Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 13, 2009

The Jupiter Impact

I've received a half-dozen emails asking why there hasn't been anything on the blog yet about the Jupiter impact. The answer: there's only one of me! But now I'm finally getting to the story, nearly a month after it happened. There is one advantage to being so late to the party: I can tell you about what's happened since the discovery.

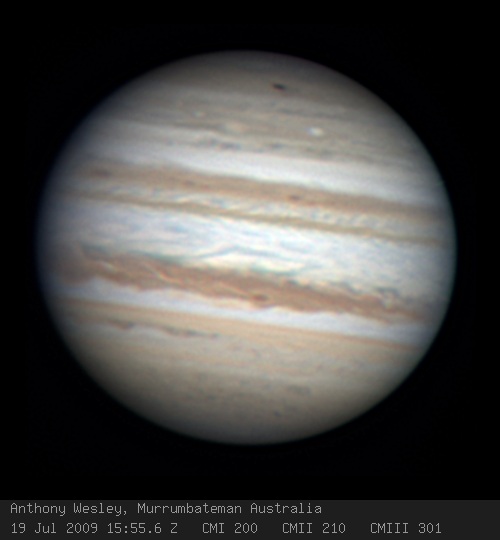

On July 19, 2009, fifteen years almost to the day after comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 struck Jupiter, an amateur astronomer named Anthony Wesley pointed his home telescope (located in Murrumbateman, New South Wales, Australia) at Jupiter. Wesley's setup looks serious but I'm sure there are plenty of other amateurs out there with scopes just as spiffy; Wesley was in the right place on Earth at the right time to be the first one to the discovery.

When I came back to the scope at about 12:40 am [14:40 UTC] I noticed a dark spot rotating into view in Jupiter's south polar region [and] started to get curious. When first seen close to the limb (and in poor conditions) it was only a vaguely dark spot, I thought [it] likely to be just a normal dark polar storm. However as it rotated further into view, and the conditions improved I suddenly realised that it wasn't just dark, it was black in all channels, meaning it was truly a black spot.My next thought was that it must be either a dark moon (like Callisto) or a moon shadow, but it was in the wrong place and the wrong size. Also I'd noticed it was moving too slow to be a moon or shadow. As far as I could see it was rotating in sync with a nearby white oval storm that I was very familiar with - this could only mean that the back feature was at the cloud level and not a projected shadow from a moon. I started to get excited.

It took another 15 minutes to really believe that I was seeing something new - I'd imaged that exact region only 2 days earlier and checking back to that image showed no sign of any anomalous black spot.

Now I was caught between a rock and a hard place - I wanted to keep imaging but also I was aware of the importance of alerting others to this possible new event. Could it actually be an impact mark on Jupiter? I had no real idea, and the odds on that happening were so small as to be laughable, but I was really struggling to see any other possibility given the location of the mark. If it really was an impact mark then I had to start telling people, and quickly. In the end I imaged for another 30 minutes only because the conditions were slowly improving and each capture was giving a slightly better image than the last.

Eventually I stopped imaging and went up to the house to start emailing people, with this image above processed as quick and dirty as possible just to have something to show.

Anthony Wesley

Discovery image of the 2009 Jupiter impact

This photo of Jupiter was captured by Anthony Wesley on July 18, 2009 at 15:54 UTC from a home observatory at Murrumbateman, New South Wales, Australia. A black mark near the top of the image marks the location of the impact mark discovered by Wesley near the south pole of Jupiter.A corroborating observation of the new feature came 10 hours later from amateur astronomer António Cidadão, who photographed Jupiter in the near-infrared (specifically, at 889 nm, a "methane absorption band") and found it to appear bright, meaning that it was located high in the atmosphere. You can see a small version of his image here; I wasn't able to locate a higher-resolution version.

Another 10 hours later -- nearly a full Earth's rotation -- Jupiter came into view from Hawaii, where professional astronomer Glenn Orton just happened to be observing Jupiter using the Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea. "We were extremely lucky to be seeing Jupiter at exactly the right time, the right hour, the right side of Jupiter to witness the event. We couldn't have planned it better," Orton said in a JPL press release. Their image was taken at a wavelength longer than Cidadão's, 1.65 microns. (1.65 microns is also known as "H band" and is the wavelength of a "window" through Earth's atmosphere, where water vapor is not strongly absorbing.) According to the release, the wavelength is "sensitive to sunlight reflected from high in Jupiter's atmosphere." In other words, the bright spot indicates the presence of a new something, loacted in the uppermost atmosphere. In this image, south is at the bottom.

NASA / JPL / Infrared Telescope Facility

Jupiter as seen by the Infrared Telescope Facility, July 20

Observed at a wavelength of 1.65 microns, Jupiter had a new, bright blemish on July 20. This image was taken about 20 hours after an impact mark was discovered on Jupiter by Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley.The next astronomer who already had time on the right kind of major telescope at the right time of night appears to have been Paul Kalas, who (along with Michael Fitzgerald) was lucky enough be at the Keck II telescope. They were planning to study a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting Fomalhaut, but shifted gears quickly when they read about the impact on the blog of Franck Marchis, another astronomer. They collaborated with Marchis to develop the best imaging plan. Marchis has a lengthy post on what developed, including more images. Among other things, Marchis says they were able to repeat the observations 4 hours later, which allowed them to determine that "there is no additional impact features on Jupiter. So whatever hit Jupiter this time was not a disrupted with multiple fragment comet like Shoemaker-Levy 9."

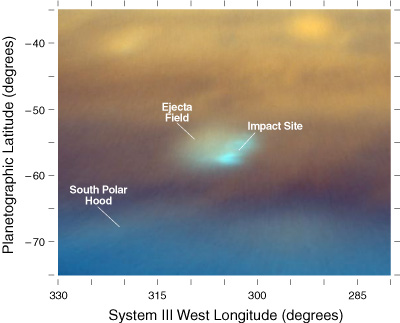

Paul Kalas, UCB; Michael Fitzgerald, LLNL/UCLA; Franck Marchis, SETI Institute/UCB; James Graham, UCB

False color image of the impact site in Jupiter's southern hemisphere.

The data for this image was captured in near-infrared wavelengths including 1.6 and 2.2 microns from the Keck II telescope on July 20, 2009.

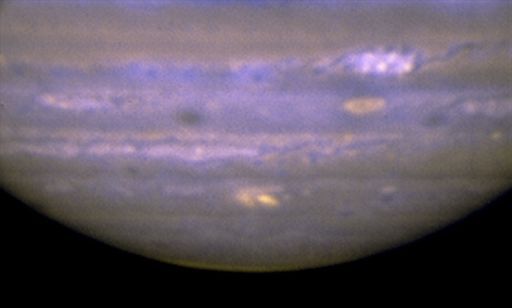

Imke de Pater, UCB; Heidi B. Hammel, STScI; Travis Rector, UAA; Gemini Observatory / AURA

Jupiter from Gemini North, July 22, 2009

The Gemini North telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawai'i, observed the new impact site on Jupiter on July 22 at ~13:30 UT with the MICHELLE mid-infrared spectrograph/imager. The impact site is the bright yellow spot at the center bottom of Jupiter's disk. The image was constructed from two images: one at 8.7 micron (blue) and one at 9.7 micron (yellow).

NASA, ESA, and H. Hammel (Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.), and the Jupiter Impact Team

Jupiter from Hubble, July 23, 2009

The Hubble Space Telescope turned its newly installed Wide Field Camera 3 toward Jupiter on July 23, 2009 to capture this natural color image of the impact feature that was first observed near the south pole on July 18. The impact mark is a dark spot and has been stirred around by Jupiter's atmospheric turbulence.That's the last of the major telescope facilities to have issued releases. Some images from the Very Large Telescope in Chile have shown up at Franck Marchis' blog, though.

All this time, of course, there have been plenty of amateurs pointing their scopes at Jupiter (they now have three good reasons to do so!) The best place I know to check for collected amateur images is spaceweather.com. Here's a shot from discoverer Anthony Wesley dated July 24:

Juan Miguel González Polo, Cáceres, Spain

Jupiter rotation animation, July 24, 2009

This marvelous animation consists of 28 frames captured by amateur astronomer Juan Miguel González Polo of Cáceres, Spain. He explained: "Begins with the Great Red Spot, when the planet was very low over the horizon, and ends when the spot of the impact ocults by one edge of the planet. Covers from 22:22 (U.T.) to 02:52 (U.T.). The images were captured with a LX200 10" Classic (very classic), plus one barlow x2 and a QHY 5C camera. The interval between images is 10 minutes. Each image is the result of the best 250 frames of every video, processed with Registax 5. When appeared the impact I thought I have a dust spot in the camera chip, until I relized that I was seeing the real impact. The composition of the animation was made first with layers in PhotoShop and then with ImageReady. Finally I reduced the composition at 75%."By the 28th, amateurs were reporting the mark to have elongated, developing two distinct lobes. Here's a pretty picture taken by Brazilian Fabio Carvalho on the 29th:

Hans Joerg Mettig / Theo Ramakers / spaceweather.com

Polar projection of amateur images of Jupiter impact

This animation is composed of 13 amateur astronomers' photos of Jupiter taken between July 19 and August 8, 2009, documenting the evolution of the impact mark discovered by Anthony Wesley. It is cropped from a larger view visible here.This is a very difficult question, and I am not sure I can provide a response. It is evident that amateur astronomers are equipped with state-to-art cameras which should allow them to detect these events more often. Because the planetary science community does not have a survey telescopes dedicated to observe the planets (unfortunately), we entirely rely on the contribution of amateur astronomers to detect these impacts. This is also true for detecting supernovae, recording light curves of asteroids and astrometric positions of near Earth asteroids. It is quite possible that over the last 15 years we have missed most of them. The future will tell us the frequency of these events, we need to keep the amateur astronomy [community] around the world motivated to make sure that these Giant planets are often observed, not only for the science, but also for their beauty and for inspiring the young generation.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth