Emily Lakdawalla • Dec 24, 2009

Planetary Society Advent Calendar for December 25: Double planet

To those of you who celebrate the holiday, merry Christmas! I hope Santa was good to you. I have just completed my first real tour of duty as Santa (at previous Christmases, Anahita was too young to be indoctrinated into the Cult of Claus, but things are different his year). Milk and cookies were delicious, if I do say so myself.

"Real" advent calendars for Christmas ended yesterday, on December 24, leading to a fun Christmas day but then a pretty low week between now and New Year's Eve. Don't fear; this advent calendar runs by my rules, and my rules say it'll keep going until the New Year. So let's move right along, opening presents every day until January arrives!

For a Christmas present, I'm giving you not one but two solar system bodies today -- Earth along with its companion, the Moon, to some, a "double planet". Our Earth, with its climate moderated by vast, planet-encircling blanket of liquid water, is the gift that has permitted life not only to originate (perhaps multiple times), and evolve, but also to survive for more than four billion years. No matter what happens to our planet in the near or distant future, human-caused or externally imposed, life should continue to hold on here, even if it's only unicellular life buried within the crust, until the Sun is a cold, dead cinder. Now that life has been established here, its tenacity continues to astound scientists. Every year people discover stranger and more forbidding environments in which life thrives (or, at least, survives).

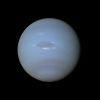

As for Earth's binary companion, inhospitable to life as the Moon is, we now know that it is, in part, responsible for the constancy of climate that allows life to thrive here. Unlike most moons in the solar system, it is massive enough with respect to its planet that it exerts important effects on our planet's orbital properties: in particular, the Moon prevents Earth's axial tilt from wandering too far from its present value. Our tilt gives us seasons that are noticeable to be sure, especially now, near the solstice. But without the Moon, at times during Earth's history the pole would have been nearly upright (a tilt of 0°), and at times nearly parallel to our orbital plane (a tilt of 85°), giving us seasons as extreme as those of Uranus.

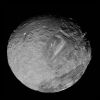

The data for the image below was captured by Galileo as it flew past Earth its second time, on December 8, 1992. It has been re-processed by Gordan Ugarkovic to appear similar to what the human eye would see. It's actually just one frame from a beautiful animation, posted below.

Here's the animation. I think my favorite detail is the specular reflection off of the ocean -- it's diffuse as the animation opens because the water in the Pacific off of Australia's northeast coast was apparently rough that day, but it's starlike and brilliant when it emerges into apparently smoother waters off the west coast. Those of you who haven't ever processed Galileo images cannot possibly appreciate how challenging this must have been to assemble into such a beautiful product. The original data had noise, data dropouts, serious underexposure of the Moon, and all kinds of other problems, even before you consider the difficult work of assembling three-image sets taken sequentially through different-colored filters as Earth was rotating and Moon moving. I thought it was a great Christmas present to get this thing assembled, and I wanted to share it with you!

Each day in December I'm posting a new global shot of a solar system body, processed by an amateur. Go to the blog homepage to open the most recent door in the planetary advent calendar!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth