Emily Lakdawalla • Sep 25, 2009

The "Water on the Moon" Hoopla, Part 1: There's water on the Moon!

For a couple of weeks now, I've been hearing rumors about an upcoming announcement concerning Chandrayaan-1 Moon Mineralogy Mapper ("M3") discovery of "lots of" water on the Moon. On Tuesday, September 22, NASA announced that there would be a press briefing on Thursday, September 24, about "new scientific findings" from "national and international space missions" to be published in the Friday edition of Science magazine. But before the briefing took place, the rumors apparently got prominent enough and specific enough that Science lifted the embargo on what turns out to be three peer-reviewed papers concerning water on the Moon. I got a hold of the papers on Wednesday evening but didn't have time to write about them until now.

Before I start getting lost in the details, here's the big picture:

Got it? Here's the full story. As I wrote it got so long that I decided it'd be easier to digest if it was split into chunks. So this blog entry deals only with the story of the detection of the water (points 1, 2, and 3 from my list above). In a later blog entry I'll get to the story of how much water, in what form, and how it behaves on the surface of the Moon.

Let's begin with the biggest paper, which appears to have started it all, and that's the Carlé Pieters and a billion coauthors' one, titled "Character and Spatial Distribution of OH/H2O on the Surface of the Moon Seen by Chandrayaan-1." It details the results of the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (also known as "M3" which its scientists speak as "M-cubed"), a NASA-built instrument on India's lunar orbiter Chandrayaan-1. Chandrayaan-1 entered orbit on November 8, 2008, and operated for about ten months, until contact was abruptly lost on August 27.

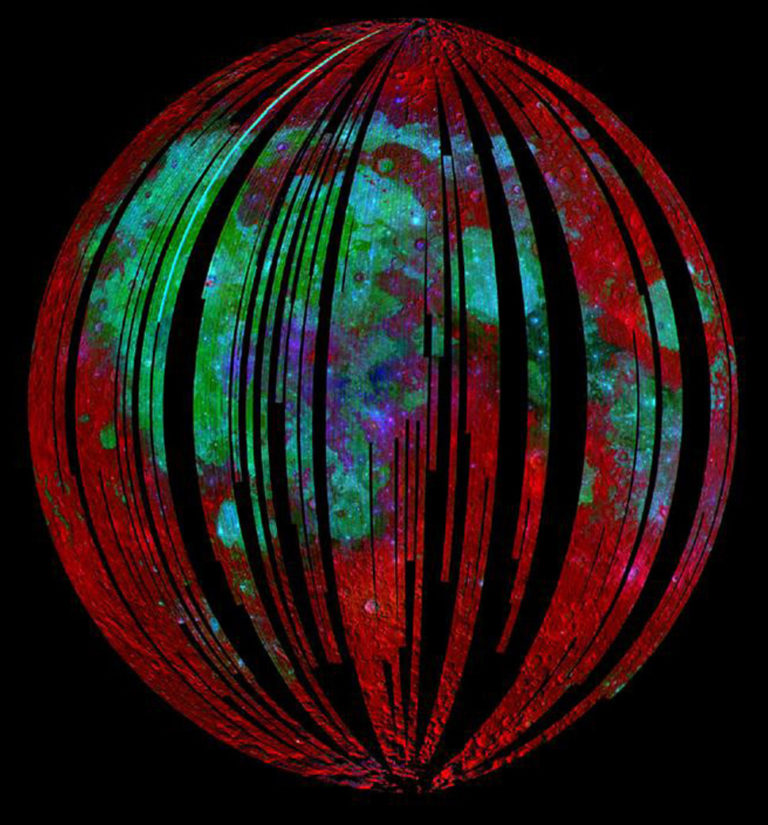

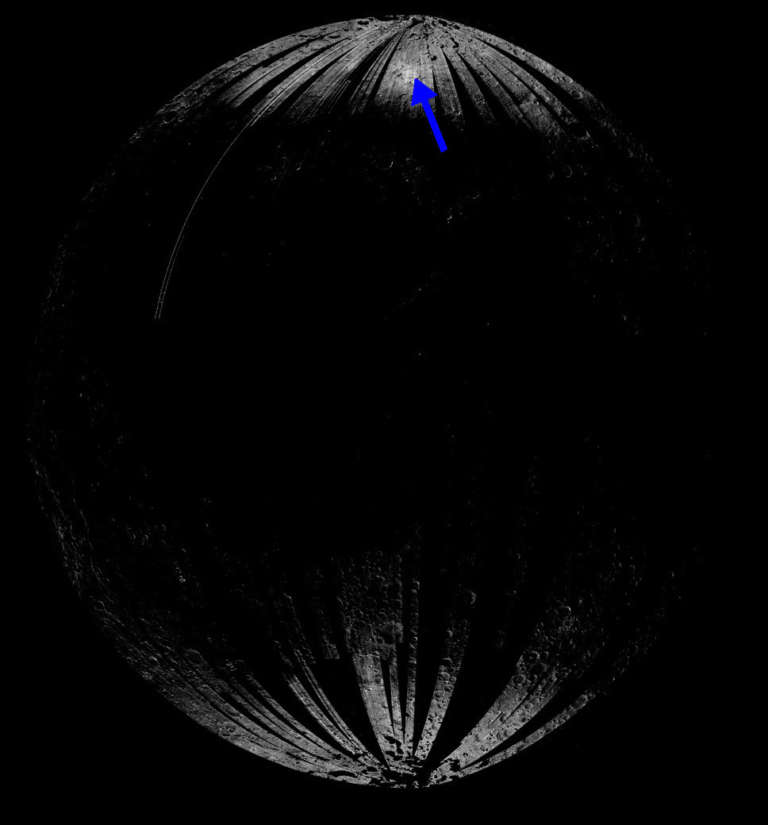

Here is what the M3 data coverage on the lunar nearside looks like after the 10-month mission of Chandrayaan-1. M3 seems to have acquired a pretty complete data set on the Moon despite Chandrayaan-1's short life, mapping 90% of the lunar surface.

his version of the M3data represents the same information you'd get from a camera photo or your own eyes -- it shows you how bright the surface is.

But M3 is an imaging spectrometer, not a camera. Imaging spectrometers usually capture images of planetary targets at lower spatial resolution than cameras (that is, the images look coarser, more pixelated), but they have higher spectral resolution, meaning that at each pixel in an image, they have data on how that spot on the target reflects light at many different wavelengths. Here's a psychedelic, random walk through the M3 data, intended to show you how much richness there is in the color information it gives us about the Moon. (Check it out on Facebook for HD resolution.)

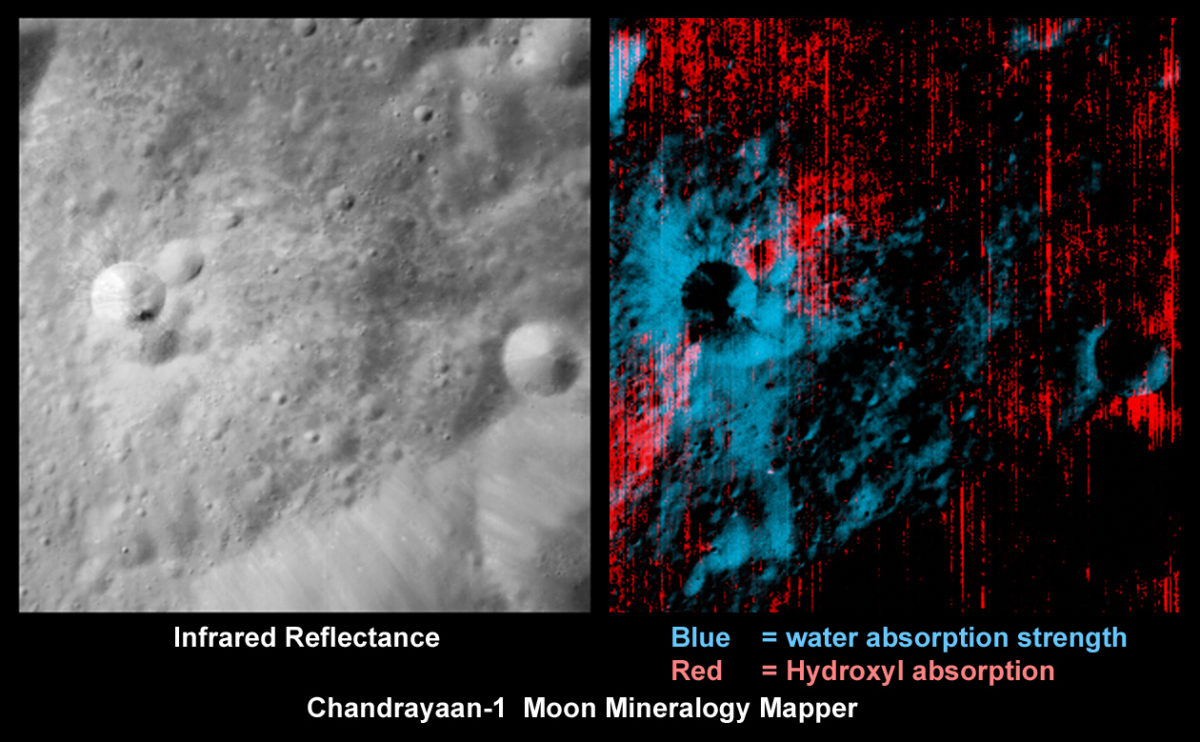

Here's an example of the kind of view scientists were hoping to get from M3. It's a processed version of the data that reveals information about the minerals that make up the rocks and soil of the Moon's surface.

The caption to that image may already cause trouble for most readers. What are "spectra," and what's an "absorption feature?" So let me digress from the Moon for a moment to show you an example of some spectra from a totally different place, comet Tempel 1. These were taken by the infrared spectrometer on Deep Impact, which will figure into the lunar water story below.

The X axis shows wavelength from 2 to 4.5 microns, all near-infrared. The Y axis is radiance; the higher the peaks, the more photons were measured at that wavelength.

The red line represents the spectrum of comet Tempel 1 taken as Deep Impact approached the comet nucleus. It's very flat with very few features in it. This is typical for bodies that have been sitting in a vacuum exposed to the solar wind for a long time. It's difficult to learn much about a body from a spectrum that looks like that. One thing you may have noticed though is that the spectrum trends "uphill" toward the right. That's because it's essentially a black body, radiating dully in the thermal infrared; this black body thermal radiation would come to a peak somewhere to the right, off of the graph.

To figure out what Tempel 1 was made of, the Deep Impact mission crashed a heavy impactor into it and then looked at it again with its spectrometer. The green line represents the spectrum of the comet and ejecta after the impact. Each peak and valley is a "spectral feature," which a spectroscopist can read like a book. Peaks at certain wavelengths, dips at others, even the shapes of peaks, can identify certain molecules or atoms. The complicated set of peaks and dips between 2.5 and 3 microns is a diagnostic indicator of the presence of water in one form or another in the comet.

The blue line is a first attempt at a "model fit." The "model" consists of a weighted average of spectra of the individual component materials that one would expect to find in the comet.

Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UMDSo an "absorption feature" is a dip in a reflectance spectrum, a sort of fingerprint of an element or compound seen on a planetary body. With me so far?

M3 is neither the most nor the least capable imaging spectrometer I've ever read about. According to the National Space Science Data Center entry on it, it was intended to acquire a global map of the Moon with a spatial resolution of 140 meters per pixel and a spectral resolution of 30 nanometers, sampling 86 different slices of the electromagnetic spectrum from 430 to 3000 nanometers (which is from blue through the entire visible light spectrum to near-infrared). That last sentence contained a lot of numbers. The important number to remember is the 3000-nanometer, or 3-micron, maximum wavelength that M3 can see.

According to the Pieters et al. paper, "a feature near 3 micrometers was seen in several areas of the first returned sequences of M3 data. As global data accumulated, it became evident that this feature is observed systematically across the Moon." If a spectroscopist sees an absorption feature at a wavelength of approximately 3 microns, their first thought is "water." But when a spectroscopist thinks "water," they're not thinking of the same thing that most people are. The 3-micron feature indicates the presence of an oxygen atom bonded to a hydrogen atom. This most commonly arises in one of two chemical situations: it can be the kind of water you're thinking of, a molecule consisting of two hydrogens covalently bonded to an oxygen. But it can also be a "hydroxyl group," a negatively charged ion consisting of one oxygen and one hydrogen, written as OH-. Hydroxyl ions typically come from water molecules, but they are not, themselves, water; they may well be a part of a solid mineral. Many clay minerals, for instance, contain hydroxyl groups in their crystal structure. The absorption feature due to hydroxyl is strongest at a wavelength of 2.8 microns. Molecular water produces absorption features at slightly longer wavelengths, going out to 3 microns and beyond.

The M3global map of the Moon came together, and it displayed a systematic trend:

That 3-micron absorption feature due to water or the hydroxyl ion was strongest at high (polar) latitudes, and did not appear to have any relationship to the underlying distribution of minerals across the Moon -- there was no correlation to whether the underlying rock was the (relatively) bright feldspar-rich highlands or the dark pyroxene-rich basalts that make up the lunar maria. They did note that the strongest absorption feature was visible in a couple of fresh craters in the highlands. That's no surprise; absorption features of any kind are usually stronger where the rocks are more freshly broken (just as in the Deep Impact Tempel 1 spectrum above, which was featureless before the impact and full of great spectral detail after the impact broke a fresh hole into the comet). On the Moon, space weathering processes, where protons from the solar wind bombard exposed rocks and steal oxygen from lunar minerals, leave behind tiny, tiny ("nanophase") blebs of iron that flatten lunar spectra, hiding their features.

At first, the M3 team didn't believe that the water absorption was real, as Carlé Pieters said during yesterday's briefing. "We, like most other teams before us, immediately assumed, 'this is calibration error. This is not possible. The Moon doesn't do this.'" The problem is that M3 and all other spectrometers that have been sent to space were assembled on Earth, and on Earth, water is EVERYWHERE, as M3 team member Roger Clark explained. "Every spacecraft that is launched from the Earth, when it's made in the lab, there's so much water and it's such a sticky molecule that it's all over the spacecraft. Spectrometers can see that water, so it's quite a challenge to calibrate the spectrometers so we're not seeing water everywhere."

Roger Clark is on the Chandrayaan-1 M3 team, but he is also a member of the Cassini Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) team. On VIMS Clark has been dealing with water as a calibration problem for a decade. Cassini gathered some data on Earth and the Moon during its 1999 flyby for calibration purposes, but that wasn't enough. "We had no other calibration data until we were approaching Saturn in 2004, when we started looking at stars and the Sun. It took us quite a long time to calibrate out the water. We were actually seeing stars with water in them." Stars just don't have water in them, so any water that Cassini saw in a star must be due to an error in calibrating the VIMS instrument that arose from its birth on the water-rich Earth.

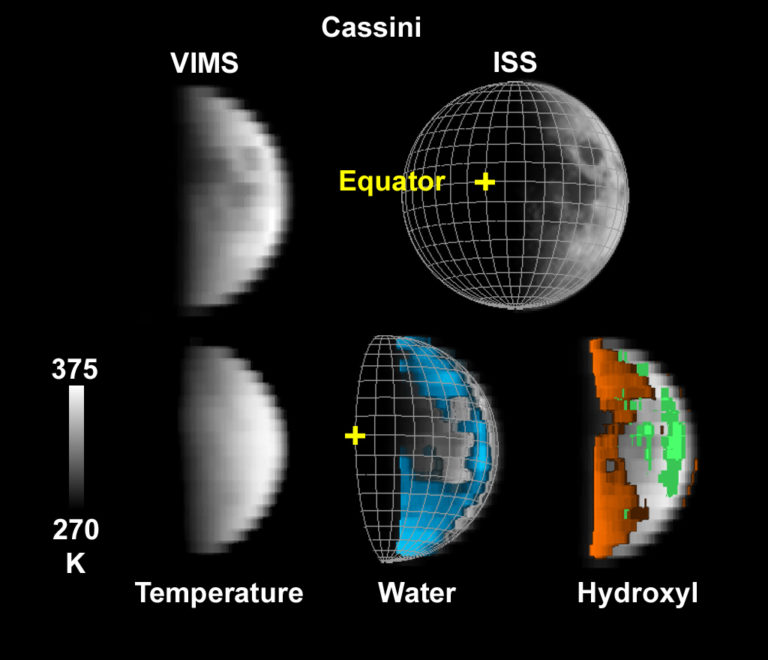

The Cassini VIMS team has been working assiduously on their calibration issues though. So it was natural for Clark, as he examined this apparently crazy result from Chandrayaan-1, to apply their new calibration procedure to the Earth-Moon flyby data from August of 1999. Lo and behold, VIMS saw exactly the same thing that M3saw -- and more:

VIMS was able to see the feature across more of the lunar surface because its detection capability extends farther out into the infrared than M3's does. M3stops at 3 microns, right in the middle of those interesting water features -- no one sending a spectrometer to the Moon would have thought that would be important! -- and at that wavelength, there also begins to be a problem with the Moon's thermal emission where the Sun warms it, which acts to hide the water feature from view in the Moon's warmer equatorial regions. VIMS was designed to study the icy worlds of the Saturn system, so its detectors reach out to 5.1 microns, well beyond all those interesting water features, and far enough to make it easier to detect a subtle signal from water even when it's complicated by the contribution from thermal radiation. Clark showed a comparison of M3and VIMS spectra that show good agreement between the two spectrometers up to 3.0 microns, and how VIMS sees the water features out to 3.2 microns.

So the VIMS data seemed to show the same crazy result, that there were detectable spectral features from water across the Moon. Carlé continued the story during yesterday's press briefing: "As Roger brought in the VIMS data, and as M-cubed data accumulated, this was something we could not ignore. We spent months trying to disprove this. We tried everything. We could not find anything wrong with either our data or the VIMS data. At that time we decided we should start writing."

As they began writing their papers, Carlé said, another M3 science team member, Jessica Sunshine, reminded them that Deep Impact was planning on pointing its spectrometer at the Earth-Moon system for calibration purposes in June of 2009. Like Cassini's VIMS, the spectrometer on Deep Impact was designed to look at water-rich bodies, so extended longer into the infrared than M3 did. And it so happened that Deep Impact's view of the Moon was going to be onto its north pole, the region where M3 saw the strongest water absorption feature.

So they waited for Deep Impact's lunar flyby, and then Jessica worked for a quick turnaround of the calibration of the data from the Deep Impact team. And here it is, along with some earlier calibration data that measured an equatorial region on the Moon.

There you have it. Three different instruments on three different spacecraft have all detected the presence of an absorption feature due to water on the surface of the Moon, with a stronger signal from the poles than from the equator. There is no doubt about it -- there is water in lunar rock. This is a Really Big Deal. It is the first time that water has been detected across widespread regions of the Moon. This isn't like the endlessly repeated "discovery" of water on Mars. This is a totally new result. For human exploration purposes, we've long hoped we could find evidence for water on the Moon and now we have.

BUT. There's always a "but." Now there are questions to answer:

- How much water are we talking about?

- What form does it take? Is it incorporated into lunar minerals or is it just hanging around as actual water molecules?

- Where does it come from?

- And can we actually use it as a resource for human exploration of the Moon?

I deal with these questions in the next post.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth