Emily Lakdawalla • Oct 06, 2010

DPS 2010: Making Saturn's rings and moons all at once

It's already Wednesday and I've written up nothing from this week's Division of Planetary Sciences meeting yet -- time to get cracking! I'm going to take a stab at doing some shorter posts kept to single topics...

One of the most interesting talks I saw on Monday was Robin Canup's, "Origin Of Saturn's Rings Via Tidal Stripping From A Primordial Massive Companion To Titan." Canup is well known for her work creating computer models of the formation of the solar system and of the mini-solar systems, the giant planets and their moons and rings. About a year ago, she published some work in which she showed that when Jupiter and its moons formed, a great many more moons initially nucleated, as many as 20 of them the size of the Galileans, but as they interacted with the gas and dust swirling around Jupiter their orbits decayed until they crashed into the planet. The four big moons we see there now are just the last four that formed. Jason Perry has a great writeup of this work on his blog.

Well, Canup has now turned her attention to Saturn, and holy cow, not only can her models produce the one big and several small moons we see there today, but she can make the rings too, and even explain why they are so rich in ice, plus she can explain why the innermost moons are also nearly pure ice. In short, these rings...

NASA / JPL / SSI

Saturn's complete ring system from the north

Cassini captured the images composing this view of Saturn's entire main ring system on January 21, 2007 while on an orbit that took it 60 degrees above the plane of the rings. Cassini looks upon Saturn from its winter-shadowed north pole. In order to reveal subtle details on the shadowed side of the rings, the camera's view of the planet itself was overexposed, so the planet has been removed from this view. Moons visible in this image are Epimetheus at the 1 o'clock position, Pandora at the 5 o'clock position, and Janus at the 10 o'clock position.

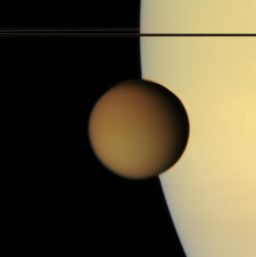

NASA / JPL / SSI

Titan and Saturn

This view of smoggy Titan against the limb of Saturn is composed of photos taken by Cassini on August 1, 2007 through red, green, and blue filters, so it shows the moon and planet approximately as they would appear to the human eye. Titan's absorbing atmosphere is much darker than Saturn, whose light shines through Titan's upper haze layers, particularly the north polar hood.![Titan's internal structure [DEPRECATED]](http://planetary.s3.amazonaws.com/image/titan_old_med.jpg)

Doug Ellison

Titan's internal structure [DEPRECATED]

The next-to-last large moon to form in the Saturn system would have differentiated into an ice-rich mantle, probably with an ocean, and a rocky core, possibly even with a metal inner core. Canup's story is that the ice part got stripped off to make the rings, while the rocky-iron part collided with Saturn.But at this time, early in Saturn's history, when it was still accreting and still hot, its was bigger, more bloated than it is now (its mass was basically the same, but its width was larger). From the birth of the solar system to about five million years of age, Saturn's radius was about 1.7 to 1.4 times its current size. Our penultimate-Titan's orbit keeps decaying, and its icy mantle keeps getting stripped off, but because Saturn is bigger, our moon's core with all its rock runs in to Saturn's atmosphere, colliding and getting eaten, before it ever gets to the Roche limit for rock. What you end up with is a really, really massive ring system made of nearly pure ice.

This incredibly massive ring "does what rings do," Canup said -- it spreads. Some material spreads inward and so is eaten by Saturn. But, in conservation of angular momentum, some spreads outward. Ring material that spreads outward beyond the Roche limit for ice can re-accrete. Canup's model creates not only ice-rich rings but several mid-sized moons that are almost 100% ice, everything out to Tethys. (Dione, Rhea, Titan, and everything beyond would have formed by condensing from the original nebula, not by re-accreting from this primordial ring.)

Canup said that the biggest difference between this model and previous ones of Saturn's rings is that her model produces a much, much more massive initial ring. It explains the ice-rich moons, and the more massive ring is "less vulnerable to pollution by rocky material," explaining their present, bright, youthful, ice-rich appearance.

It's a model, not a proof, but nearly every scientist I chatted with about this paper really liked it, and said it was one of the more important ones presented on Monday.

As a postscript, I'll mention that I ran in to Larry Esposito, who is a senior rings scientist (he discovered Saturn's F ring while working on Pioneer), and by the way was Canup's grad student advisor back in the early '90s. Every time I run in to Larry I like to ask him whether Saturn's rings are old or young (which is shorthand for: did they form initially, when Saturn formed, or do they result from the recent disruption of a moon?) It's a debate that's been going on in the rings community forever. Today Larry's answer was "yes." And he told me this cute simile: Saturn's rings are like the cats in the Roman forum. They're recent and continuously changing things residing among the most ancient of constructs. By this he means that the rings are ancient, but their appearance is continuously being refreshed by their dynamics.

(So much for writing a short post.)

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth