from Summer Time, but the USA is still under Daylight Saving Time. Everything in my timeline should be fixed now.)

Still, there were a few interesting tidbits worth reporting. Tim Larson, EPOXI mission project manager, said that the 700-kilometer flyby distance was chosen both for spacecraft safety (to keep the spacecraft far enough away from the coma and its dust) and to allow it to track the comet nucleus comfortably within the spacecraft's maximum turn rate. For comparison, Deep Impact flew within 500 kilometers of Tempel 1.

Amy Walsh, EPOXI systems engineering lead at Ball Aerospace, said that the spacecraft launched with 85 kilograms of hydrazine maneuvering fuel. Five kilograms remain. One kilogram will be consumed between now and the end of this flyby. She pointed out the positions of the low-gain antennas on the spacecraft -- there are two, one on the side with the instruments and one on the side with the solar panel -- and she said Deep Impact should be sending telemetry through these antennas to Earth throughout the flyby, while the high-gain antenna will be pointed away from Earth.

Mike A'Hearn, principal investigator, said that Hartley 2 was chosen because it was small; they wanted to see something smaller than had been visited before. (Hartley 2 is thought to be 1.2 kilometers across, while the mid-sized comets we've visited before are 4-8 kilometers across.) He said that Hartley 2 was identified as a possible target as early as the time of the Tempel 1 encounter, but a different comet (Boethin) was selected first because the mission to it would be shorter. But Boethin completely vanished, which he said was likely due to its utter breakup. Boethin's disintegration was not witnessed but he showed an image from Hubble of another comet, LINEAR, breaking up. A'Hearn said that comet breakups are thus rare but not unprecedented.

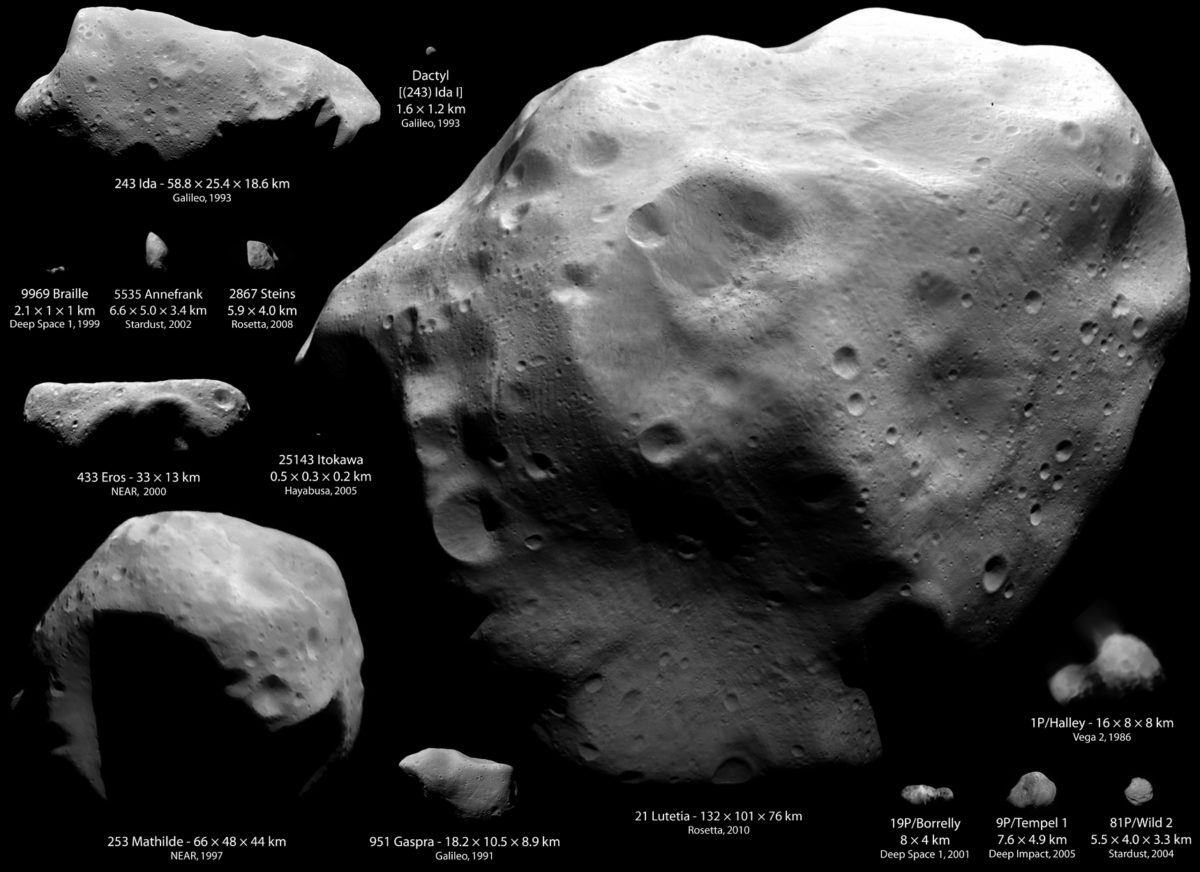

The total of four comets and nine asteroid systems (including ten separate bodies) that have been examined up close by spacecraft are shown here to scale with each other (100 meters per pixel, in the fully enlarged version). Most of these were visited only briefly, in flyby missions, so we have only one point of view on each; only Eros and Itokawa were orbited and mapped completely. When Hartley 2 is added to this montage, it will appear approximately the same size as Dactyl or Braille -- much smaller than the other four comets that have been visited to date (which are grouped in the lower right corner).

This image is also available without text, and as a larger version at 20 meters per pixel (8600x6250 pixels, 9.4 MB).

Image: Montage by Emily Lakdawalla. Ida, Dactyl, Braille, Annefrank, Gaspra, Borrelly: NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk. Steins: ESA / OSIRIS team. Eros: NASA / JHUAPL. Itokawa: ISAS / JAXA / Emily Lakdawalla. Mathilde: NASA / JHUAPL / Ted Stryk. Lutetia: ESA / OSIRIS team / Emily Lakdawalla. Halley: Russian Academy of Sciences / Ted Stryk. Tempel 1: NASA / JPL / UMD. Wild 2: NASA / JPL.A'Hearn said that despite Hartley 2's small size, it puts out more gas every minute than Tempel 1.

He showed a video of ten days' worth of Deep Impact's observations of Hartley 2, which is very cool and worth watching several times. It jumps a bit because Deep Impact watches the comet for about 16 hours then turns to communicate with Earth for 8 hours. As the video goes on, you can see the comet brighten, which results from two things: the decreasing range from the spacecraft to the comet, and also the comet's increasing activity as it approaches perihelion (it passes perihelion on Thursday). You can also see that its activity is variable; you can even see jets of material coming out, at least I think I can see that. I asked A'Hearn if they could identify the comet's rotation pole yet and he said that ground-based telescopes still provide better data for that than the spacecraft does; but that rotation poles measured by astronomers using different ground-based telescopes are inconsistent.

One of the press asked a question about the layering on comet Tempel 1, and A'Hearn told a really interesting story about that. He said Tempel 1 has many layers ranging in thickness from 10 or 20 meters to half a kilometer. The solar system started forming with tiny dust grains accreting into bigger and bigger things. It started just with solids -- ice and silicates. Eventually you get a discrete body. Theories have predicted that once they grow as large as something like 50 or 100 meters, then they start to run into each other. It looks like layering on Tempel 1 was produced by multiple cometesimals coming together; the smaller one sticks to the nucleus by flattening out. It doesn't interpenetrate with the larger comet's substance. It doesn't compress a lot, we know, because comets' bulk density is low, they're highly porous. So we think this tells us how accretion at 50-100 meter size works. We don't have a numerical model of this though. It's a challenging thing to model.

The physics hasn't been worked out yet though, so it's kind of just a fairy tale story of unknown degree of possible-ness -- but it's one that I hadn't heard before, and fascinating to contemplate.

I asked also about the HRI images and how their processing was going to work. Deep Impact's highest-resolution camera has an intrinsic blur. A'Hearn said that the processing of those images will be done using methods established during the Tempel 1 encounter, but that the processing has to be numerically tuned in order to avoid "ringing" artifacts in the images. He said that the person who handled this for the Tempel 1 flyby will be at JPL to handle the processing for the Hartley 2 flyby.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth