Jason Davis • Oct 29, 2015

At Mars Workshop, Science and Human Spaceflight Find Common Ground

Richard Davis was once unsure how scientists would react to the idea of using Mars satellites to scout for potential human landing sites.

The assistant director for science and exploration at NASA’s Science Mission Directorate was at a Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group meeting, and recalls expecting the idea to go over "like a lead balloon." But to his surprise, it didn’t. The scientists were engaged, eager to help and wanted to work together.

"I was so wrong," he said. "I think there's a growing recognition that to make the next quantum leap in terms of knowledge about Mars as a planet really requires human beings."

Many agree with that perspective here at NASA’s First Human Landing Sites/Exploration Zones on Mars Workshop, being held this week at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas. Scientists are pitching about 45 Martian "exploration zones" where multiple crews might land, live, work and explore. These circular zones are 200 kilometers wide, and represent a departure from the single-mission landing spots that have been proposed in the past.

Davis is a workshop co-chair. He's a veteran from NASA’s human spaceflight division "on loan" to the agency's Science Mission Directorate, SMD. His counterpart is Ben Bussey, the chief exploration scientist of NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, HEOMD. Bussey spent the past 12 years as a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory before joining NASA last December.

In many ways, Bussey and Davis’s swapped roles—the scientist as engineer, and vice versa—symbolize what they hope to accomplish at the workshop, and what may need to happen between NASA’s science and human spaceflight divisions in order to get astronauts to Mars. The workshop itself was jointly paid for by SMD and HEOMD.

"I think one of the most important things to come out of this is just instigating dialogue between the science and engineering communities," Bussey said.

So far, it appears to be working. After a day of opening talks, site selection presentations began late Tuesday afternoon and are continuing through Thursday. Each presenter gets 15 minutes to show what their exploration zone, or EZ, has to offer in terms of science and resource-laden "regions of interest." Presentations are given in blocks of four, with time for audience questions afterwards.

A wide variety of EZs have been proposed across the planet, with sites limited to within 50 degrees latitude of the Martian equator. EZs have been pitched inside the Valles Marineris canyon system, along with returns to more familiar regions like the landing sites of the Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity rovers.

Since many of the engineering details behind human Mars landings remain fuzzy—such as how exactly humans will harvest water from the surface—all sites remain on the table for now. "It was never the intention to have a prioritized list of EZs from this workshop," Bussey said. "Part of this was to see how well the community thinks the concept of an exploration zone works."

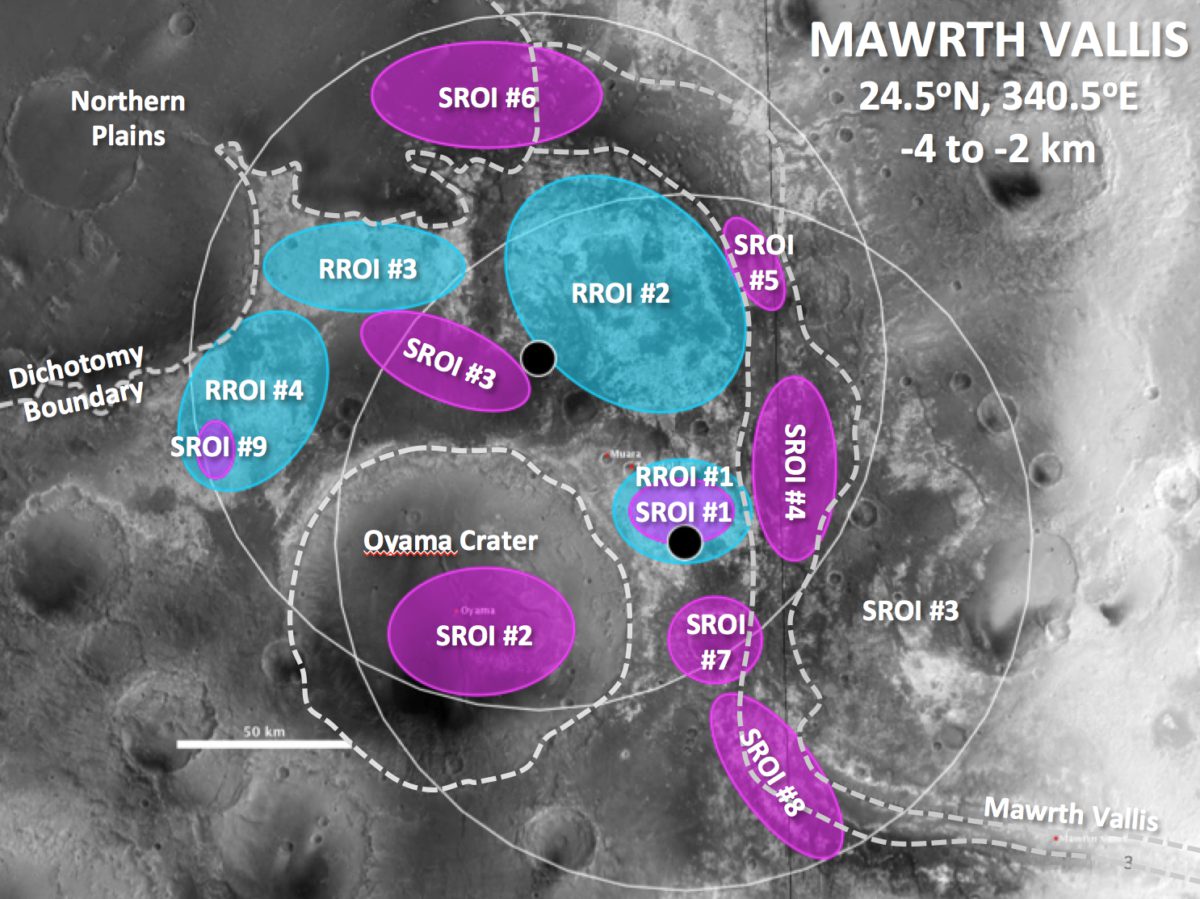

Briony Horgan, an assistant professor of Earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at Purdue University, proposed an exploration zone in Mawrth Vallis. She said that in order for the human exploration of Mars to become a reality in the 2030s, the space community needs to start working on developing the necessary technology now.

"In order to design that technology, the engineers need to know what the terrain astronauts would be living on and traversing over looks like, and what kinds of materials they need to figure out how to process to extract resources," she said. "Meanwhile, the geologists need to know what landing sites are realistic so that we can get and analyze enough data with existing orbital assets to make compelling cases for science, safety, and resources."

There is no shortage of questions to be answered before a landing site can be selected. But two looming decisions revolve around how to best utilize NASA’s current and future Mars assets. First, there’s the question of how the space agency's existing instruments—including the powerful HiRISE camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter—can help.

"From my perspective, a key part to come out of this is what MRO imaging we want to request," Bussey said. "MRO is a very valuable asset and we want to make sure we are are only asking for things that are the highest value."

Secondly, there’s a growing realization that MRO won’t be around forever. The stalwart spacecraft launched more than ten years ago, and both scientists and human exploration advocates are starting to consider what might come next for high-resolution Mars reconnaissance.

On Tuesday, Rich Zurek, the chief scientist for JPL’s Mars program office, pointed out that for robotic landing sites like Curiosity in Gale Crater—which had a 20-by-seven-kilometer landing ellipse—MRO’s HiRISE camera has, over time, been able to blanket the site with high-resolution imagery. But Zurek said it would take 400 HiRISE images to cover just one proposed EZ.

Another looming question is how to best characterize the amount of water available for humans at a potential landing site. "The issue of where water is and how you can quantify that it's really there—and be sure it's really there when you start sending landers—is probably the central issue that you'll see develop over the next year or so," Davis said.

Some proposals call for baking hydrated minerals—essentially rock or sand with water locked inside—to supply astronauts with water for consumables and rocket fuel. A less energy-intensive process is tapping into ice sheets just below the Martian surface, but these sheets are typically only stable at mid-Martian latitudes, farther from the equator. Furthermore, it can be difficult to characterize the amount of available ice with a high degree of certainty.

"And that's probably not going to be answered with our current data capability," Davis said. "It will probably require something else to get us there."

One idea floated at the workshop is a new orbiter to be launched as soon as 2022. The spacecraft would use solar-electric propulsion, a technology already earmarked for some of NASA’s early Mars plans. "The beauty of SEP," Davis said, "is that when you get to the Mars system, you don't need to accelerate any more—it’s basically free power." The surplus energy could be used to supply a suite of advanced instruments, including a radar system capable of better characterizing ice sheets below the surface. But a new orbiter could take more than five years to develop, and no official plans are on the books yet.

Regardless of what happens next, an air of cautious optimism seems to dominate the conference. Discussions between presentations are lively, and both Davis and Bussey are pleased that the science and human spaceflight communities are starting to work together towards a common goal.

"There's a humility that comes with it," Davis said, "because you realize you don't know a lot, and you have to learn it, and I think that makes it easier to build bridges, which is what this effort is about."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth