Jason Davis • Feb 10, 2016

SLS CubeSats to Set Sail for Deep Space

In 2018, NASA's Space Launch System will blast off on its maiden voyage, sending an Orion spacecraft on a three-week trip to lunar orbit. After Orion is released in translunar space, a ring of small, secondary spacecraft will be deployed from the rocket's stage adapter. These 13 lucky CubeSats will be beneficiaries of a free, moon-bound boost—something most hitchhiking hardware never gets to experience.

One of the CubeSats, NEA Scout, will use a propulsion technology familiar to Planetary Society members: solar sailing. Solar sails harness the gentle push of solar photons for a small but continuous acceleration that, over time, can propel spacecraft to speeds higher than their chemical-powered counterparts. A second CubeSat called Lunar Flashlight had also planned to use a solar sail, but ultimately swapped the sail for a conventional propulsion system.

NEA Scout will loiter in lunar orbit before embarking on a two-and-a-half year mission to a near-Earth asteroid. The current target—should NASA's SLS launch schedules hold—is named 1991VG. The tiny, 7-meter-wide world has an orbit barely bigger than Earth's, making a trip around the sun every 380 days. Conspiracy theorists will be pleased to know there have been debates over whether the object is natural or artificial.

"This is a reconnaissance mission," said Les Johnson, NEA Scout's solar sail principal investigator, in a phone interview with The Planetary Society. "We're answering some strategic knowledge gaps for human exploration. What does the surface look like? Is there a debris cloud around it? Is it a rubble pile? Is it one big rock?"

By the time NEA Scout reaches its asteroid, it will have picked up too much speed to slow down for a close look. The solar sail will whizz past its target at a speed between 10 and 20 meters per second. That's still relatively slow, compared to a probe like New Horizons, which passed Pluto at a staggering 11 kilometers per second. As such, NEA Scout should be able to image about 85 percent of the asteroid's surface.

At 86 square meters, NEA Scout's solar sails are more than double the size of those used by The Planetary Society's LightSail CubeSat. The core spacecraft is also twice as big; NEA Scout is a six-unit CubeSat the size of a large shoebox. But there are still similarities between the two missions, with both tracing their heritage back to NASA's original Nanosail-D CubeSat design. Johnson's team has been collaborating with LightSail engineers to share lessons and compare notes. "It's been very beneficial, the exchange of information," he said.

After NEA Scout is ejected from the SLS stage adapter, it will use its single thruster to stabilize itself and enter orbit around the moon. Then it will deploy its solar sails and use subsequent flybys to set up a departure for its target asteroid. The spacecraft won't be able to reach its destination without the thrust obtained from solar sailing, so rigorous ground testing is absolutely essential.

For some tests, the NEA Scout team uses a half-size prototype sail on a special "flat floor" at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The flat floor uses compressed air to help objects glide across the surface, creating a low-friction environment for deployment testing.

But in a pinch, there's another low-friction surface that will work, Johnson said. "We wanted to test out other options, so we took it over to the basketball court. We found that it actually worked pretty well."

There are NEA Scout team members at both Marshall and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. That's the same arrangement for Lunar Flashlight, another CubeSat hitching a ride to the moon in 2018.

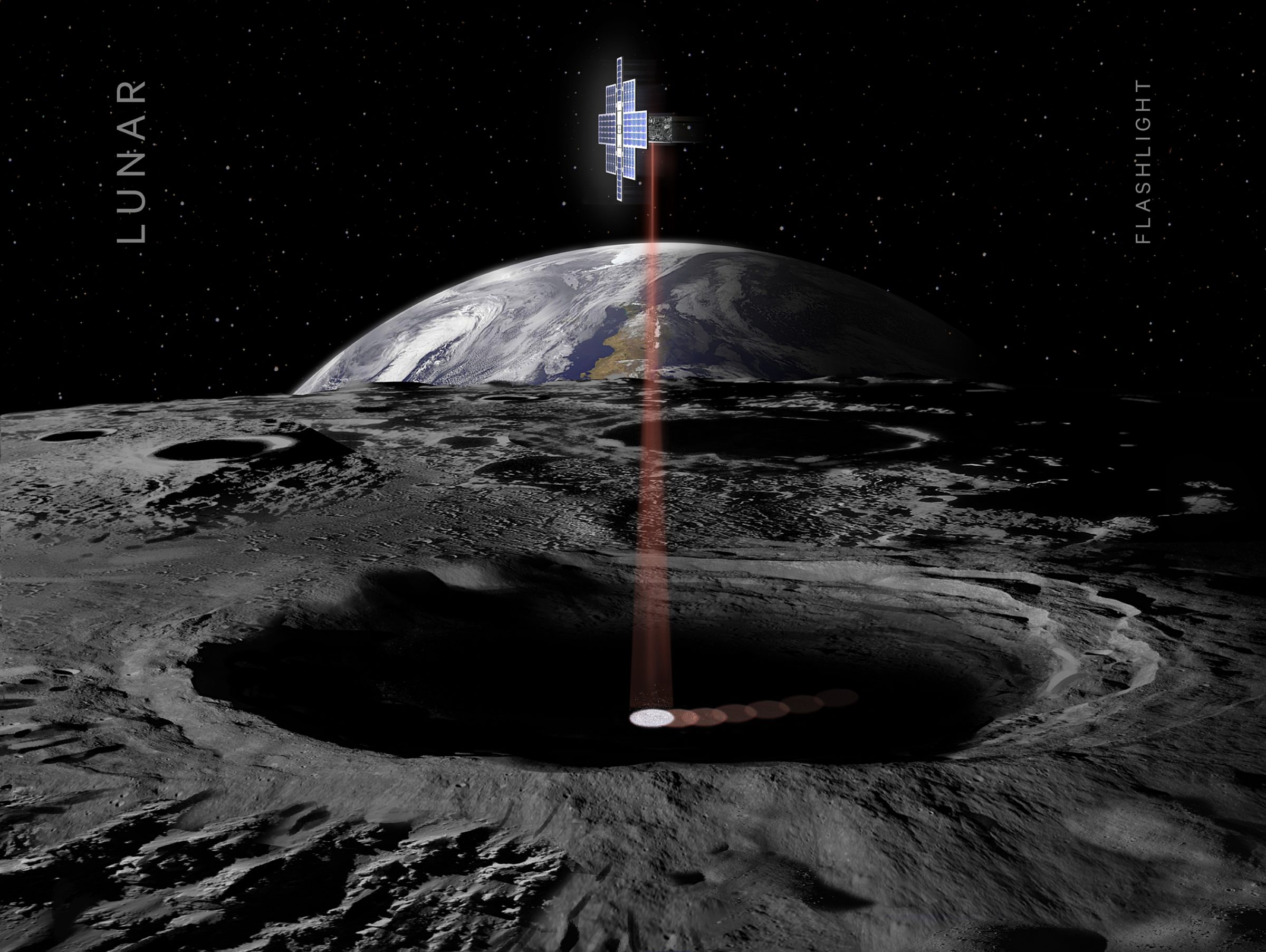

Lunar Flashlight will look for ice deposits in the moon's permanently shadowed craters at the south pole. It will fly in a highly elliptical orbit, dipping as close as 20 kilometers from the surface at closest approach. The spacecraft looks for lunar volatiles by shining near-infrared lasers into darkened craters and measuring the composition of the reflected light.

"One of the great things about laser is that it's a very tightly constrained wavelength," said Barbara Cohen, the science lead for Lunar Flashlight, speaking by phone about the project. "So we don't expect that wavelength to change very much on its return—it bounces off and returns in the same wavelength." By tuning two of the four lasers to water absorption band wavelengths, Cohen's team should able to infer the presence of water.

Making a better map of lunar ice deposits will come in handy for future missions that hope to use the ice as a resource, including possible human expeditions. In the early 2020s, NASA hopes to launch a rover called Resource Prospector to test out in-situ resource utilization techniques.

Therefore, it would be helpful if Resource Prospector knew exactly where to go, Cohen said. "We really need a better map of where that water ice exists, so that when you send a surface asset like a rover to someplace that's 25 kelvin, you can be sure that you're going to the right place."

Back when Lunar Flashlight still had a solar sail, the spacecraft team was considering using the sail as a reflector to shine sunlight into its target craters. Like NEA Scout, the sail size would have been 86 square meters. Initial tests of both spacecraft showed the large sail had a tendency to yank the spacecraft around, making attitude control difficult. To solve the problem, the designers of NEA Scout implemented a system akin to a ballast mass that dynamically changes the CubeSat's center of gravity.

But for Lunar Flashlight, this trick turned out not to be feasible. The spacecraft has stricter mass requirements for getting into lunar orbit, and the sunlight-reflecting sail plan required precision pointing.

"So we ran up against a physics limitation," Cohen said. "The ways that we use solar sails across the solar system are going to be great for some things, and maybe not great for other things."

Lunar Flashlight, NEA Scout and the rest of the moon-bound CubeSat fleet is currently scheduled to launch aboard the Space Launch System in 2018.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth