Jason Davis • Jan 17, 2018

Let's talk about NASA's latest commercial crew delay

There's an old Calvin and Hobbes comic strip in which Calvin wanders off missing at the zoo, and his Dad, searching for him, says "being a parent is wanting to hug and strangle your kid at the same time." I'm not sure why that strip stayed stuck in my brain all these years, but I can definitely sympathize with the concept, as both a parent and a space fan.

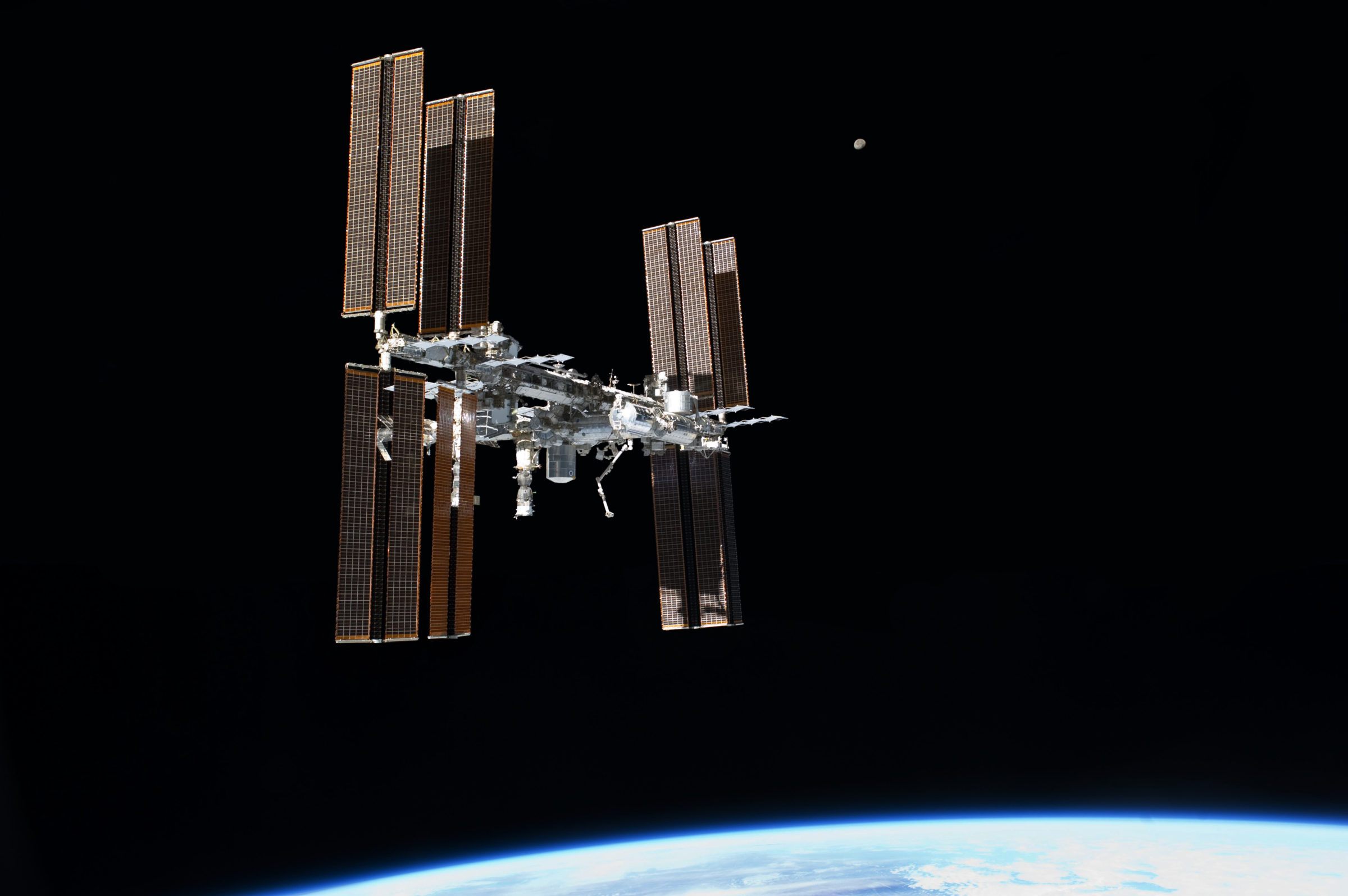

Today, NASA and its Commercial Crew partners faced the music on Capitol Hill, testifying about the latest delay for an already delayed program trying to launch astronauts from American soil for the first time since the end of the shuttle program in 2011. To recap the well-known facts: NASA can currently only access the ISS via the Russian Soyuz. The situation is politically unpalatable, expensive (NASA last paid about $82 million per Soyuz seat), and detrimental to the agency’s human research programs, because there aren’t enough astronauts aboard the station to fully utilize its potential.

For NASA, this has always been an annoyance, and today we learned it could escalate into a full-fledged problem. NASA has only purchased Soyuz seats through Fall 2019, and both Boeing and SpaceX won't be ready to carry out their first crewed test flights until the end of this year. Both company’s vehicles must next be certified before starting regular ISS service, and though publicly that's scheduled to happen in early 2019, internal estimates show it may not occur until December 2019 for SpaceX and February 2020 for Boeing.

Even if NASA panics and immediately buys more Soyuz seats, it takes about three years to build a Soyuz spacecraft, meaning there won’t be extra seats available anytime soon. Bill Gerstenmaier, the associate administrator for NASA's human spaceflight program, could only say NASA was "brainstorming" how to fill a potential gap in 2019.

Other than that, the Congressional hearing was not particularly revealing, as lawmakers from different districts peppered the witnesses with critical or laudatory questions based, for the most part, on parochial interests. What's more interesting is a coinciding Government Accountability Office report released simultaneously with the hearing, and the GAO's Cynthia Chaplain was on hand to discuss the findings. As one of my Planetary Society colleagues puts it, these reports are not exactly page-turners. But if you can stand the dull reading, it's possible to come away from the report wanting to both hug and strangle SpaceX, Boeing and NASA at the same time.

Here's one such example, from a part of the report talking about risks currently being addressed by Boeing:

Boeing is also addressing a risk that during re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere, a portion of the spacecraft’s forward heat shield may reconnect and damage the parachute system. NASA Commercial Crew Program analysis indicates that this may occur if both parachutes that pull the forward heat shield away from the spacecraft deploy as expected. Boeing’s analysis indicates the risk exists only if one of two parachutes does not deploy as expected. If the program determines this risk is unacceptable, Boeing would need to redesign the parachute system, which the program estimates could result in at least a 6-month delay.

Here’s how to parse that, in layperson’s terms: after Boeing's crew capsule finishes plunging through the outer fringes of Earth’s atmosphere, the cover for all the parachute gear pops off. The cover has its own parachutes, which are designed to pull the cover even farther away from the capsule while its main parachutes deploy. (To see this in action on the Orion spacecraft, skip to 5:25 in this video.) There is apparently a risk that the cover could fall back down on the main parachutes, which could tangle or rip them.

I had never, until reading this report, considered this could be a problem. Space is hard! It's a trope, but it's true. So many things have to go right, and it's easy to see how even a minor detail can suddenly cause a six-month delay.

On the other hand: seriously? We've been bringing people back to Earth on parachutes since 1961, and we haven't figured this out? And NASA and Boeing apparently can't agree on how serious of a problem this is?

Here's another example:

SpaceX must close several of the program’s top risks related to its upgraded launch vehicle design, the Falcon 9 Block 5, before it can be certified for human spaceflight. Included in this Block 5 design is SpaceX’s redesign of the composite overwrap pressure vessel. SpaceX officials stated the new design aims to eliminate risks identified in the older design, which was involved in an anomaly that caused a mishap in September 2016. Separately, SpaceX officials told us that the Block 5 design also includes design changes to address cracks in the turbine of its engine identified during development testing.

SpaceX downplayed those turbine cracks in early 2017, after NASA raised concerns. Nevertheless, the company went ahead and modified its turbines to stop the cracks altogether. That seems like a prudent move. Furthermore, by redesigning the Falcon 9's composite overwrap pressure vessels (in layperson’s terms: helium tanks), the company is taking steps to avoid another on-pad explosion beyond merely changing its propellant loading procedures.

On the other hand, SpaceX's "everything all at once" approach (with apologies to my boss) can be maddening. The Falcon 9 Block 5 upgrade includes more than just those two fixes; there are a lot of performance and reliability improvements, including higher engine thrust and improved landing legs. As a result, SpaceX has to demonstrate to NASA the Falcon 9 Block 5 is reliable before humans climb aboard. At the same time, the company is getting ready to launch Falcon Heavy, designing a next-generation launcher and crew vehicle, and planning to colonize Mars. Any other company might reconsider doing so much at once, but not SpaceX.

Both companies say they're on track to conduct their first crewed test flights later this year, but the GAO report shows it's going to be awfully tight. The capsule for SpaceX's flight is still under construction, as is its trunk (service module). Boeing's first crew vehicle is built and integrated, but not the service module. It may be unrealistic to expect both companies to finish and test their crew vehicles, conduct uncrewed test flights, and finally send astronauts into space all in the same year.

Setbacks like this have a tendency to feed the New Space-versus-Old Space narrative; NASA’s Space Launch System was similarly put through the wringer yet again last year. But the only fundamental truth I see here is that space is hard. There are always delays, and the best thing armchair rocket scientists can do is simply enjoy the pageantry and wait for what happens next.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth