Jani Radebaugh • Jul 27, 2009

Cassini RADAR continues to gaze at Titan

Hi everyone, I'll be your guest blogger for this week. I'm excited to be chatting with such a smart bunch. Most of my posts will deal with our studies of locations on Earth that resemble those on other planets, usually called "terrestrial analogs", but I couldn't let today pass by without talking about some of the most recent data returned to Earth from a spacecraft. The Cassini spacecraft made its 59th flyby of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, on Friday, July 24, and in the last few hours we have received images from the RADAR instrument in SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) mode. These images take a few hours and some detailed processing to create, unlike many other visible-range images, which is why we look at them sometimes a few days after they are obtained.

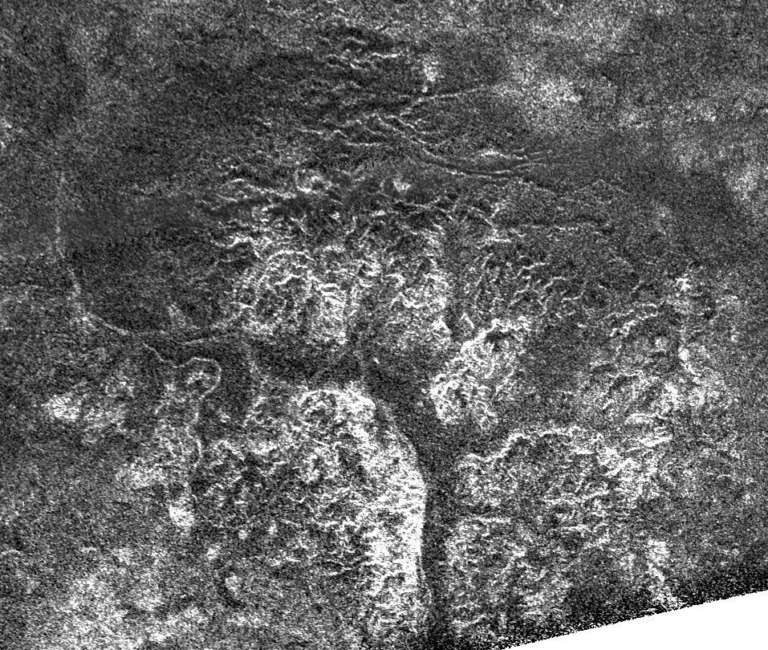

I've seen good discussions of SAR images from Emily and others on this site, so as a refresher, just recall that SAR images are different from visible-range images in several ways. First of all, they are at much longer wavelengths (2.17 cm in Cassini RADAR SAR's case), enabling the instrument to peer down through Titan's thick atmosphere unhindered. Second, they are created by sending and receiving a signal, much like a flash photograph. Third, the greyscale images are created not by albedo (or inherent brightness differences) but by how reflective the surfaces are at the SAR wavelengths. Thus, materials that are highly fractured, have small cobbles, or are pointing directly at the RADAR appear as bright, while surfaces that are very smooth or fine-grained appear as dark. These properties of SAR images give us a lot of information about materials on Titan's surface.

A couple of weeks ago, Zibi Turtle talked a bit about why Titan is so fascinating to us as planetary scientists, and we hope to everyone who sees pictures of it! We find Titan similar in many ways to Earth, more so than almost any other body, even though it is so far from the sun. Given its distance and position within the solar nebula 4.5 billion years ago, Titan's surface is also composed of different elements than the typical silicates (silicon and oxygen-based materials that most rocks are made of) found on Earth's surface. Titan has a crust made probably mostly of water ice, which behaves as a rock at Titan's location, it has an atmosphere nearly the same pressure as Earth's at its surface, and it has a working fluid -- methane -- that rains onto the surface and fills up lakes and rivers, perhaps currently. We think these last two factors, an Earth-like atmosphere and a working fluid, combine to create surface morphologies very similar to those we see on Earth. We see river channels of many different forms and sizes, mountains that look eroded, such as all mountains on Earth, vast fields of sand dunes blown into place by constant winds, and large lakes and seas, some of which are likely currently filled with liquid.

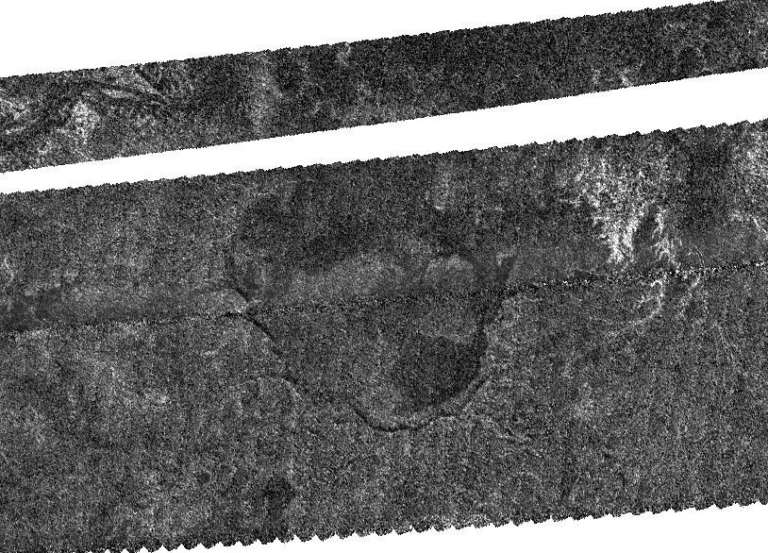

What are we seeing on Titan recently? The latest Titan imaging campaign is a series of "swaths" -- the SAR data is obtained in long, thin strips as the spacecraft moves past Titan -- aimed from the equatorial region just east of 180 degrees (the anti-Saturn point) down to the south polar regions. Beginning with the T55 swath, obtained in May of this year, there have been several such images, T55, T56, T57, T58, and now T59 (T60 will be the final image in this equator -- south pole series, obtained August 7). Each of these has covered new territory and is filling a gap in the imaging of Titan's southern hemisphere, providing us with a more global picture of Titan's geology.

What has emerged from this series of images is that Titan has a fairly latitudinally symmetrical surface, or if you were to start at the equator and walk either north or south, you'd find pretty similar terrains. First you'd be walking through vast fields of sand dunes, then you'd get to some bland, flat regions in the midlatitudes, and finally you'd reach terrains with lake basins, some of them full, near the polar regions. All along the way you'd also pass river channels of various sizes and forms, some of them incising plateaus, and mountains of various forms, some organized into chains. Of course there are some regional exceptions to this pattern, especially in the presence of Xanadu, the large, bright, eroded terrain near Titan's equator, and other similar features.

The new T59 pass shows terrains similar to those seen in the previous equator -- pole swaths. The pass begins too far south to show any dunes, but there are some flat terrains punctuated by randomly spaced mountains, a larger, mountainous region, and long, bright river channels that snake across the terrain. Farther south, there is evidence of more rivers, mountains, dissected plateaus, and mostly empty lake beds. Although these images are not yet released, I've put up a few images from the other recent flybys as examples of what you'll see on the JPL website once the T59 images are released.

We'll carefully study these different landforms in the coming months to help us answer some of the many questions we have for Titan: Why do certain processes occur in their locations on Titan, such as lake formation near the poles? What do the different shapes of mountains and plateaus and the way they erode tell us about the materials that make them up? How do methane and water ice interact to form the many, varied river channels we see on Titan? What do all of these landforms tell us about Titan's origin and history?

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth