Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 25, 2010

In which I dip my toes into an ocean of Hubble data

I am just drowning in data right now, and I couldn't be happier. Yesterday, while I was in the middle of an occasionally frustrating session of trying to figure out how to locate interesting stuff within the unbelievably massive Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera data set, I received an email from the Space Telescope Science Institute: "The fourth major data release (DR4) for the Hubble Legacy Archive (HLA) is now available at http://hla.stsci.edu. DR4 provides new kinds of data, substantial improvements in several classes of existing data, and enhancements in the user interface."

Now, I can't remember signing up for this mailing list, or ever having seen the Hubble Legacy Archive data browser before. I went to check it out, and, whoa. Holy cow. It provides unbelievably easy access to Hubble's public data, more than 16 years' worth. The most recent data available on a planetary target was taken only last month, on February 12, some views of Kuiper belt objects 2000WK182, 2000YB2, 2000YH2, and 2003UZ117 using the newly installed Wide Field Camera 3, with Mike Brown as the principal investigator. (You'd better analyze that data fast, Mike!)

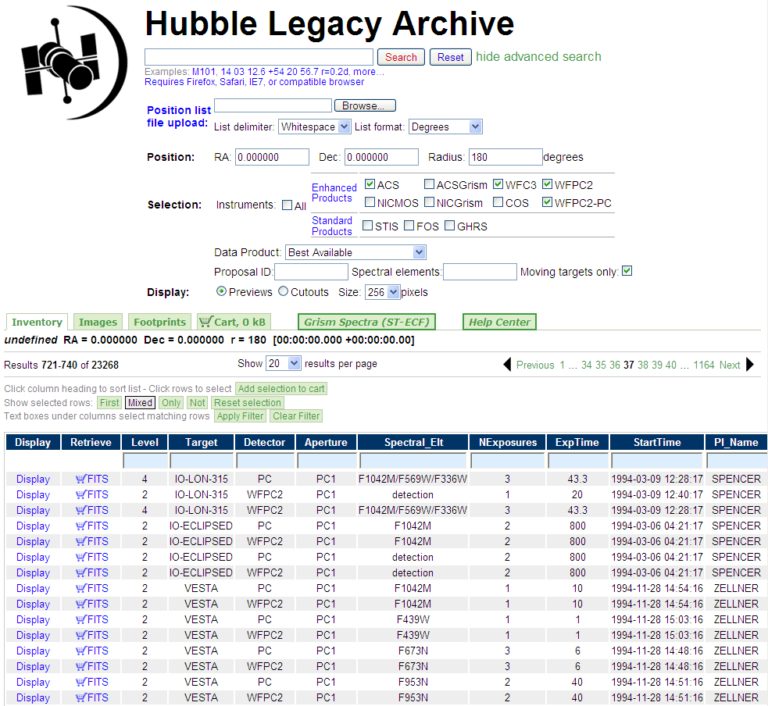

There are some tricks required to locate data. Fortunately, there was a five-minute video tutorial on using the data browser, which is necessary to watch if you want to have any idea what you are doing with the data browser. And make sure you watch it through to the end, because it's in the last seconds of the video where it shows you how to search for moving targets -- that is, planets, asteroids, comets, and the other stuff that I'm interested in.

So I followed the video directions and searched the database for all moving targets as seen by Hubble's main camera instruments: ACS, WFPC2, the WFPC2 PC, and WFC3. (I didn't include NICMOS because if I dive into Hubble data I am really most interested in high-res images taken in visible wavelengths.) After chugging for some time, the browser returned nearly 24,000 unique observations.

That's a bit much to browse, but fortunately the browser makes it super duper easy to filter your results. Want to see Hubble's images of Vesta? Just place your cursor into the little text box at the top of the "Target" column and type in "*vesta*" (you need the asterisk wildcards so you can make sure to get observations labeled as "4-VESTA" or other things that aren't just "VESTA.") There are 319 entries in the database with that filter applied.

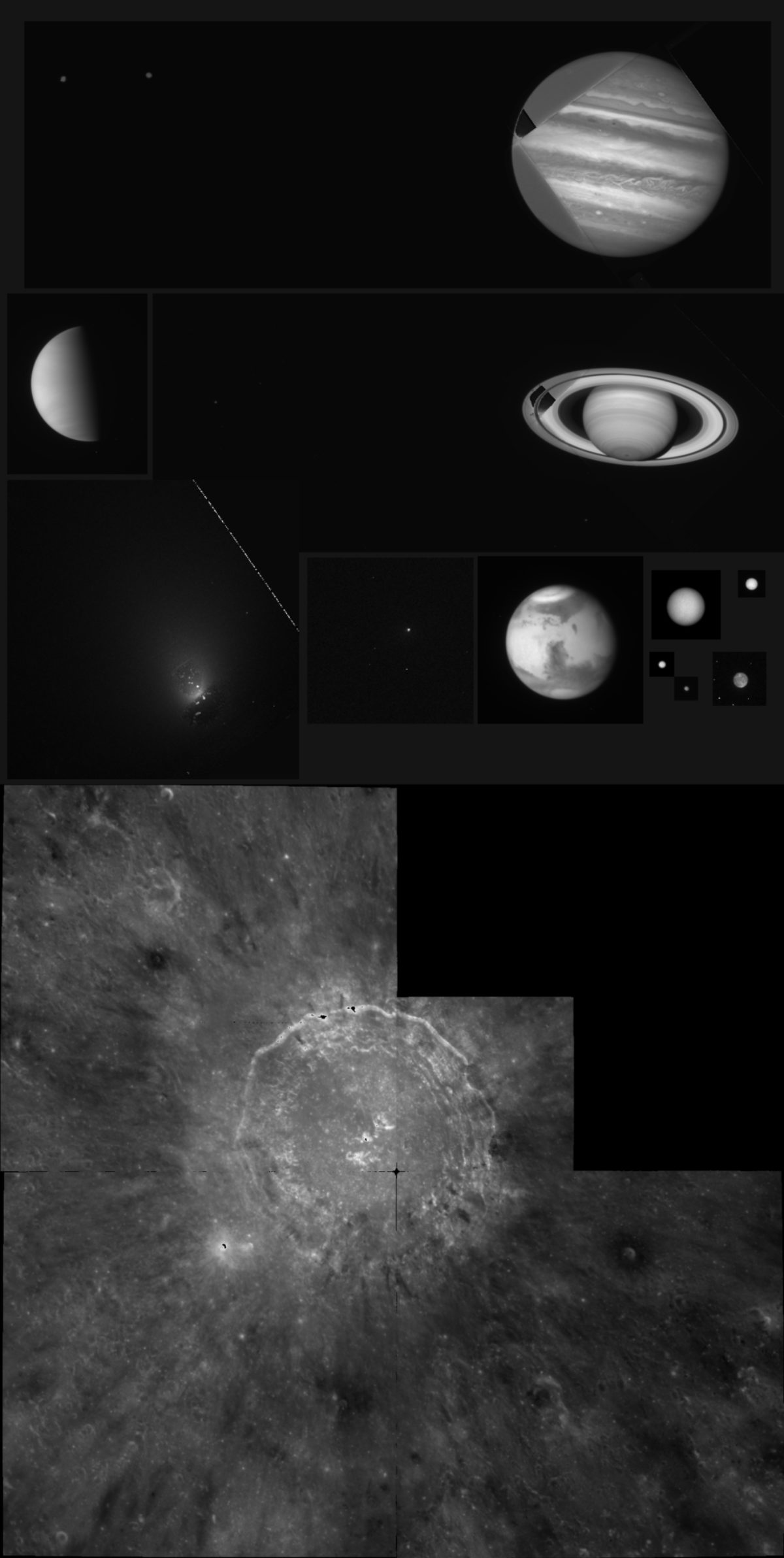

So much data, so little time! I searched on various targets and dug up all kinds of good stuff. Here's a little sampler of the kinds of images that you can find in the Hubble Legacy Archive; I didn't take the time to do any fancy processing, just adjusted the contrast to make things visible. These aren't the best things available -- they're just the random ones I clicked on as I was wandering around the search results table. All of these images are from Hubble's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2; they're taken through a variety of different filters.

Remember that since Hubble is sitting in Earth orbit, objects look relatively bigger if they're closer to Earth and smaller if they're farther away. See how small Neptune is? That's why I didn't even try to dig up any of the images of Kuiper belt objects -- I'd have little hope of figuring out which bright spot within the data is the object being looked at. (You're safe for now, Mike.)

If you want to dive into the Hubble archive yourself, there is a little bit of a learning curve involved in working with the data, but there is also tons of documentation available on the Hubble Legacy Archive website. You will need some kind of software that can read FITS format images. FITS is commonly used by astronomers because it is designed to encode images that contain objects over an incredible range of brightness, from dark little Kuiper belt objects to bright stars, from dark, dusty rings to bright ice giant clouds, all within the same picture. I use the free FITS Liberator plugin to Photoshop provided by the ESA side of the Hubble project, but there are other options out there if you don't have Photoshop.

Sadly, I just don't have the time to really learn how to process these images, so with this post, I am going to have to tear myself away from them. I will have to rely on other amateurs out there figuring things out and sending me pretty pictures to post. But what I can do is tell you what is there to be found in the data set. I sorted the search results on the target field and came up with the following reasonably comprehensive list of targets. (Remember that you need to enter these things with wildcards, as *targetname* in order to produce all of the observations containing each target.) I provide it to you as a map to the hidden treasures within the archive. Now go forth and dig up some pretty pictures!

| alexandra amphitrite any apollo-15 apollo-17 arend aristarchus ashbroo asteroid astrae b2 borrelly bus cabeus-a callisto (also cal-*) camilla eres cernis cg ciffreo clark comet copernicus crocus cybele dione egeria elektra eris eugenia eunomia europa faye finlay flora forbes fringilla ganymede (also gan-*) gehrels giclas glauke | gleason gyptis hale-bopp hartley haumea hebe herculina hermione hestia holmes hyakutake hygiea iapetus ida io irene iris ixion julia jupiter (also jup-*) karin kb1 kbo kearns kojima kopff kushida leda leonos linear logos-zoe lutetia mars massalia mcnaught melpomene minerva nemausa neptune nysa objectx | obj-kbo orcus pales pallas parthenope pluto quaoar reinmuth2 saturn (also sat-*) schaumasse schuster sedna shajn shoemaker skiff sl slew smirnova spacewatch sw swift sylvia tempel tempel-tuttle titan torres triton tuttle uranus urata ursula varuna venus vesta vibilia west wild wirtanen wiseman wolf |

Also there are lots of provisionally designated objects. The provisional designations can take the form YYYYaa#, like 1992qb1 and 2003el61; they may have the form YYaa#, like 99tr11; they may have the form YYYY-aa#, like 2003-qa91; there are some with more complicated number-letter designations starting with j or k; there are provisionally designated comets, like p2010-a2; and some just have 4- to 6-digit numerical designations, like 20108. For these objects, rather than filtering on the target, it may be more productive to filter the search results on the names of the principal investigators who most often do these kinds of observations: Brown, Noll, and Grundy are among the most prolific ones. | ||

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth