Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 16, 2010

A bull's eye on the Moon

Orientale is the youngest large impact basin on the Moon, which means that very little of it has been obliterated by later impacts. Its three or four (or maybe even more) concentric rings are beautifully preserved, frozen ripples in the lunar crust left behind when a pretty enormous "pebble" splashed into it around three and a half billion years ago. By studying Orientale, planetary geologists have learned a lot about exactly what happens to a planet when a big thing crashes into it, an event that happened to all the planets and moons many times over their long lives.

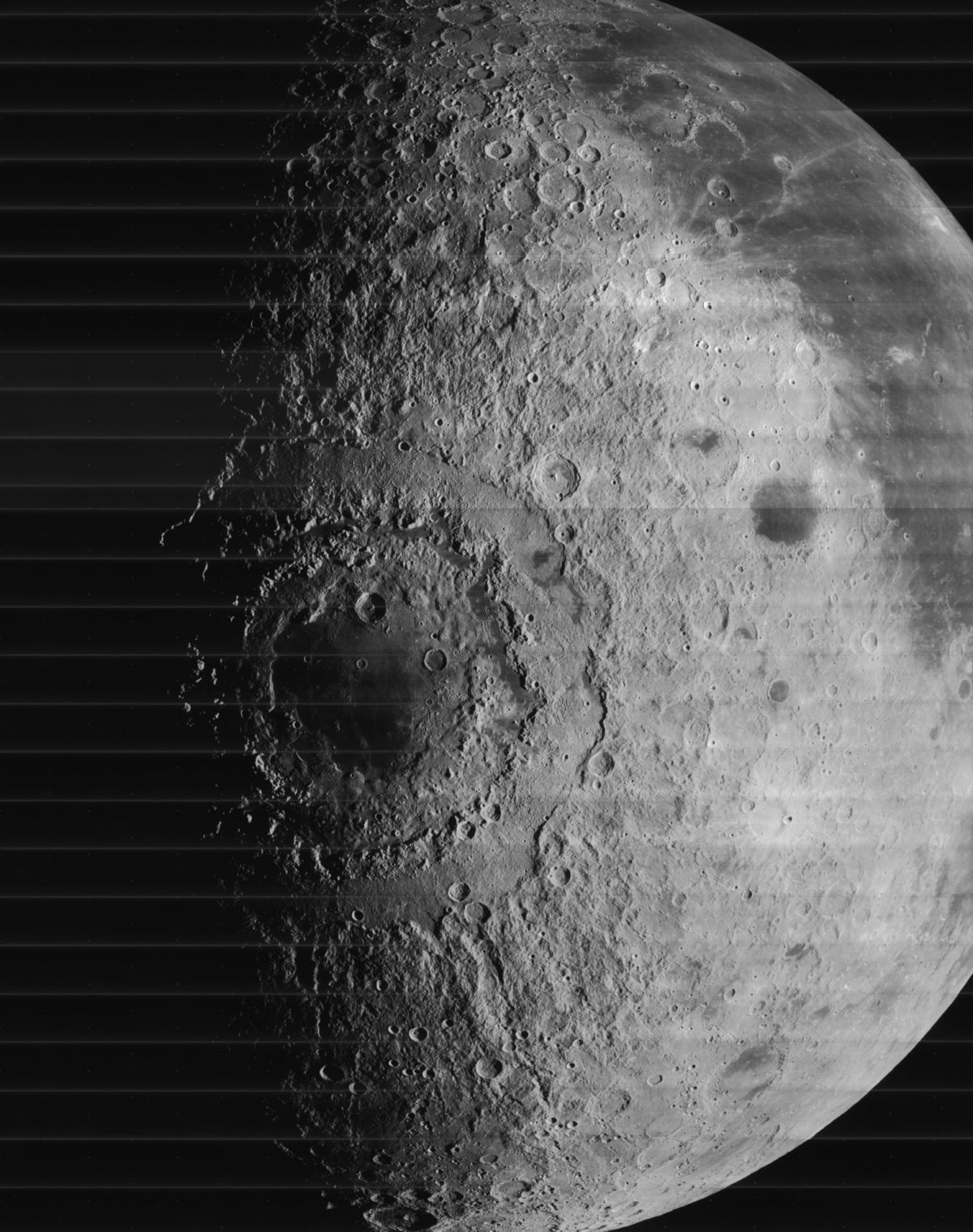

It's hard to study Orientale with Earth-based telescopes, because it's centered just off the lunar nearside; we can only see its eastern rings. But the Lunar Orbiters took great photos of it. Here's the classic view, from Lunar Orbiter IV.

This image seems to be one of the favorites from the Lunar Orbiter missions. I think that's because it can be used either to illustrate the new discoveries revealed through our first systematic mapping missions, or to emphasize what we had yet to learn. The view looks down on Orientale, revealing its many concentric rings through dramatic dawn lighting, in a view impossible from Earth. To the right, the near side of the Moon with its familiar, huge Oceanus Procellarum is well-lit by the Sun; to the left, the far side of the Moon, totally unknown to humans before the Space Age, is hidden in darkness.

This image helped us learn a lot about Orientale, but it has its problems. The basin is so large, stretching across so much of the Moon, that parts of it are well-lit, while parts of it are lost in the predawn darkness; it's something like 8:00 a.m. local solar time in its easternmost parts, while it's more like 4:00 a.m. in its westernmost parts. That change in local time and corresponding change in solar illumination angle across its expanse makes it difficult to do systematic mapping. In the better-lit areas, we can see albedo differences, places where the surface is made of more or less reflective material, but it's harder to see the wrinkly texture of the basin ejecta; in the more dramatically lit areas, the reverse is true.

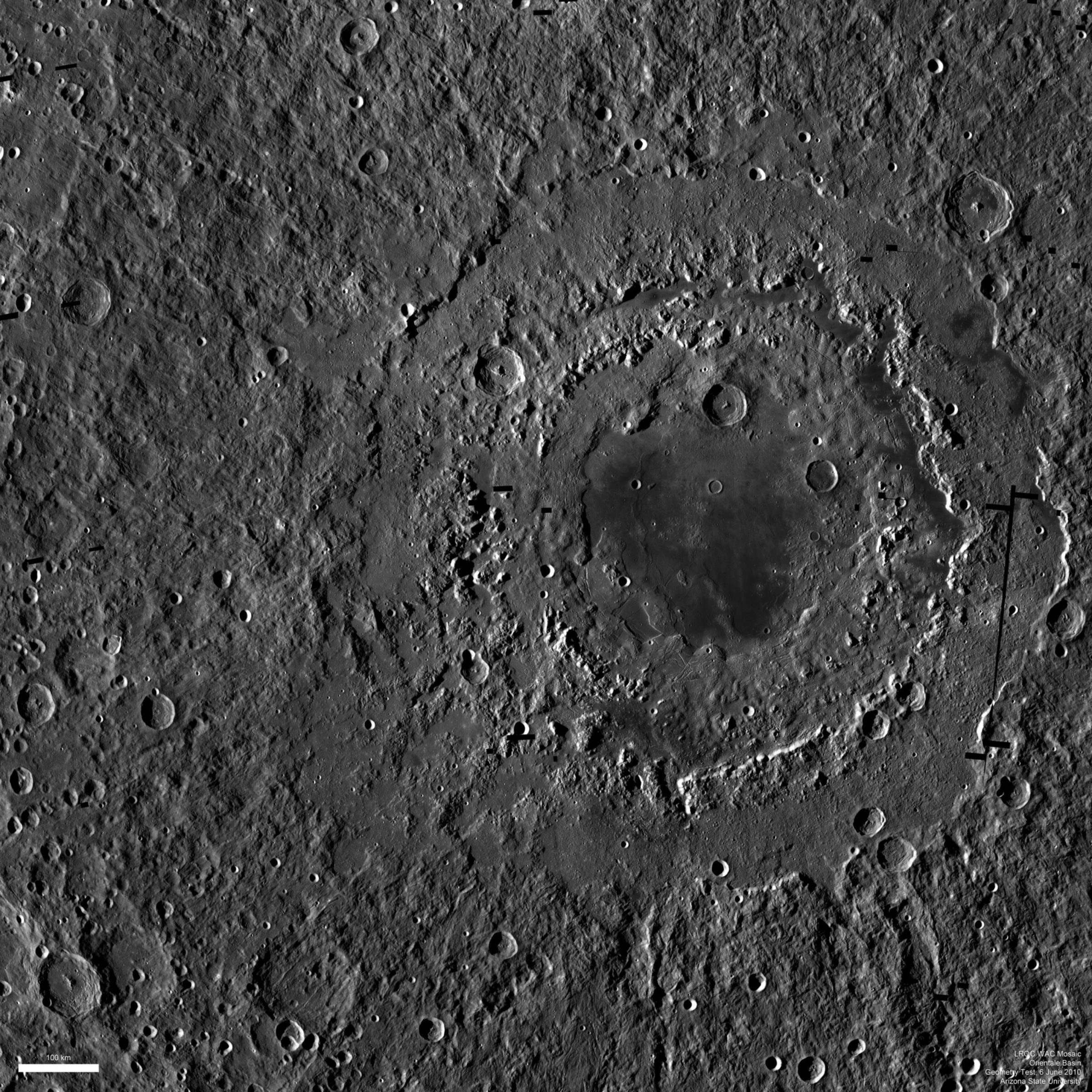

To see Orientale under more consistent lighting, it won't do to take just a single snapshot. We have to take photos of each part of it at the same local time of day, longitudinal strips across it with consistent solar illumination. Then we need to assemble those strips into a seamless global mosaic. That's the goal of Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera's wide-angle camera instrument, and some recent image releases from that science team show that they are making great strides on that project. This mosaic covers almost all of Orientale, with only a few small gaps in the data here and there.

A few things jump out at me when I look at this mosaic, which I didn't notice when I looked at the Lunar Orbiter view. First, you can tell from how bright the cliffs are that the inner two rings of mountains are much steeper than the outer ring. Second, while I had noticed the mare basalt (dark, flat lava plains) filling the very center of the basin in the Lunar Orbiter view, I had not noticed the fact that there seem to be some dark basalt flows pooled just interior to the second ring, and even a tiny bit of it pooled interior to the outermost ring, but only on the lunar nearside (the right side of the image). Take a tour around the photo for yourself, and see what you find! The "click to enlarge" version on this page only takes you to a fifth of its full resolution. Here's a small area of the picture shown at full resolution, 100 meters per pixel.

I love the mix of tectonic and volcanic features in this region. Tectonics refers to the cracking, folding, and bending of the crust, the building of the mountains and the cracking apart of the volcanic plains. But some of those tectonic cracks have been widened through volcanic activity, and they terminate in little squiggly lava channels. Really neat stuff, and a complicated geologic story to tease apart. I think planetary geologists ought to cut their teeth trying to explain lunar geologic features before they go on to trying to explain geologic features on even more complex places like Mars or Europa.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth