Emily Lakdawalla • Mar 12, 2010

Pretty pictures: Europa from Galileo and Voyager

For some reason both Jason Perry and Ted Stryk took it upon themselves to produce new, pretty versions of Jupiter's moon Europa this week, so I'm hereby featuring them! Europa is picturesque and strange both from a distance, as seen by Voyager, and from close up, as seen by Galileo. There's no landscape in the solar system quite like it.

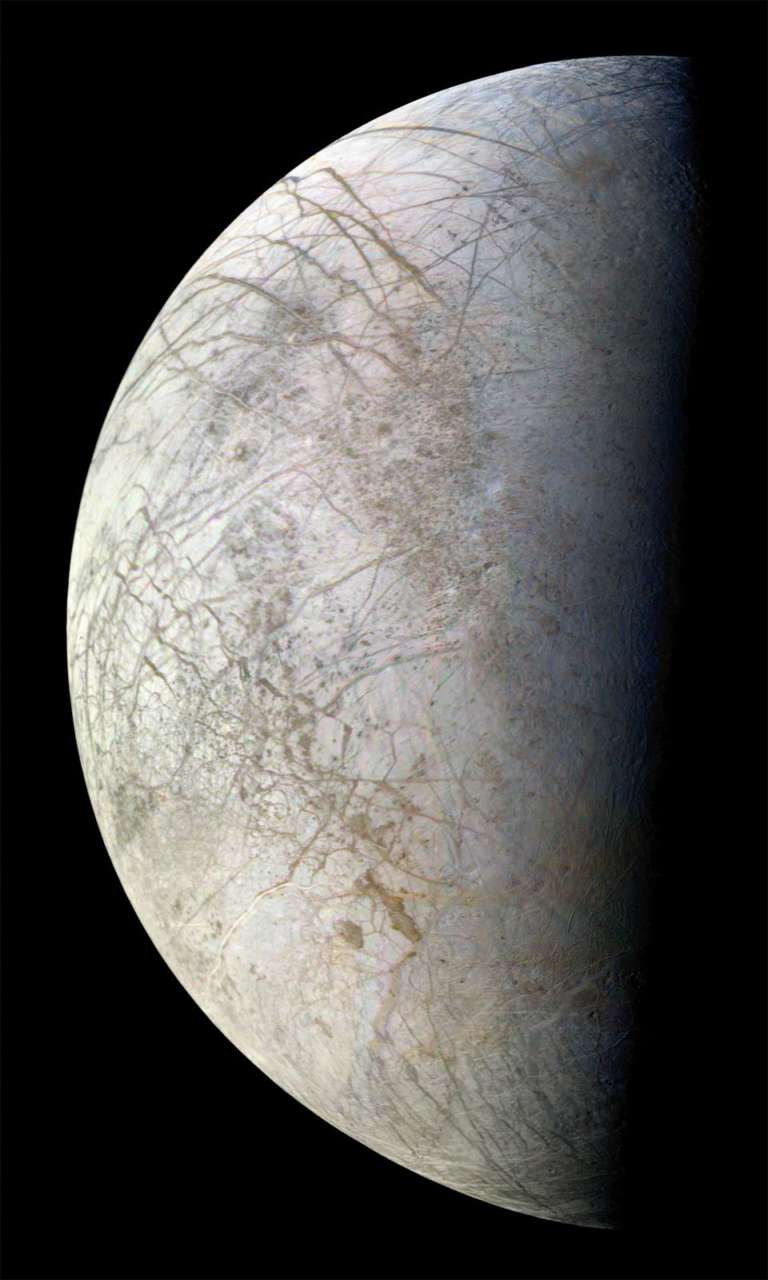

First, a global view, from Voyager 2, produced by Ted Stryk. It is amazing in hindsight to find out that Europa was considered the least interesting of the Galileans before the Voyagers flew by, though it's not hard to understand why: Ganymede and Callisto are much, much larger, while close-in Io was known from telescopic studies to have a surface of bizarre composition. Europa was bright but the tiniest of the four, so when hard choices had to be made about which would get close passes, it was Europa that wound up being farthest from the two Voyagers.

But oh, what they saw from that great distance! Here's what Europa looked like when Voyager 2 saw it from a distance of a quarter of a million kilometers:

What were those lines? And where were the impact craters? Europa became a maddening mystery -- what had happened to erase the impact craters, and what did those linear features look like up close?

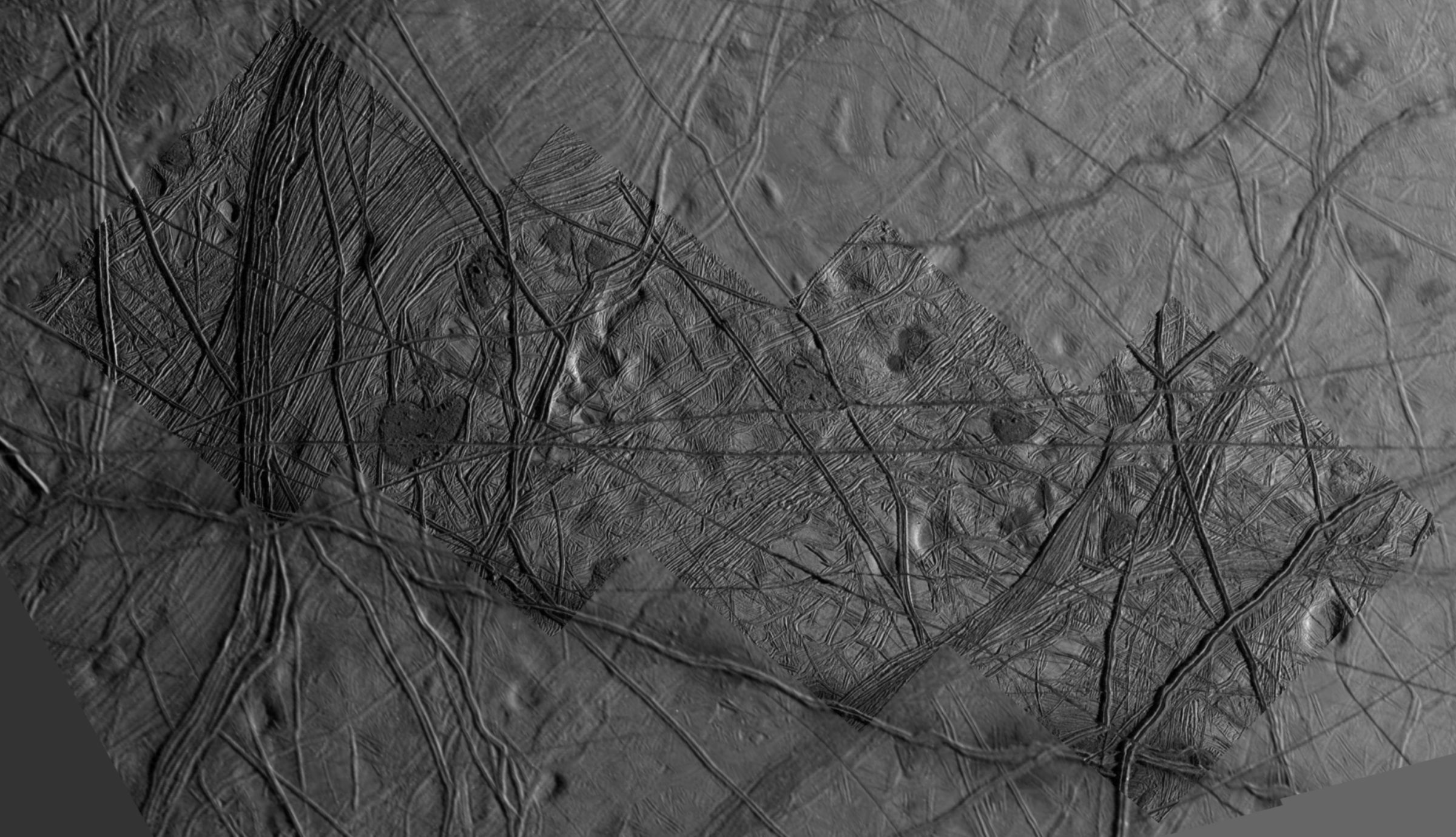

The Galileo mission delivered an amazing quantity of data (considering its transmission woes) in an attempt to answer that question. Jason Perry has lately reprocessed seven of Galileo's high-resolution mosaics. Most of the high-resolution views were targeted so that the landscape was seen lit with glancing twilight so as to highlight the surface topography. Not only did Galileo reveal the structure of those ridges, it revealed that there structure was incredibly diverse. In some places they were single ridges; in many places, paired ridges; in some places there were wide lanes of grooves; and they criscrossed in an incredibly complex web of crosscutting relationships, presenting the kinds of puzzles that make structural geologists drool. This is just one of those seven mosaics; most of them are much larger, and are well worth exploring at Jason's blog here, here, and here.

When I was at Brown, from 1998 to 2000, most of the more senior graduate students were paid for by the Galileo mission. There was one imaging lab that contained three or four PowerMacs for examining the images and an enormous table on which were strewn printouts more than a meter wide and sometimes two meters long of these Galileo mosaics. They were not what I was working on -- my work was in an adjacent lab that housed cabinet after cabinet of Magellan photomaps -- but I frequently stopped in to the Galileo lab to pore over these amazing closeup views of Europa. They were so puzzling, both fun and maddening. And the highest-resolution images never quite landed where the imaging team had planned them to; always, the feature of interest, like Rhadamanthys Linea in the mosaic above, seemed to fall just off the edge. It was frustrating, but one thing about Europa is that no matter what part of it you photograph, there are fascinating things to look at!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth