Jason Davis • Apr 19, 2017

This weekend, it's the beginning of the end for Cassini

It's the beginning of the end for Cassini.

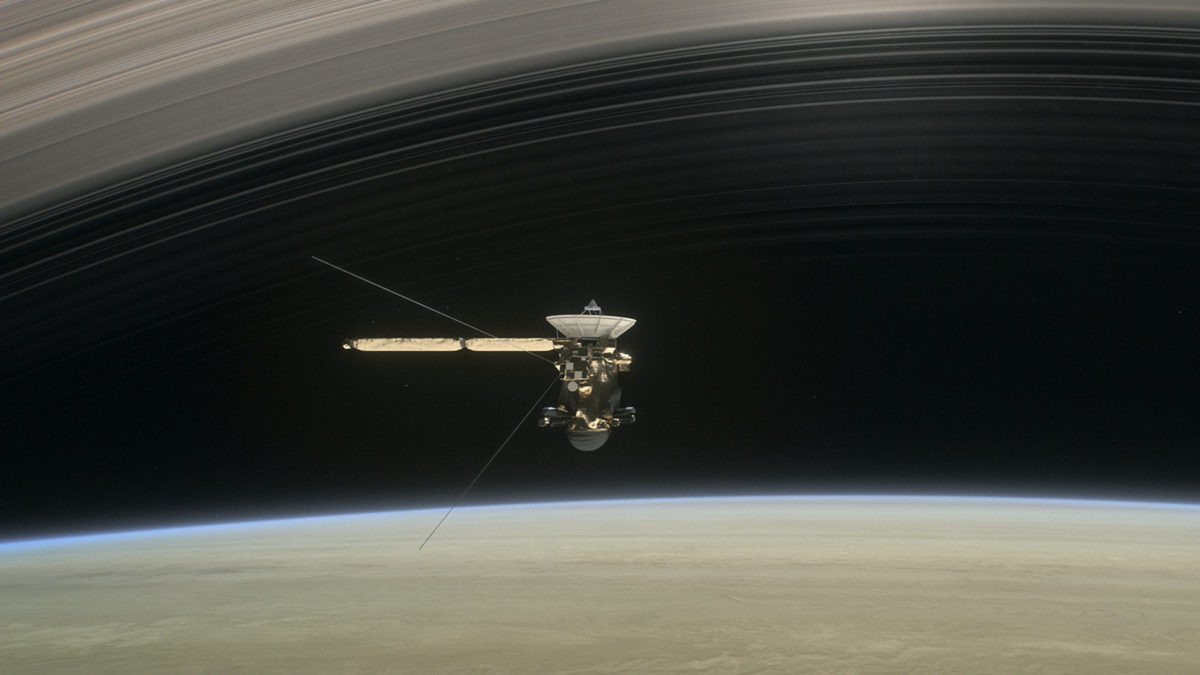

This Saturday, in the pre-dawn hours of Earth Day, NASA's long-lived Saturn spacecraft will buzz Titan for the 127th and final time. The moon's gravity will bend Cassini's trajectory, sending it into a new orbit that will slice between Saturn's rings and the planet itself—a feat never before attempted.

The flyby will also seal Cassini's fate. Twenty-two orbits later, the probe will tumble into Saturn's atmosphere on September 15.

Why end the mission? After 13 years of operations, Cassini is low on fuel, and NASA doesn't want to risk an accidental collision with the potentially habitable worlds of Enceladus and Titan.

"Cassini's own discoveries were its demise," said project manager Earl Maize during a recent press conference. "Enceladus has a warm, saltwater ocean. We cannot risk inadvertent contact with that pristine body."

The Grand Finale

Cassini's closest approach to Titan technically occurs Saturday, April 22 at 2:08 a.m. EDT (6:08 UTC). At that time, the probe's altitude will be about 1,000 kilometers—a little more than double the height of the International Space Station.

Cassini will spend its final close flyby scanning Titan's methane lakes, focusing in particular on the "magic island" feature that has changed shape over the course of multiple observations. The spacecraft will also make some new lake depth measurements.

The first ring crossing will occur three days later, on April 26. NASA is dubbing this phase of the mission the Grand Finale—with good reason.

"I wouldn't be a bit surprised if some of the discoveries we make with Cassini might be the very best of the mission," said Linda Spilker, the mission's project scientist.

The ring crossings will provide wild, closeup imagery of Saturn's clouds and rings from never-before-seen angles. Cassini may be able to see ring pieces as small as a kilometer across. Instruments on board the spacecraft will reveal new insights about the planetary system, including the mass of the rings.

An accurate mass reading could help scientists solve a long-standing puzzle: How old are the rings, and where did they come from?

"If the rings are a lot more massive than we expect, perhaps the rings are old—maybe as old as Saturn itself," Spilker said. "On the other hand," she said, "If the rings are less massive, perhaps they're very young—maybe forming as little as a hundred million years ago. Maybe a moon or a comet got too close, and got torn apart by Saturn's gravity."

Risky business

The ring dives are risky. Scientists can't say with absolute certainty where Saturn’s innermost ring ends, so Cassini will hug the planet, sailing above its cloud tops at a height of just 3,000 kilometers.

Joan Stupik, a Cassini guidance and control engineer, said the spacecraft will be traveling at a blistering 34 kilometers per second. For protection, it will turn its large, high-gain antenna dish toward its direction of motion.

"We want to protect all of the science instruments on the body of the spacecraft," Stupik said. "At those speeds, even a tiny piece (of dust) could do damage to our spacecraft."

Cassini grand finale promotional Video: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Emotional ending

On Wednesday, Cassini will skim the outer edge of Saturn's rings for the final time, en route to its fateful encounter with Titan.

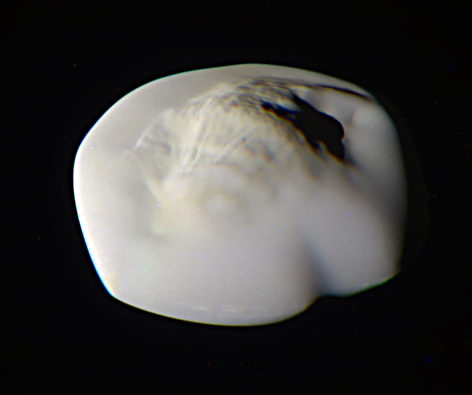

During the spacecraft's penultimate ring pass April 12, it snapped new images of Atlas, a 30-kilometer-wide moon that sits outside Saturn's bright outer ring, the A ring.

In five months, pictures like this will be no more. Cassini will transmit its final images before beginning its very last plunge September 15. Then, it will turn its attention to Saturn's atmosphere, sniffing with a mass spectrometer and sending data back to Earth in real-time.

Eventually, Cassini will be torn apart. At the moment NASA's Deep Space Network loses contact, the spacecraft will already have been gone for about an hour and a half—the time it takes for the spacecraft's signal to travel to Earth.

It will be an emotional end—especially for scientists that have worked on the mission.

"I've worked on the Cassini mission for almost three decades," Spilker said. "My oldest daughter, Jennifer, started kindergarten when I started working on Cassini, and now she's married and has a daughter of her own."

"Cassini received federal funding in 1989, and I was born in 1989," said Joan Stupik. "So you could say we're the same age."

Are you a Planetary Society member? The September Equinox edition of our flagship magazine, The Planetary Report, will be jam-packed with articles and imagery celebrating the Cassini mission. We've covered Cassini since the beginning, and we'll be there at the end. Don't miss this special issue!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth