Emily Lakdawalla • Feb 25, 2010

Welcome news on DSN upgrades

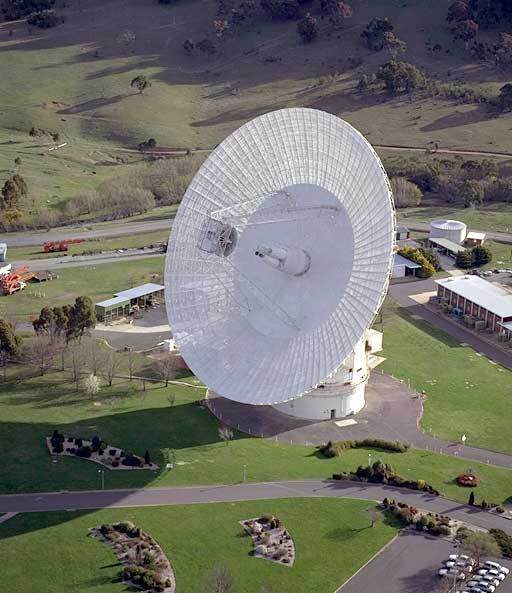

I've written before about a serious problem looming for planetary exploration: the aging infrastructure of NASA's Deep Space Network (DSN). It is through the giant radio dishes of the DSN -- 34 or even 70 meters across -- located in California, Spain, and Australia that we send orders to our distant spacecraft, and receive the volumes of data that they return to Earth. Missions to close destinations like the Moon don't need the DSN; Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, for instance, sends its Terabytes of data through a dedicated 18-meter-diameter antenna in New Mexico. But everything that travels beyond Earth orbit has to compete for precious time on those great DSN antennas.

And those antennas are getting old. The greatest of them, the 70-meter dishes, are around 40 years old. DSS-14 in Goldstone was built in 1966; DSS-43, in Canberra, in 1972; and DSS-63 in Madrid in 1974. The 70-meter dishes are unique assets; when one of them is taken offline for maintenance, it leaves the most distant missions high and dry for some part of the day. And even if they were in perfect condition, they are becoming obsolete. They communicate with spacecraft only in longer-wavelength X and S radio bands and cannot be upgraded to the shorter-wavelength Ka radio band that is planned for use on future deep-space missions in order to multiply the amount of data that they can return to Earth by more than a factor of ten over previous deep-space missions.

So I was very happy to see today's press release from NASA, announcing that they were breaking ground on three, count them, three new 34-meter-diameter "beam wave guide" dishes at the DSN station in Canberra, Australia, which will be capable of operating in the Ka band. The "beam wave guide" part refers to five mirrors that bounce the radio signals from the dish down to a below-ground electronics room. So when these things need maintenance, the maintenance is performed inside a climate controlled, below-ground room rather than in the open air at altitude on an enormous dish -- something that will make maintenance and upgrading faster, easier, and cheaper. The 34-meter antennas can be used in concert, as an array, to substitute for a 70-meter antenna; Cassini already does some of its communications using arrayed 34-meter antennas. Construction of the three new antennas is expected to be complete in 2018.

Why are all three new antennas being built in Australia? Here's two slides from a February 2009 presentation by DSN program manager Michael Rodrigues (PDF format) that illustrate why this is necessary.

It's not just that Canberra has the fewest 34-meter antennas. Look at that little graph on the second slide: it shows you where the outer planets appear on the sky through the rest of this decade. Everything is south of the equator, so southernmost Canberra is going to be the one in the best position to communicate with them. Just Cassini and New Horizons can probably eat up most of Canberra's available capability.

Infrastructure upgrades are never sexy projects; it's like replacing a highway bridge instead of building a new sports stadium. But the DSN antennae are our bridges to our robotic spacecraft; it would be all too easy to take the DSN for granted until we wake up one morning to discover that a catastrophic failure has rendered us unable to get hard-won data back from space. I am sure that today's announcement covers just one line item from a whole laundry list of upgrades that are needed at the three DSN stations. I'm not exactly sure how to advocate for better support of the DSN, except by writing about it here.

To all the folks who keep those giant dishes running, a hearty thanks! Without you we'd never be able to see the distant wonders of our solar system.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth