Emily Lakdawalla • Jul 07, 2010

Three days to Lutetia for Rosetta!

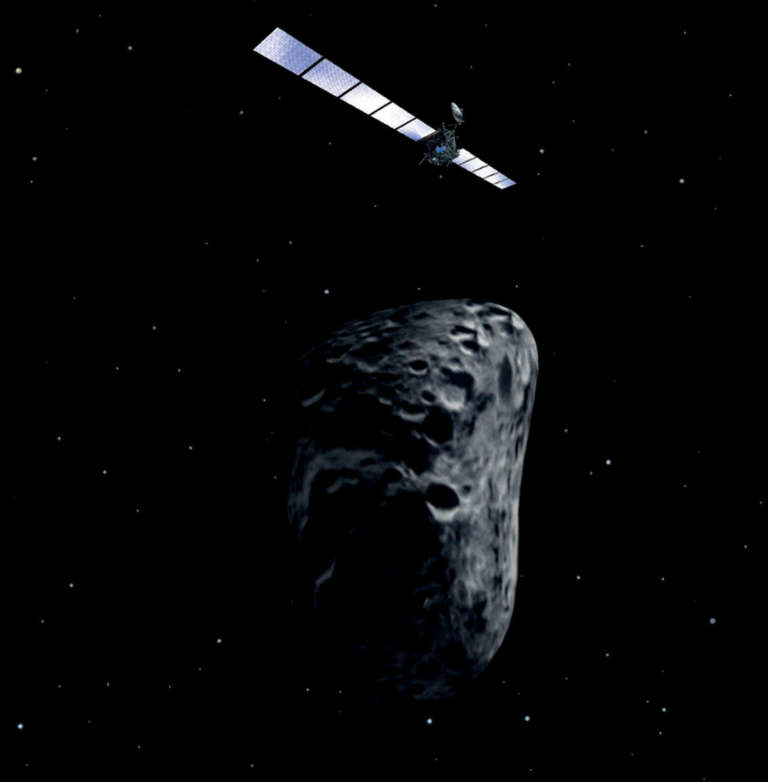

On July 10, 2010, at 15:44:56 UTC, the Rosetta spacecraft will fly within 3,162 kilometers of the largest asteroid yet visited by a spacecraft. Named (21) Lutetia, the 132-by-101-by-76-kilometer-diameter body is a puzzle to astronomers, who have been unable to determine its composition. Both the Rosetta orbiter and its still-attached Philae lander have a full slate of science observations planned for the encounter, which will serve both as a test of its instruments and procedures to prepare for its eventual cometary mission and as an opportunity to observe a unique solar system body.

The asteroid is slowly growing in Rosetta's forward view. Here's the latest photo, published to the Rosetta blog just now:

Unfortunately, I won't be able to watch the whole event live, but, fortunately, you will. That's because ESA is doing a live stream webcast to help people around the world follow one of the biggest space events of 2010. You can watch ESA's streams here, here, or here; I also plan to embed the live stream into a blog entry here on Friday night my time. I'll also provide links to anybody I know of who plans to be live-Tweeting the encounter and who might be a reasonably knowledgeable commentator. I am hoping that Andy Rivkin will be one such commentweeter; his thesis was actually observational work on Lutetia! If live streams are not your style or if you'll be enjoying your Saturday outdoors or at a World Cup party, you can keep up with events via ESA's terrific Rosetta blog. I'll be tuned in to the beginning of the events but will be on a plane when the first images are expected to be released.

To review, since its February 2004 launch, Rosetta has wended its way around the solar system on its long, long, long journey to comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko; it arrives there in May 2014. The Lutetia phase of the mission began after the successful gravity-assist flyby of Earth in November 2009. The first, necessary activity was to test the spacecraft's capability to perform autonomously a critical and difficult maneuver, a quick spin needed to protect Philae from too much sun exposure while at the same time permitting the cameras to remain locked on the approaching asteroid. The test, conducted on March 15, was successful.

Following checkouts of all its instruments, Rosetta began optical navigation of Lutetia on May 31. At that time, Lutetia was the tiniest speck among background stars. Although Lutetia is a large asteroid and therefore not as challenging to track from Earth as its smaller neighbors, optical navigation by the spacecraft is still critical to ensuring that Rosetta passes by Lutetia at the right distance and with the right position with respect to the Sun. Too far, and Rosetta will fail to achieve the best possible science at the asteroid; too close, and the asteroid will more than fill the view of the spacecraft's cameras, with parts of it cut off at the edges of images. In addition, scientists want the spacecraft to pass precisely between Lutetia and the Sun, permitting the cameras to see Lutetia's surface at "zero phase" -- that is, fully illuminated by the Sun -- a geometry that will aid scientists in understanding the nature of Lutetia's surface.

The optical navigation campaign continues through July 9. Through June, Rosetta captured images about twice a week; for the final two weeks of the approach, from June 28, Rosetta was commanded to image Lutetia daily. Engineers on the ground will use these images to determine whether the spacecraft needs to perform trajectory correction maneuvers (TCMs) to aim it more precisely at the asteroid. There are four opportunities for TCMs before the flyby: seven days, three days, 40 hours, and 12 hours before closest approach.

The encounter will happen fast, at a relative speed of 15 kilometers per second, so Rosetta's cameras will only resolve Lutetia as more than a speck of light for a few hours around closest approach. Four hours before closest approach, Rosetta will perform its flip while keeping the asteroid in its field of view. The flip will take 40 minutes to complete. At about 12:45 UT, the spacecraft will begin autonomous tracking of the asteroid, examining its own navigational images to ensure that the asteroid remains within its science instruments' field of view.

Five minutes before closest approach, at about 15:40 UT, as Rosetta continues tracking the asteroid, its high-gain antenna will rotate off of Earth line. As the spacecraft is too distant from Earth (more than 3 astronomical units) for the signal from its low-gain antenna to be detectable, this means that communications will cease until after the encounter has ended and Rosetta has turned toward Earth again. It takes 25 minutes for its signals to reach us, so the loss of signal is expected to begin at about 16:05 on Earth. It should last for about 40 minutes, until 16:45 UT. On-time reacquisition of the signal will be ESA's first indication of a successful flyby.

The media has been invited to the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany, to witness these exciting events. But once the signal has been reacquired, there will be a couple of evening hours to wait for more news to report on, as the spacecraft will still be recording data and will not yet be ready to downlink it. ESA plans to entertain the media during this waiting period with a garden barbeque and TV broadcast of the World Cup third place game, in which either Spain or Germany will be playing Uruguay. Should be a lively party!

Following the flyby, the first data to be downlinked, beginning at 18:05 UT on Earth, will be that from the main science cameras, OSIRIS. It will take many hours for all the science data to be transmitted. Mindful of media interest in the encounter -- but also of the World Cup schedule -- ESA plans to have the first black-and-white images prepared for public release around 21:05 or possibly later if the Third Place match runs into overtime. (If this frustrates you, it shouldn't. Why try to make a media fuss out of something when pretty much all of Europe's attention is going to be elsewhere?) The schedule assumes, of course, that everything has worked perfectly from acquisition of the data through onboard storage, transmission, and reception on Earth. The first color images may possibly be available as early as midday Sunday, but it might take more time for the OSIRIS team to process them to their satisfaction.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth