Jason Davis • Jan 03, 2017

A company you've never heard of plans to build the world's first private space station

Not many people have heard of Axiom Space outside a small segment of the space community.

The company didn't exist until 2016, and only has a half-dozen employees. Yet it only takes a quick glance at the company's publicity materials or a chat with one of its representatives to see that the name Axiom fits well.

An axiom is a statement that is established, accepted or self-evidently true, and that's how the company talks about its future. They aren't planning to build the first private space station—they're doing it. They aren't hoping to launch a mutlipurpose module to the International Space Station in 2020—they are. An Axiom-sponsored astronaut isn't projected to visit the station in 2019—he or she is.

It's all so straightforward and matter-of-fact, you find yourself asking: Does Axiom know something I don't?

Quite possibly. The company, led by Mike Suffredini, who managed NASA's ISS program for 10 years, and Kam Ghaffarian, the CEO of SGT, a major NASA contractor responsible for ISS operations and astronaut training, has big ambitions that could potentially re-shape the space industry. Will they be able to pull it off?

The plan

Axiom plans to build the core of its space station at the ISS before the international laboratory retires, which is currently scheduled for 2024 but could be delayed until 2028. When the ISS finally calls it quits, Axiom's station will detach and become a fully independent commercial complex.

The company's first module, called the "Multi-Purpose Module," or simply, Module 1, would launch in late 2020. The current plan is to heave it into space all in one shot, providing Axiom can find the right rocket; at about 9 meters long and 5 meters wide, Module 1 will be a huge payload. (An alternative concept is launching the module in pieces and assembling it in space.)

Module 1 has its own propulsion system, meaning it will fly to the ISS under its own power after being dropped off in orbit. Axiom is currently proposing NASA connect the module to the forward-most port of the ISS, where a new mating adapter was recently installed to accommodate commercial crew vehicles. That mating adapter could then be moved to Module 1 and still be used for U.S. crew vehicle access.

Axiom and NASA have conducted a feasibility study on the concept, and are currently discussing all this under a Space Act Agreement; formal commitments have yet to be made. Officials at the agency's Johnson Space Center did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The extent to which Axiom's customer astronauts would interact with the rest of the ISS is still unclear, but Module 1 will be self-sustained from the get-go. It has its own life support systems, sleeping quarters, restroom, galley, and experimentation and storage areas. Axiom says the module can support up to seven astronauts—though there probably won't be a lot of elbow room until the company adds up to two more modules between 2020 and 2024.

I recently spoke with Amir Blachman, the company's vice president of strategic development, and asked him who would build Module 1.

"Structurally, we're going to be utilizing one of the companies that built most of ISS," he said, adding the module would have a rigid structure and be similar in appearance to existing ISS components. Axiom expects to formally announce which company will build Module 1 around May or June of this year.

Initially, the company won't employ its own astronauts. The space station will serve as an off-world co-working habitat, with Axiom training crewmembers that want to use its facilities. The training will be conducted by SGT, the aforementioned contractor that currently trains NASA astronauts.

In 2019, Axiom plans to send a customer's astronaut to the ISS for a short-duration stay before the first module arrives. Because of the time required to prepare for the mission, the astronaut will begin training this year—meaning Axiom is set to begin generating revenue. The company hasn't formally booked a ride to orbit, but but Blachman said it would likely be on either a Soyuz or Dragon flight.

Commercial market

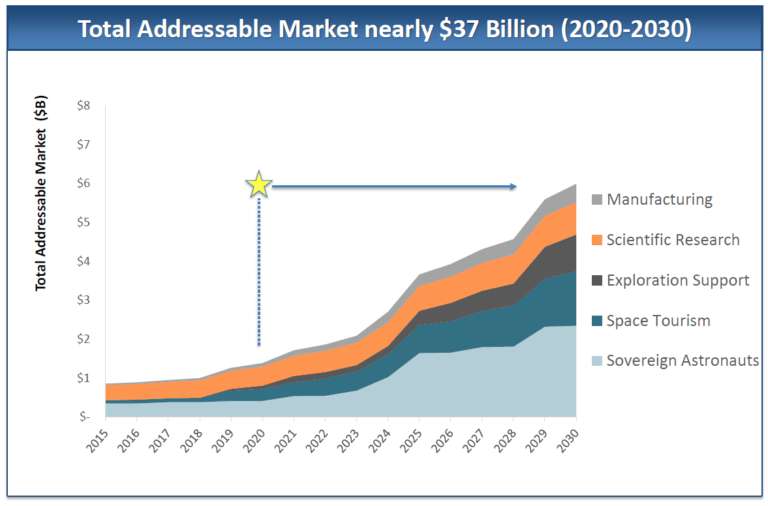

According to Axiom, a private space station can address a market of up to $37 billion between 2020 and 2030.

The actual figure will be lower if the ISS remains operational beyond 2024, but Axiom still expects a substantial revenue stream as soon as Module 1 is in place. I told Blachman I was skeptical: If such a huge market exists, why hasn't anyone already stepped in to fulfill it?

He said the company's top funding source would be sovereign countries wanting to send their own astronauts into space.

"There are more than 20 countries that want to send astronauts into space," he said. Some of those already have human spaceflight programs, while others want to develop one for reasons that include national prestige and fostering STEM education and technology development.

There is a currently a backlog of these would-be astronauts, Blachman said, due to limited ISS capacity and a shortage of launch vehicles.

The ISS can only support about seven crew members at a time. There are always two NASA astronauts, and even after Russia's decision to reduce its crew complement to two, either ESA or JAXA has an astronaut on board at least half of the time.

The other limiting factor is Soyuz seats. The stalwart Russian spacecraft can only hold three people, which keeps the station's staff count at six, until SpaceX and Boeing begin flying crew vehicles in 2018.

But even then, NASA wants an extra astronaut of their own aboard in order to conduct agency-sponsored research. Axiom's station, then, offers a commercial alternative for sovereign astronauts.

Other revenue sources

Another funding stream is space tourism. Axiom-sponsored tourists won't look like those planning to book a suborbital flight with a company like Virgin Galactic.

Most notably, Axiom will require its space tourists to undergo much more extensive training, and the ticket price will be quite different. Whereas Virgin Galactic is currently charging $250,000 for a few minutes of weightlessness, Axiom will offer seven-to-ten day missions.

"It'll probably be significantly less expensive than what it costs for tourists to go to space now, but it's still going to be in the tens of millions," Blachman said.

The rest of Axiom's potential market comes from exploration support, scientific research, manufacturing, and sponsorships. Blachman attributes the potential growth in some of these areas to "zeitgeist and timing"—spurred in part by CASIS, the non-profit group that helps private companies and organizations conduct research and technology demonstrations aboard the ISS.

It is unclear how much money private organizations have invested in CASIS or NASA-sponsored ISS experiments thus far. CASIS did not respond to interview requests, but according to their website, the group has backed 144 projects since 2012. During that five-year period, CASIS awarded about $27 million in grants.

Axiom seems to believe the market for commercial space research and manufacturing is approaching a tipping point that could slide in the company's favor.

"If you go to a materials science, bio science, pharma or metallurgy conference, there probably aren't a lot of people today talking about "What can I do with zero gravity? What alloy can I make? What crystal can I grow?" We're really only starting to see that pick up now," Blachman said.

The company also believes there is an increasing number of early career entrepreneurs that would like to get into the on-orbit business. Furthermore, as NASA's deep space exploration efforts shift from low-Earth orbit to lunar space, Axiom's station will offer a close-to-home destination for commercial companies looking to test new technologies.

"They're going to want somewhere near Earth where they can test life-critical and mission-critical systems," said Blachman. "Where are you going to do that?"

The competition

Of the dozens of NewSpace firms proposing projects on the scale of Axiom's space station, few have succeeded.

But Axiom has a chance. Mike Suffredini and Kam Ghaffarian have a lot of ISS experience. Also on the team is Stephen Altemus, a former Johnson Space Center engineering director, as well as two astronauts, and Blachman, a seasoned venture capitalist.

Blachman said that in addition to having secured early funding, Axiom is poised to close its first major round of stock financing, known as Series A. He expects 2017 to be a big year in terms of finalizing the company's plans.

Also in Axiom's favor is a lack of competition. Though China plans to build its on space station starting in 2018, and Russia has expressed its own desire to attach new modules to the ISS, it is doubtful either country could support the commercial market Axiom envisions.

That leaves Bigelow Aerospace, which attached its inflatable BEAM testbed to the ISS in 2016. After BEAM detaches in 2018, Bigelow has proposed testing its much larger B330 module on the station. Whether it would have to compete for the same forward port is unclear, though artist's concepts released as part of NASA's NextSTEP program do show the B330 attached to the same spot. Axiom deferred questions on this subject to Bigelow and NASA; Bigelow representatives were not available for comment.

In any case, it's full speed ahead for Axiom, and Blachman believes the company is poised to help the space community transition into a post-ISS world.

"Based on our relationships with industry and customers, and our unique mission and training expertise, our team is ready to accomplish this ambitious undertaking," he said.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth