Jason Davis • Dec 01, 2015

Orion Service Module Faces Roller Coaster of a Ride in Sandusky

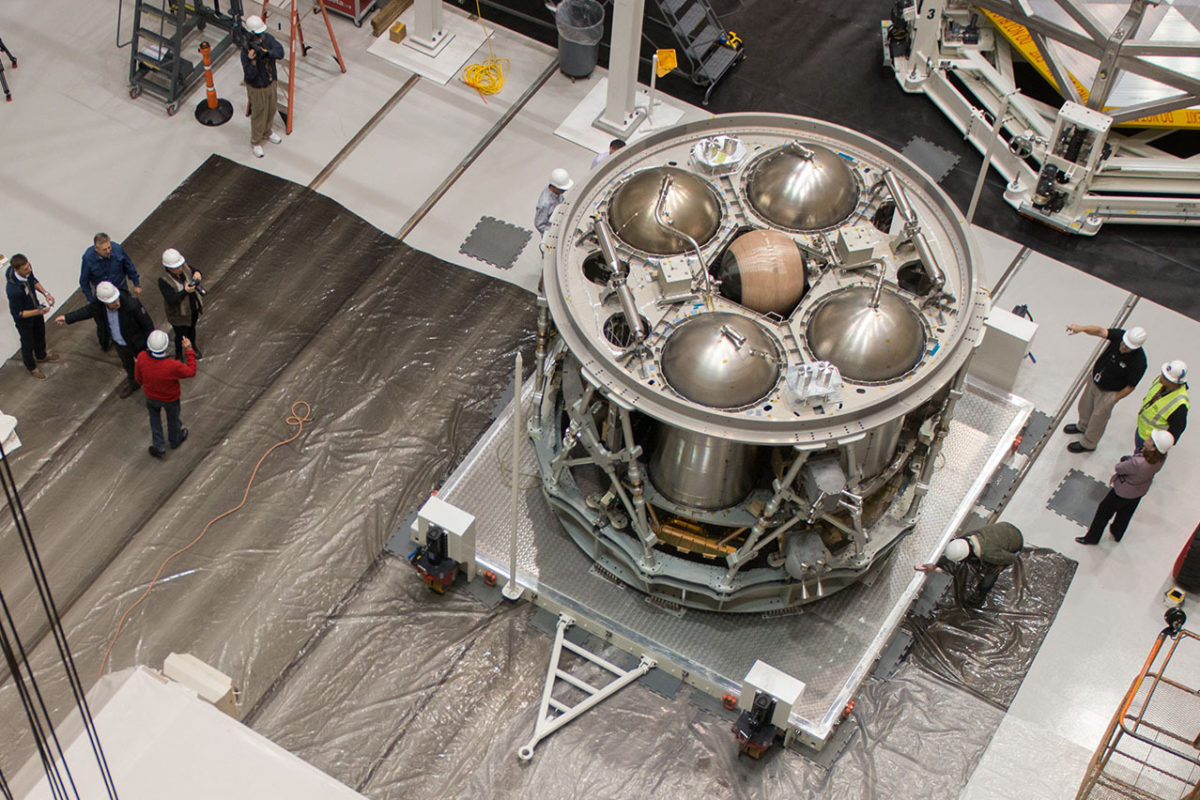

On the Monday after the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday, representatives from NASA, the European Space Agency and two of the world's largest aerospace giants sat down for a press event in front of a test version of the Orion service module. The module—referred to by NASA as the European Service Module (ESM) test article—recently shipped across the Atlantic to NASA Glenn Research Center's Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio. There, engineers are preparing the ESM for a barrage of stress tests to make sure the real thing is ready to fly with Orion to the moon for a shakedown cruise in 2018.

Sandusky is perhaps better known for the Cedar Point amusement park, the self-proclaimed roller coaster capital of the world. About 40 minutes into Monday's press conference, an NBC reporter from Toledo pointed out that "a lot of folks in our area don't know that this facility exists. They know that Sandusky is the home of Cedar Point, where they go to ride roller coasters, but they don't know that the big roller coasters are being built here—or at least, tested here."

Jim Free, the director of the Glenn Research Center, said, "I actually think Cedar Point is second to us." Among the many space-bound things Plum Brook has tested are the heat-dissipating radiators aboard the International Space Station, and a multitude of rocket payload fairings—including the ones that will shroud NASA's multi-billion-dollar James Webb Space Telescope when it launches in 2018.

"This place is part of the legacy of what's flown in space," Free said. "This place is part of the space program in years past, and with what you see here today"—referencing the ESM test article behind him—"will be part of the space program for years to come."

The ESM measures 4.1 meters wide and 4 meters tall. It attaches to the bottom of the gumdrop-shaped Orion command module, which houses the crew. The bottom of the ESM has a large engine for getting Orion into and out of lunar orbit. The module also has 7.5-meter-long solar arrays for power, air and water for the astronauts, and radiators for keeping the craft cool.

Without the service module, Orion can't fly. Without Orion, the service module is just a cargo hauler—and that's exactly what it used to do. The ESM design is based on the Automated Transfer Vehicle, which the European Space Agency, ESA, used for ferrying cargo to the International Space Station. The Europeans signed up to provide the first Orion service module three years ago, in December 2012. As part of the agreement, ESA gets to count the ESM against some of their required ISS financial contribution.

The service module also positions ESA as a key partner in NASA's future human exploration programs.

"Obviously, the ultimate objective is to have an ESA astronaut flying beyond low-Earth orbit," said Nico Dettmann, a development department head for the agency, who also once ran the Automated Transfer Vehicle program. "We hope that this cooperation will actually lead to having a European astronaut on such a mission."

Greg Williams, the deputy associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations at NASA Headquarters, took that idea beyond low-Earth orbit—all the way to Mars. "We would love to see astronauts from several nations be involved when we first set foot on the Red Planet," he said.

International cooperation, the panel agreed, has been an ESM success story, building on what has already been achieved with the dozen-plus member-nations of the ISS program.

But integrating a spacecraft built on separate continents hasn't been easy, said Mike Hawes, the program manager for Orion at Lockheed Martin, which is building the command module. "It's a little challenging," Hawes said. "You can't go down the hallway to talk." To make communications flow more easily, Airbus Defence and Space, the ESM contractor, has deployed teams in the U.S., while Lockheed and NASA regularly send representatives to Bremen, Germany, where the flight version of the ESM is being built.

The Orion command and service modules work together intricately. For example: The service module solar panels feed batteries in the command module, while the command module tells the solar panels which direction to point. "These are not modules that you can just bolt together and say you're good to go to fly," Hawes said.

Oliver Juckenhoefel, the vice president and head of Airbus's ESM program, agreed. "I'm not sure what is most costly in this program, the telephone bill for our teams, or any of the hardware you see there," he said.

Starting in February 2016, more of those Airbus phone calls will be routed through Sandusky, when Orion's roller coaster test ride begins in earnest. The tests will focus on making sure the module can survive a trip to orbit aboard the Space Launch System, NASA's new heavy lift rocket.

"When we launch on the world's most powerful rocket, we are going to be shaken and vibrated," said Mark Kirasich, Orion's NASA program manager. "We have to make sure we can survive that."

The agency says there's no better place to do that than Plum Brook Station, home of the world's most powerful acoustic spacecraft test chamber. The ESM will be blasted with 152 decibels of sound, equivalent to 20 jet engines at full power. It will then move to a huge vibration table that will shake it from "every possible angle." The module's solar arrays will be deployed, and the explosive charges used to release the spacecraft's payload fairing—as well as separate the service module from capsule—will be test-fired.

Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur, representing Ohio's ninth congressional district, said the level of Orion testing will be an order of magnitude more sophisticated than anything previously attempted at Plum Brook Station. NASA said it took several years to build out the facility to support Orion testing. As for cost, Kaptur said it took "millions and billions, literally, to construct."

"There's no other place like this on Earth," she said.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth