Andrew Jones • Dec 19, 2017

A closer look at China's audacious Mars sample return plans

China is making steady progress on a proposed mission to bring a piece of Mars back to Earth in the late 2020s.

The project would be a massive undertaking. But the plans appear serious, and if successful, the mission could result in major scientific discoveries and tremendous prestige—especially if NASA's plans for a similar mission don't get off the ground.

China's space capabilities and ambitions have been growing rapidly in recent years. The country successfully launched two small space stations into Earth orbit and visited them with astronauts, while making rapid advances in robotically exploring the Moon.

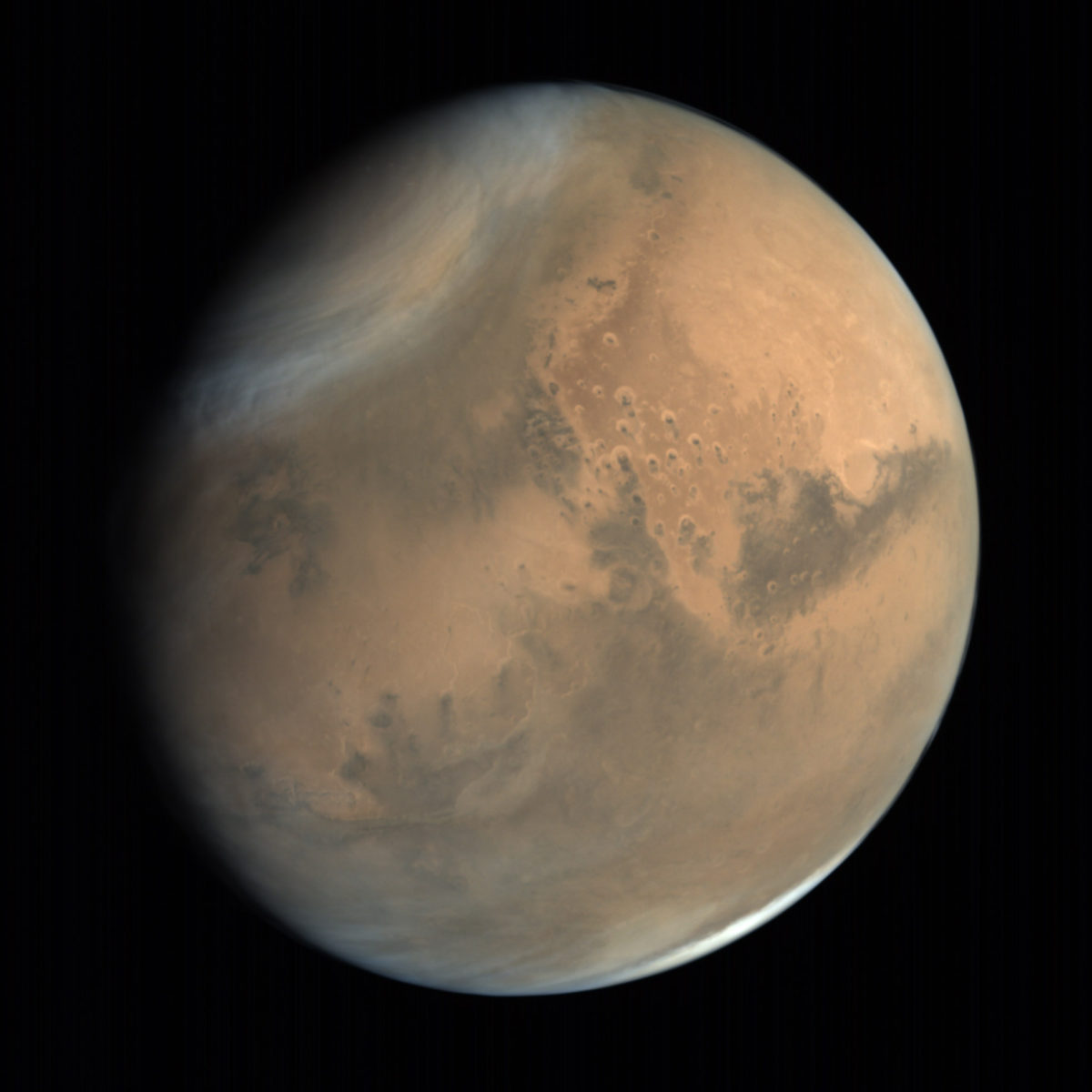

Now, China is looking to explore the wider solar system, starting with Mars—Huoxing, or literally 'fire star,' in Chinese.

The Plan

The path to a Martian sample return begins in 2020, when China plans to launch an all-in-one orbiter, lander and rover to Mars, using its Long March 5 rocket. The mission goals are vast, and include investigating soil characteristics, searching for water ice, assessing habitability, studying the atmosphere and tracking the weather.

The orbiter will carry a high-resolution camera comparable to that of HiRISE on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, capable of imaging the surface at 50 centimeters per pixel in relatively wide swaths. The lander will tentatively target one of two potential areas, the first being Chryse Planitia near the Viking 1 and Pathfinder landing sites, and the other including Isidis Basin and a section of Utopia Basin up to 30 degrees north.

The orbiter imagery would be used to examine potential landing sites for a future sample return mission. That mission, which would happen sometime in the late 2020s, hasn't been formally approved, but the Chinese space community appears increasingly serious about making it happen. High-ranking space officials and the country's main space contractor, CASC, are openly discussing the mission in public presentations. More significantly, the government's 2016 space white paper released late last year says China will "conduct further studies and key technological research" on bringing back samples from the Red Planet.

In June at an international space conference in Beijing, Chunlai Li, the deputy director of the National Astronomical Observatories (NAOC) under the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), stated the mission would study the structures, physical characteristics and components of Martian soil and minerals, investigate Mars' formation and evolutionary history, and assist with comparative planetology. Measurements taken from surface would be compared to readings from the samples returned to Earth.

Responding to a question during the session, Li confirmed that scientists are proposing astrobiology-related instruments for the two Chinese Mars missions, but decisions are still to be made.

There are many other factors yet to be decided, including intended sample size, collection methods, and measures to protect both the samples from Earthly contamination and our home planet from possible organisms brought back on the return journey.

The sample return mission would fly on a super heavy lift Long March 9 rocket (soon to enter development), allowing all phases—atmospheric entry, descent and landing, sampling, ascent, Mars orbit rendezvous and the journey home—to be completed with one launch from Earth. This contrasts with more complex, multiple-launch concepts being considered by NASA for its own sample return, including the collection and cache of samples by a different mission, the Mars 2020 rover.

Lunar proving ground

China's Mars missions will build on the country's experience with its past, present and future Chang'e missions to the Moon.

In 2007 and 2010, Chang'e 1 and 2 orbited the Moon. Three years later in late 2013, Chang'e 3 landed on the surface and deployed a small rover named Yutu (Jade Rabbit). Chang'e 4, which is scheduled to launch in late 2018, is a more ambitious version of Chang'e 3, with the added twist of sending the lander and rover to the lunar far side. This feat, which will require a telecommunications relay satellite to be launched to a spot beyond the Moon some six months earlier, would be the first by any nation.

This first set of lunar missions will culminate with Chang'e 5, a lunar sample return mission. Chang'e 5 was due to launch in late November this year, but has been delayed for at least a year due to the launch failure of the country's Long March 5 rocket in July.

Chang'e 5 is ambitious. Instead of a direct return to Earth like Soviet robotic sampling probes, the mission will rely on a lunar orbit rendezvous and docking to get 2 kilograms of Moon samples from an ascent vehicle to a reentry capsule.

This will be the first automated rendezvous around a planetary body other than the Earth and will be applicable for the future Mars mission—not to mention useful practice for future human landings on the Moon.

It's possible the returned Chang'e 5 lunar samples will be processed in facilities that could also host Mars samples. In accordance with the Outer Space Treaty, to which China, Russia, and the United States are all parties, a Mars sample return mission would require the most stringent precautions: Category V.

Is China ready for an interplanetary leap?

Sending probes to another planet is a huge scientific, technical, and policy challenge.

So far only NASA has performed a Mars entry, descent and landing on with complete success; attempts by the Soviet Union, Russia and European Space Agency have all failed. The success rate for Mars missions is just more than 50 percent. China's first attempt at a Mars mission, Yinghuo 1 ('Firefly 1'), involved piggybacking on the launch of Russia's Fobos-Grunt mission in 2011, but a rocket malfunction left that spacecraft stranded in Earth orbit.

Aside from making sure both Chang'e 5 and the initial Mars mission are a success, the Mars sample return mission relies on making Long March 9 rocket a reality. Given the development delays of Long March 5, and the challenges evident in the development of NASA's Space Launch System, getting a 100-meter-tall, 10-meter-diameter carrier rocket ready by the late 2020s cannot be taken for granted.

The traditional "space race" narrative born from U.S.-Soviet tensions in the 1960s doesn't always translate neatly to more modern space milestones. But as evidenced by apparent government, space sector and scientific support, China might be serious enough about a Mars sample return to surpass NASA's ambitions.

We might truly have ourselves a space race to Mars and back.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth