Jason Davis • Mar 23, 2017

A repeat of the space shuttle's bold test flight? NASA considers crew aboard first SLS mission

Last month, NASA announced it was considering flying astronauts on the first flight of the Space Launch System.

It was an eyebrow-raising proclamation. Since the unveiling of the mega-rocket's design in 2011, the agency has always planned on having the first flight blast an uncrewed Orion spacecraft to the Moon. Originally, this was supposed to happen at the end of 2017, but it has since slipped to late 2018.

Adding crew to the mission could be risky. SLS is a brand-new rocket, and Orion has only flown once—in a barebones configuration atop a different rocket.

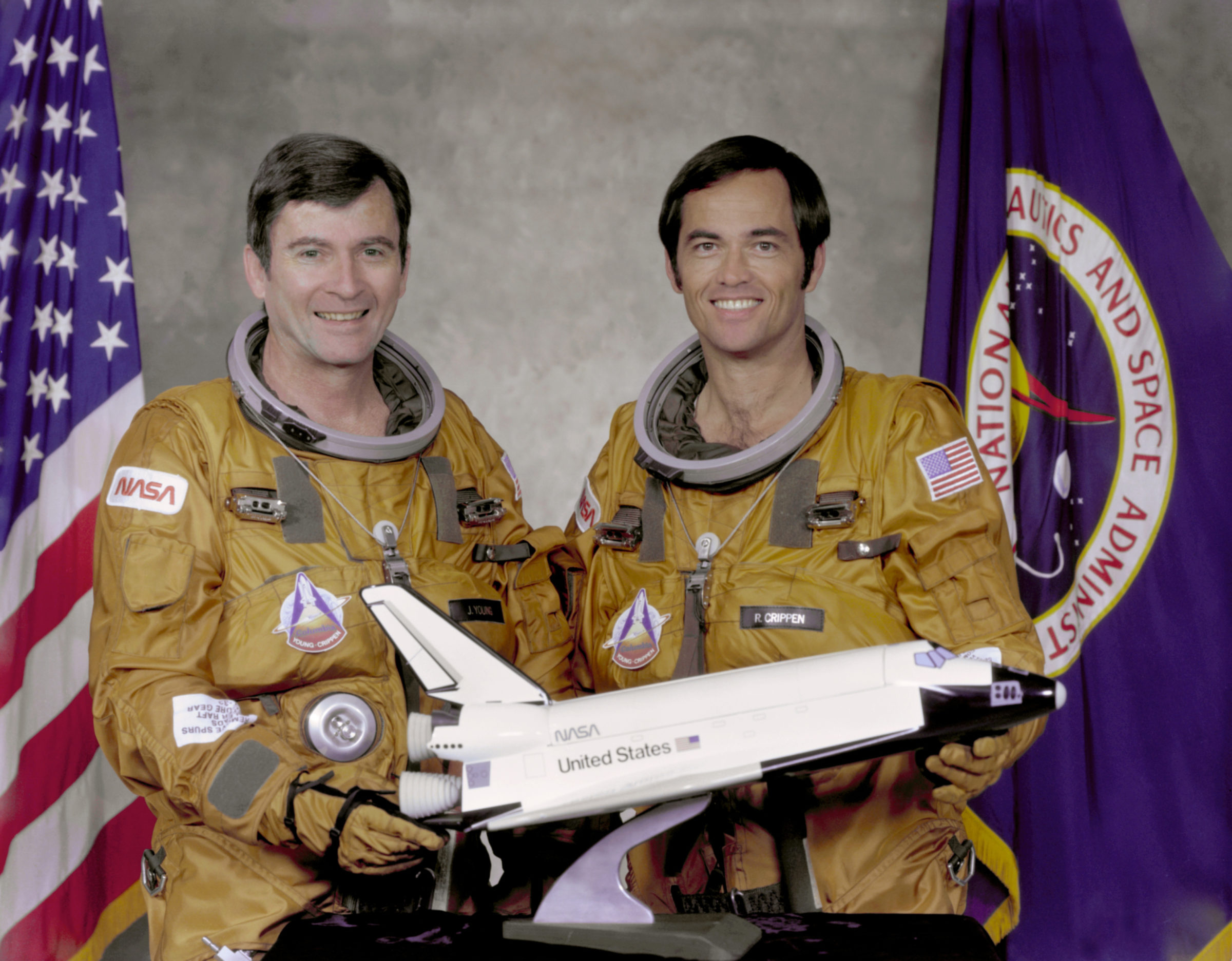

NASA has only flown astronauts on a launch vehicle's maiden mission once, when John Young and Bob Crippen took space shuttle Columbia on the boldest test flight in history.

Could we see a repeat of Columbia's daring mission? How risky would that be, and why consider changing the plan at all?

The motivation

NASA has been quick to note that it is only assessing the feasibility of adding astronauts to the first SLS flight—until then, it is remaining neutral on the idea.

During a press call with reporters on Feb. 24, agency officials said the assessment was requested by the Trump administration.

"We've had early discussions with the transition team, both before the inauguration and after, about accelerating our crew capability," said Bill Hill, the deputy associate administrator for NASA's exploration systems division. Hill's boss, associate administrator William Gerstenmaier, said the request came from "Robert (Lightfoot) and the new administration." Lightfoot is NASA's acting administrator. He's a civil servant, not a political appointee—though he still reports to the White House.

Why, exactly, the Trump administration or its transition team requested the study is unclear, but most sources I spoke with for this article cited two plausible reasons.

Both are political.

Firstly, as it stands, no NASA astronauts will fly beyond low-Earth orbit during President Trump's first term, since the second SLS flight, which will carry crew, is not scheduled to occur until at least 2021. There is a chance SpaceX could send two tourists around the Moon during Trump's first term; right now, that's scheduled for 2018, but the date will likely slip.

NASA said it will only considering adding a crew to the first SLS flight if the mission would be ready to fly in 2019—otherwise, they'll stick with the current plan. But if there indeed is a way to make the flight happen in 2019, it could provide a high-visibility achievement for President Trump.

A second theory centers on pressure to get SLS and Orion flying astronauts as quickly as possible.

Despite various media reports predicting the Trump administration might ditch SLS and Orion in favor of vehicles from other firms like SpaceX, the Trump administration's 2018 budget blueprint gave no indication of an impending large-scale shift for NASA. In fact, the opposite happened: SLS, Orion and the vehicles' associated ground systems received a 23 percent funding increase over President Obama's 2017 budget request.

Additionally, Trump recently signed a new NASA authorization bill, backed with overwhelming House and Senate support, that advocates avoiding major program changes.

Nevertheless, one industry analyst I spoke with predicted that until SLS and Orion are fully operational, they remain vulnerable. Getting the vehicles flying crews quickly could cement their futures and ward off any remaining threats from other would-be commercial providers.

No matter the motivation, Matthew Hersch, an assistant professor and historian of technology at Harvard University, doesn't think it's worth the risk.

"The only reason to hurry up and put people on there is to try and score a short-term political victory," he told me. "That's the kind of political pressure that gets people killed."

Hersch, the author of "Inventing the American Astronaut," as well as an upcoming book on the origins of the space shuttle program, said he was concerned NASA's fortunes were being tied to "a series of elaborate stunts."

"It actually sounds very Soviet, much the way competing design bureaus in the Soviet Union used to act in an effort to attract attention for their respective science programs," he said.

The precedent

On April 12, 1981, astronauts John Young and Bob Crippen climbed aboard space shuttle Columbia and blasted off on a 2-day shakedown cruise. Beyond a series of glide tests, the shuttle had never flown.

I contacted Crippen to ask about the mission, and get his perspective on the risks involved in flying astronauts on a new vehicle. He declined to be interviewed, saying he preferred to let NASA conduct its feasibility study first. He did, however, tell me he thought flying SLS and Orion without a crew first seemed like "a good idea."

Prior to Columbia, NASA flew its rockets without people first for a very simple reason: they used to blow up a lot more.

The first two Mercury flights of Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom in 1961 were brief suborbital jaunts atop the Army's Redstone booster. For John Glenn's orbital flight, NASA switched to the more powerful Atlas rocket. The very first time Glenn showed up to watch an Atlas test flight, the mission ended in disaster shortly after liftoff.

"That wasn't a confidence builder," Glenn later said.

By the time the shuttle flew, NASA had a better track record, and computer simulations were able to more accurately predict a vehicle's performance, giving engineers a higher certainty things would go right on launch day.

Mike Neufeld, a senior curator in the space history department at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, said it was decided relatively early in the shuttle's development cycle that a pilot would have to be in the cockpit to fly the shuttle during landing. And there was no shortage of astronauts ready to give it a try.

"NASA picked test pilots for Mercury, and soon after they arrived, they said, 'Hey, we're not going to just be passengers on these things,'" he told me. "So that's really embedded in the history of the U.S. human spaceflight program."

This was a stark contrast, he said, with the Soviet Union's space program.

"The first class of cosmonauts were these 25-year-old kids who just ordinary jet pilots taken from the Soviet Air Force," said Neufeld. Soviet spacecraft were highly automated, and this mentality extended all the way to Buran, the legendary Soviet shuttle clone that only made a single test flight—an automated one.

NASA astronauts continue to play a large role in the development and operations of their spacecraft. But since the shuttle days, the agency has returned to its automated roots. Orion can fly without a crew; as can upcoming commercial vehicles like Boeing's Starliner and SpaceX's Crew Dragon.

Heritage technologies

If NASA does put a crew on the first SLS mission, it would probably be a lot safer than Columbia's flight.

Most SLS components are shuttle-derived. The core stage is essentially a shuttle external fuel tank with four shuttle main engines mounted at the bottom. All four of the engines slated for the first SLS flight have already carried shuttles into space. The SLS side-mounted solid rocket boosters are effectively shuttle boosters with extra propellant segments.

Orion has already flown once. In December 2014, a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket blasted an Orion capsule to an altitude of 5,800 kilometers, subjecting it to a high-velocity atmospheric reentry meant to simulate a lunar return. Orion's European-built service module is based on the Automated Transfer Vehicle, which is used by the European Space Agency to ferry cargo to the International Space Station.

The biggest question mark may be the rocket's upper stage.

The first SLS flight will use a Delta IV upper stage—the same used for the 2014 Orion test flight—called the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, or, ICPS.

The second SLS flight—meant to be the first crewed flight, no earlier than 2021—will use the under-construction Exploration Upper Stage, or EUS.

Both stages use Aerojet Rocketdyne RL-10 engines. But the ICPS only has one engine; the EUS will have four.

This presents NASA with a bit of a paradox: the ICPS has flown; the EUS has not. But the ICPS was never meant to carry humans, whereas the EUS is being built with humans in mind from the start. Deciding which coniguration is safer, then, is hard to judge. (In 2015, NASA said the ICPS could be human-rated at a cost of $150 million.)

If anything goes wrong during the initial climb to orbit, Orion is equipped with a traditional escape tower that would pull the capsule away from SLS. The space shuttle, on the other hand, relied on a risky return-to-launch-site abort scenario that involved ditching the solid rocket boosters and external fuel tank, turning the shuttle around, and gliding back to Kennedy Space Center.

"There's a very limited set of circumstances in which that would have worked," Neufeld said. "And obviously, the orbiter had to stay intact."

NASA actually considered testing this abort mode on Columbia's first flight, before ultimately deciding flying all the way to orbit was safer.

Human spaceflight: still dangerous

If NASA and the Trump administration do indeed decide to put a crew on the first SLS flight, they probably won't have a hard time finding astronauts to volunteer for the mission.

When Columbia returned to Earth on April 14, 1981, the New York Times ran a front-page photo of the shuttle approaching the runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California. One story subhead declared "FLIERS EMERGE ELATED."

Alex McCool, a retired NASA propulsion expert who worked on everything from Redstone rockets to shuttle engines, was there in the desert that day. McCool, now an emeritus docent at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, recently described to me what he remembered about the landing.

"Here's John Young. He gets out of the orbiter, walks all around it, looking underneath, jumping up and down—he was excited," McCool said. "Of course, we were too. Seeing that thing, hearing the sonic booms—after they landed, we were all on a high."

But despite Young and Crippen's bravado, NASA still lost two orbiters and 14 crewmembers during the 30-year space shuttle program.

The problems that ultimately doomed Challenger and Columbia were present from the start. Engineers at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center were worried about solid rocket booster joints as early as 1977. And damage to the shuttle's thermal protection system occurred on multiple flights—most severely during STS-27 in 1988.

It's a grim reality of spaceflight: test flights, whether crewed or uncrewed, do not eliminate the possibility that humans might be killed.

"On balance," Neufeld said, "All we can really say is that traveling into space is dangerous, and will remain so for some time."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth