Jason Davis • Mar 01, 2018

NASA has a Moon landing plan—sort of

As I continue parsing the White House’s new NASA budget proposal, I’m realizing just how much the Trump administration hopes to spend over the next five years on new human spaceflight programs. I recently wrote about the commercial LEO development program, which will nurture a private replacement for the ISS, and the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, a miniature space station near the Moon. There are also two more programs, both of which focus on humans exploring the lunar surface, that I’ll cover in this article.

To emphasize: this is all new stuff. By my count, the White House proposes to spend $990 million on new human spaceflight programs in 2019, and $5.7 billion over five years. That’s a lot! If you’ve been clamoring for NASA to make a larger shift toward commercial partners and the Moon, this budget is for you—providing Congress goes along with the plan, and the White House follows through in later budgets.

The two lunar surface programs are called Advanced Cislunar and Surface Capabilities (ACSC) and Lunar Discovery and Exploration. ACSC is part of the agency’s human spaceflight division, while Lunar Discovery and Exploration will be managed by the planetary science division.

The last time NASA tried to go back to the Moon was during the Constellation program, using an approach that then-NASA administrator Michael Griffin called "Apollo on steroids." Constellation envisioned a large lander called Altair that conceptually resembled the Apollo lunar module. Altair was being developed using traditional NASA contracting models; Northrop Grumman and Johnson Space Center were leading the effort, but Constellation was cancelled before Altair got very far along.

With this new budget proposal, NASA isn’t exactly going full Altair—at least, not yet. Instead, the agency envisions a gradual, stepped approach, where human spaceflight, planetary science, and commercial partners all work together. Like the Obama-era "Journey to Mars" campaign, the details are vague. There’s an overall strategy in place, but if you want to know the date when astronauts will be back on the Moon, and what type of lander they’ll use, you’re out of luck.

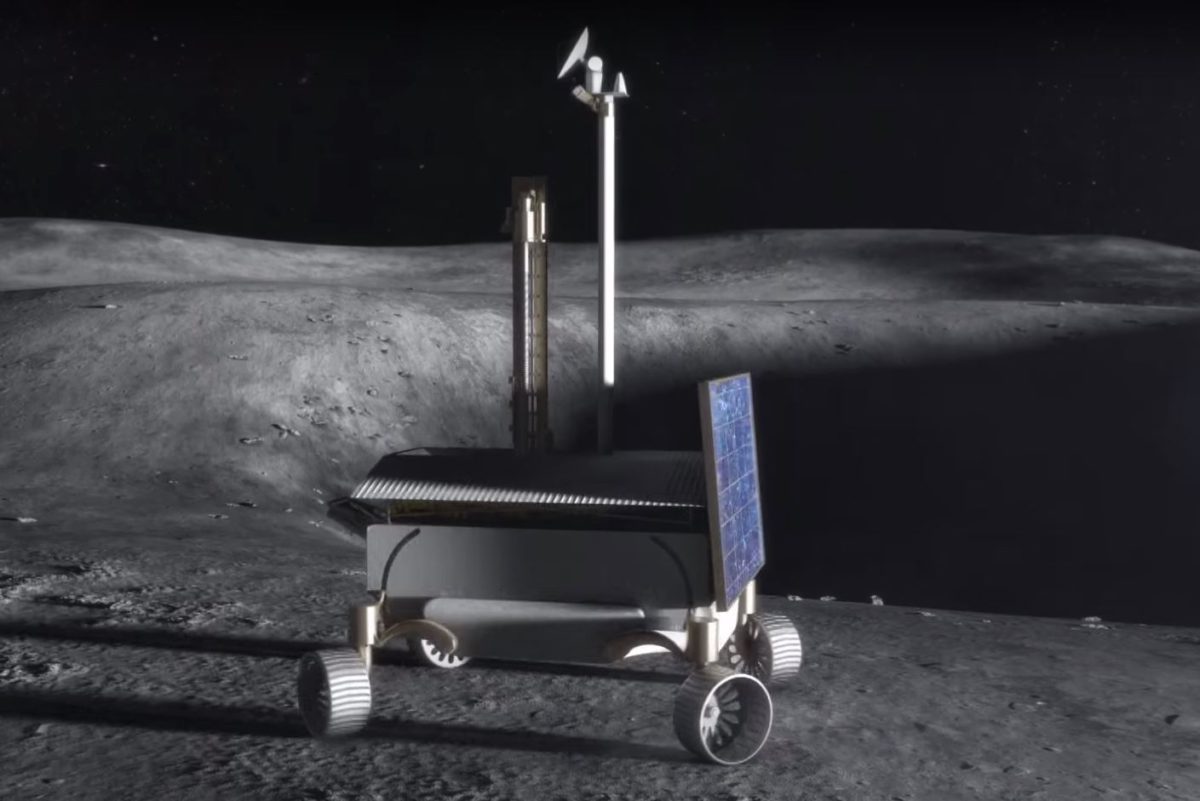

NASA wants to start by helping commercial partners develop and test cheap lunar landing technologies. There are several companies already trying to do this; examples include Moon Express, which was among the groups competing for the Google Lunar X-Prize (the prize will go unclaimed), and Blue Origin, which is promoting its Blue Moon cargo delivery service. NASA would start by funding "risk reduction" studies before awarding contracts for a demo lander in 2019.

Some payload capabilities mentioned for these early landers are 200 and 500 kilograms. As far as I can tell, this is on top of the mass of the lander itself, meaning one of these commercial landers could deploy a rover like Opportunity (185 kilograms). With cheap, reliable surface access, NASA can scout potential astronaut landing sites and deploy in-situ resource utilization experiments, testing to see how easily we can extract oxygen from the lunar soil and use it for things like propellant and water.

From there, work shifts to helping commercial partners scale up the landing technologies to 5,000 or 6,000-kilogram payloads. Assuming once again that this mass capability is in addition to the lander itself, that’s beefy enough to put a crew on the surface; the fully fueled Apollo ascent stage rang in at about 4,800 kilograms. Supplemental cargo flights could deliver human habitats, rovers, and supplies.

Some commercial advocates believe all this will open up a new lunar surface industry. Maybe! The budget specifically says NASA will work with commercial partners to find "opportunities … that would be enabled through regular access to the lunar surface." A lot of forward-thinking folks envision propellant depots, Moon villages, and helium-3 mining, but for now, a new lunar surface industry will exist almost entirely to serve NASA and its potential international partners. The result could be similar to how NASA’s current commercial programs created a new orbital transportation service, which currently only supplies the International Space Station. (There are, of course, ancillary benefits; SpaceX used its NASA revenue to start a revolution in affordable spaceflight.)

What about science? During the Apollo program, science was never the primary goal, and it won’t be the main reason we go to the Moon this time, either. But, as it was during Apollo, there are a lot of potential science benefits—providing they aren’t offset by significant funding shifts from other science programs. (The WFIRST space telescope could be an early casualty of the White House’s shift in priorities to human spaceflight.)

During the first phase of NASA’s return to the lunar surface—tentatively scheduled for the first half of the 2020s—the agency’s planetary science division will be tasked with adding scientific instruments to landers and rovers, using funds from the above-mentioned Lunar Discovery and Exploration program. There’s one line in the budget I find particularly intriguing:

"These payloads and services will address the nation’s lunar exploration, science, and technology demonstration goals, many of which are outlined in the [past two Decadal Surveys]."

The biggest Moon science priority in the past two Decadal Surveys was a sample return from the south pole. The mission is a candidate for NASA’s competitively selected, New Frontiers program, but it keeps losing out to other destinations (most recently, in December, when NASA picked missions to Titan and comet 67P as finalists).

The lunar south pole is also an interesting place for human exploration because water ice may exist in the Moon’s permanently shadowed craters. And at some point, NASA is going to start testing ascent and Earth-return technologies. That makes a south pole sample return mission a great intersection of planetary science and human exploration goals. I predict NASA will eventually do it, outside of the New Frontiers selection process, possibly under the Lunar Discovery and Exploration program. You heard that hot take here first!

I could be wrong (What? Never!). But my colleague, Emily Lakdawalla, noted that during last week's Outer Planets Working Group meeting, the topic of radioisotope power systems came up, and NASA officials mentioned one could be used for a future south pole mission, since you can't rely on solar power inside those permanently shadowed craters. We'll see!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth