Emily Lakdawalla • Aug 05, 2009

An "amateur" discovers moons in old Voyager images

Voyager 2 took its last images of Neptune in September of 1989, nearly 20 years ago. And unlike more recent missions, Voyager 2's image catalog is of a manageable size; I think it's safe to assume that all of its images have been looked at before, even studied, by at least a few scientists. So you might assume there's nothing new to find in old Voyager images.

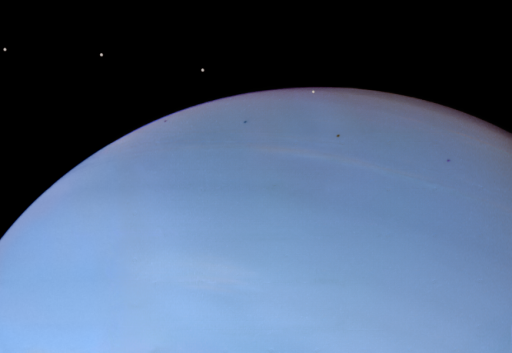

But you'd be wrong. Last week I got an excited email from Ted Stryk, whose work you've seen before on this blog. Ted's a philosophy professor by day but in his free time he pursues his passion for planetary image data, especially really old, gnarly data; Voyager is about the youngest spacecraft whose images he works with on a regular basis. A hunch and some assiduous work led him to spot something no one else had seen before: a tiny eclipse, the shadow of a moon cast on to the planet Neptune. The moon is Despina, 148 kilometers in diameter, originally discovered by Voyager 2 as it approached for the encounter. It got better: Ted realized the shadow was visible in four images captured by Voyager 2 of Neptune at evenly spaced times. And then, amazingly, it got even better: Ted found the moon itself in the frames, and in one image Despina was actually transiting Neptune as seen from Voyager 2 as it cast a shadow on the cloud tops below. Here's a processed version that Ted put together from the component data.

NASA / JPL / Ted Stryk

Despina eclipses and transits Neptune

Despina, 148 kilometers across, is a tiny moon of Neptune located within its ring system and discovered by Voyager 2 in 1989 as the spacecraft approached for its flyby. This view of Despina eclipsing and transiting Neptune is composed of four frames captured nine minutes apart on August 24, 1989 from 20:00 to 20:27 through blue, orange, violet, and green filters. The images were originally captured to study the colors of Neptune's clouds; the fact that Despina and its shadow were visible in the images was discovered by amateur image processor Ted Stryk in 2009.Was it, in fact, seen before? Ted sent his images to Mark Showalter, who runs the Rings Node of the Planetary Data System and is an expert on the dynamics of rings and the tiny moons that orbit within them. Not to mention that he's the co-discoverer, using powerful telescopes, of many tiny moons of outer planets. And not only had Mark not noticed Despina or its shadow in the photos before, as far as he can tell no one else has either, he told me in an email. "I was surprised and delighted by Ted's images. I think it's remarkable for anyone to find something genuinely new in the Voyager images after all these years; they have been scoured over so thoroughly. That being said, it crossed my mind that an atmospheric scientist might intentionally ignore a tiny shadow, and that a satellite scientist would never think to look in an atmosphere image. However, I have contacted several of my Voyager mission colleagues and no one can recall ever noticing or hearing about this before. So I applaud Ted for his sleuthing work. He also produced a really gorgeous image."

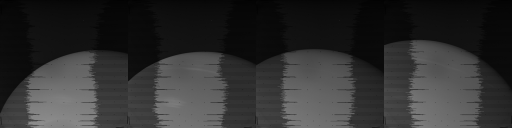

You might wonder what the original data looked like. Here it is; it's marred by truncated lines (which happened on some wide-angle camera shots of Neptune) and is spotted with reseau markings, dots that were painted on the vidicon tube to help the mission scientists correct the images for geometric distortion. Despina and its shadow are roughly the same size of the reseaux, which might explain why they were overlooked before; now that I know the shadows are there, of course, they seem obvious.

NASA / STScI / Larry Sromovsky / processing by Ted Stryk

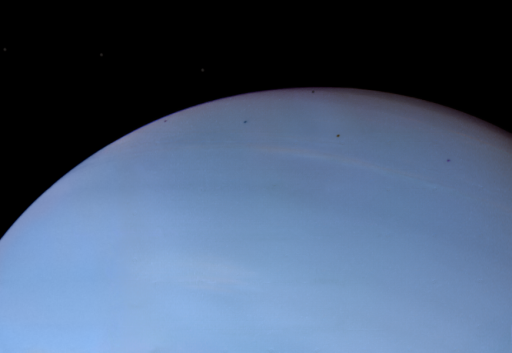

Ariel transits Uranus

The Hubble Space Telescope pointed toward Uranus on July 26, 2006 at about 15:30 UTC to take the images used to assemble this color view of Ariel, the fourth largest of Uranus' moons, transiting the planet's disk. The rings are also faintly visible, as is Miranda, just below the rings to the left of the disk. Another spot to the left of Uranus is a background star. Telescopes across Earth focused on Uranus for a several-year period of intensive study surrounding its December 2007 equinox.The images are a neat find, but they may also be useful. Voyager 2's position in space with time is known pretty accurately, as is the position of Neptune. But the orbits of those tiny moons of Neptune discovered by Voyager are not as accurately known. Having "new" observations of its past position with respect to the positions of known objects may help in refining our knowledge of its orbit.

I'll close this entry with a tiny image of Despina, the best Ted could produce from the few photos that Voyager 2 engineers managed to include in the science plan after the moon was discovered.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth