Jason Davis • Jul 07, 2015

Pushing Back the Frontier: How The Planetary Society Helped Send a Spacecraft to Pluto

Bill Nye felt a little uncomfortable.

Maybe his signature bow tie was a little tight that day. Maybe he was still adjusting to regular life following the end of his “Science Guy” television show. Or maybe it was because he was hefting a huge bag of postcards through U.S. Senate offices in Washington, D.C.

It was October 2000. Scientists and space fans had lobbied for more than a decade to send a spacecraft to Pluto, the last, unexplored classical planet in our solar system. Each time a proposed mission made it past the drawing board, it was scrapped for political or budgetary reasons. The latest spacecraft proposal, Pluto Kuiper Express, made it all the way to the instrument selection phase. But with costs pushing the $1.1 billion* mark, NASA canceled a Pluto mission—again.

Editor's note: This article will be published in the next issue of The Planetary Report.

*All cost figures have been converted to 2014 dollars.

The postcards in Nye’s arms came from ten thousand members of The Planetary Society. All urged Congress to overturn NASA’s decision. Flanking Nye was The Planetary Society’s then-executive director Louis Friedman, who cofounded the space advocacy group with Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray in 1980. Nye was vice president of the board of directors—but he hadn’t really signed up for the job. It was more like he was drafted. “This was a job you got when you leave the room when everybody's drinking,” he recalled. “You come back, and they say, ‘You’re the vice president!’”

Nye and Friedman planned to highlight public interest in a Pluto mission by hauling the postcards around Capitol Hill, delivering half to Representative Dana Rohrabacher and half to Senator Bill Frist—both of whom chaired powerful space science committees.

The Congressional mail dump was just one salvo in a long, bitter fight over Pluto exploration that culminated with the launch of the New Horizons spacecraft in 2006. And though it was an Atlas V rocket that ultimately sent New Horizons out of Earth orbit, the mission would not have been possible without the dogged persistence of countless scientists, space fans, and advocacy groups. Among the latter was The Planetary Society, always striving to help NASA to push back our solar system’s frontier.

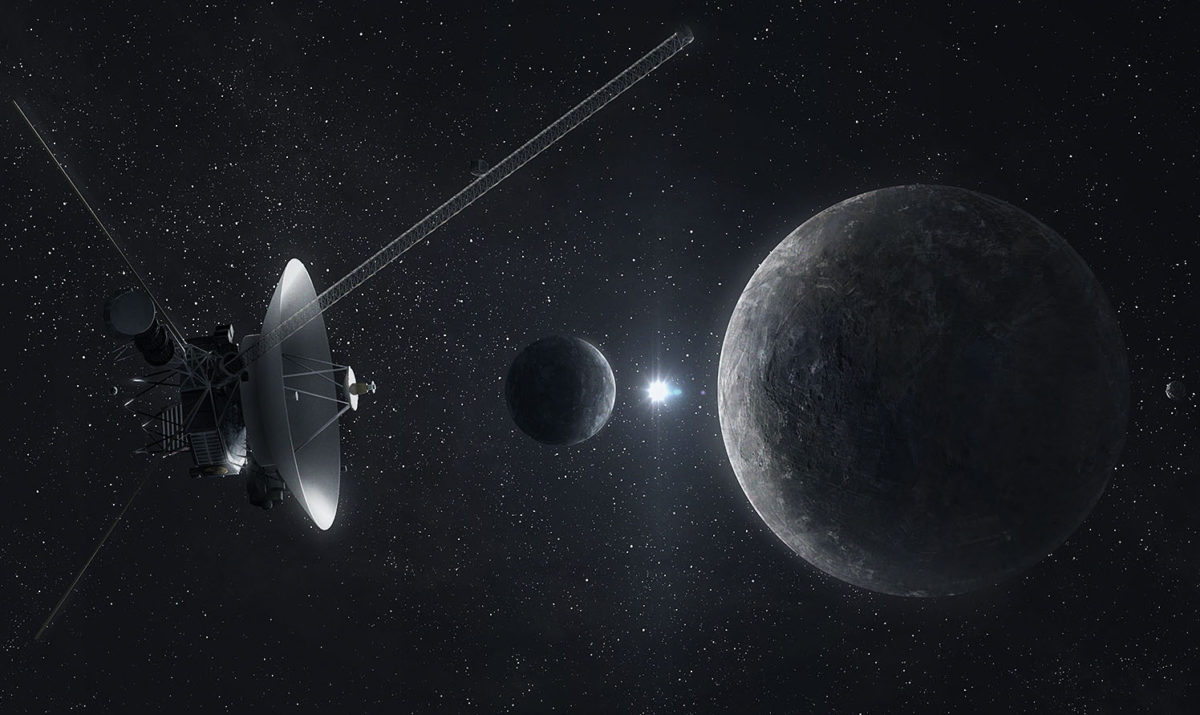

In 1989, Voyager 2 whizzed past Neptune, skimming the ice giant’s atmosphere by just 5,000 kilometers. With that encounter, eight of our nine classical planets had been visited by spacecraft. Two years later, the U.S. Postal Service released ten stamps commemorating the history of planetary exploration. Each planet—along with Earth’s moon—got a stamp featuring a spacecraft that visited that world. Pluto’s stamp had no spacecraft. Its caption simply read, “Not yet explored.”

It almost didn’t turn out that way. When Voyagers 1 and 2 were sent on their respective tours of the solar system, NASA considered sending Voyager 1 to Pluto after the spacecraft’s Saturn encounter. But the flyby path that would bend Voyager’s trajectory toward Pluto precluded a visit of Saturn’s moon, Titan, a tantalizing world in its own right and the only moon in our solar system known to have a stable atmosphere.

“Voyager-Pluto was a real possibility,” said Jonathan Lunine, a Cornell University astronomer who helped define Pluto mission objectives in the 1990s. Lunine, speaking to reporters at a 2014 New Horizons briefing, said the decision to fly past Titan was critical in gaining support for future Saturn missions. “Without the Voyager-Titan mission, it would have been very hard to make the case for the Cassini-Huygens mission—arguably one of the most successful planetary missions in history,” he said.

By 1990, scientists were starting to float ideas for Pluto missions. An early, audacious concept called for a miniature spacecraft weighing only 40 kilograms, slated for a speedy 5- to 6-year trip. The idea was scrapped when shrinking down a set of usable science instruments for the small craft proved to be unfeasible.

That same year, another Pluto concept appeared in the pages of The Planetary Report, the Society's quarterly member magazine. The article, “Pushing Back the Frontier: A Mission to the Pluto-Charon System,” was co-authored by NASA’s Robert Farquhar, and Alan Stern, a planetary scientist from the University of Colorado, Boulder. Stern unveiled a slimmed-down version of Voyager with four science instruments and a total weight of 350 kilograms. Bearing a price tag of $543 million, the spacecraft would launch by 2003 and reach Pluto in 14 years. The concept became known as Pluto 350, named after the spacecraft’s target weight.

Pluto 350 never came to fruition, but Farquhar and Stern’s article appeared in the homes of one hundred thousand Planetary Society members. It was the start of a long campaign for Pluto exploration that ultimately culminated with the appointment of Stern as the principal investigator of the New Horizons mission.

“The Planetary Society gave continued, strong support for a whole variety of different Pluto missions that never made it off the drawing board,” said Stern. And while everyone from school children to the National Academy of Science ended up helping get the spacecraft off the ground, “The Planetary Society was always there—no question.”

By 1991, a new spacecraft design called Mariner Mark II was being developed for missions to the outer solar system. The vehicle was slated for NASA’s upcoming Cassini mission, which would orbit Saturn and drop a probe into Titan’s atmosphere.

NASA considered sending a Mariner Mark II to Pluto. The spacecraft’s probe would separate en route, passing Pluto a little more than three Earth days after the primary vehicle. Since Pluto’s rotational period is six and a half days, the planet’s previously unlit side would be facing the Sun, allowing Mariner Mark II to map Pluto’s entire globe.

In terms of cost and complexity, Mariner Mark II was a drastic departure from Pluto 350. Launching on a mammoth Titan rocket, it weighed two tons and came with a price tag of $3.2 billion. It didn’t take long for NASA to realize Pluto mission concepts were headed in the wrong direction.

In 1992, a third Pluto mission concept materialized and brought back the ambitious miniature spacecraft from 1990. Dubbed Pluto Fast Flyby, a pair of small, lightweight probes would launch atop two of the beefy Titan rockets proposed for Mariner Mark II. One spacecraft would arrive a year ahead of the other, giving scientists insight into Pluto’s seasonal changes.

As it was for Pluto Fast Flyby’s miniaturized predecessor, shrinking down the science instruments proved difficult. The two spacecraft gained weight, creeping up to 140 kilograms each. And the cost of the Titan launchers alone was $1.3 billion, giving the mission a total price tag of about $2.1 billion.

While Pluto Fast Flyby was cheaper than Mariner Mark II, it still wasn’t cheap enough for NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin. In a 1994 issue of The Planetary Report, Louis Friedman reported that Planetary Society officials met directly with Goldin to lobby for the mission. “Dan Goldin expressed great interest in the Pluto proposal,” Friedman wrote, “but tempered his enthusiasm with concern that the cost of the mission would prevent it from ever being done.”

With the launch vehicle consuming more than half the mission cost, The Planetary Society went looking for cheaper rides. They found one: Russia’s Proton rocket, available at the bargain price of just $47 million.

“At the time we floated this proposal,” wrote Friedman, “NASA was not permitted to consider joint missions or Proton launches. ‘Well,’ we thought, ‘maybe NASA couldn’t consider such things—but The Planetary Society could.’”

By the time the Society approached Russia, the Pluto Fast Flyby concept had been trimmed to a single vehicle. Russia proposed adding a small probe that would plunge through Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere before crashing into the surface. On Valentine’s Day 1994, the Society delivered the proposal to NASA. Wes Huntress, the head of NASA’s space science division, was intrigued. Furthermore, he saw an opportunity to pair Pluto Fast Flyby with another long-delayed spacecraft: Solar Probe.

Solar Probe was a daring mission to capture direct measurements of our Sun’s corona. Getting there required a gravity assist at Jupiter, where the spacecraft would whip back toward the inner solar system. Since Pluto Fast Flyby also required a Jupiter gravity assist, Huntress wanted both missions to fly on Proton rockets. The similarities between the two trajectories might ultimately save costs. The project was called “Fire and Ice,” a literal description of the probes’ destinations and an allusion to thawing relations between Russia and the United States. In a letter to The Planetary Society, Huntress wrote:

“I believe the interest demonstrated by your membership in such a bold venture is shared by the majority of the American public. We believe that too, and if we work with the Russians to lower costs and pool expertise, an exciting program like Fire and Ice could be popular enough to succeed.”

But at the time Huntress lauded The Planetary Society’s initiative, NASA’s planetary science program was reeling from an embarrassing mishap. In August 1993, the agency inexplicably lost contact with Mars Observer—a Mars-bound probe that was just three days away from entering Martian orbit. Had Mars Observer arrived safely, it would have been the first successful spacecraft at Mars since the Viking missions in 1976.

Alan Stern, who was making his own push for NASA to team up with the Russians, believes the loss of Mars Observer dampened NASA’s enthusiasm for a Pluto mission. “These events began to sour then-NASA Administrator Goldin on Pluto Fast Flyby,” wrote Stern in a paper summarizing the history of Pluto mission concepts.

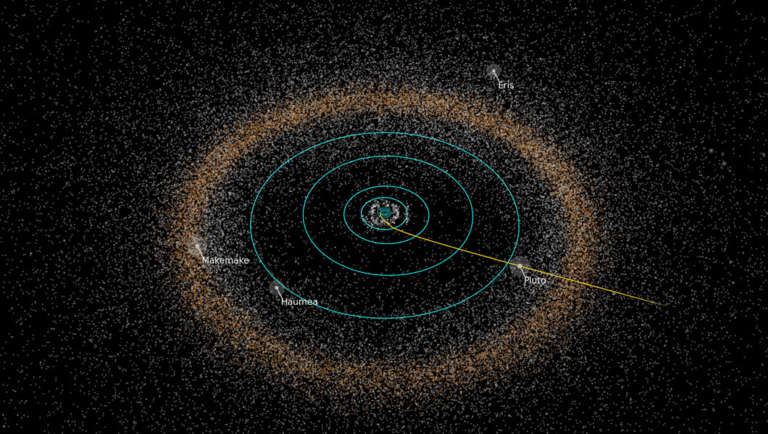

With the project stalled again, fresh support arrived from an unexpected source: Pluto’s neighbors. In 1992, astronomers began discovering new worlds beyond Neptune’s orbit. The list grew, confirming the existence of the so-called Kuiper Belt, a band of icy objects at the edge of our solar system. Pluto, it seemed, was one of the largest members of this new group. Scientists had many questions about these new Kuiper Belt objects—questions that could be answered only by visiting spacecraft.

In 1995, NASA rebranded the languishing Pluto Fast Flyby mission as Pluto Express, and upped the weight allowance to 175 kilograms. The mission’s name evolved to Pluto Kuiper Express, reflecting the goal of having the spacecraft visit an additional Kuiper Belt object after the Pluto flyby. “However,” wrote Stern, “in late 1996 Pluto Kuiper Express mission studies were drastically cut back by Administrator Goldin and no instrument selection was initiated.” In 2000, NASA canceled the mission, which had grown in cost to $1.1 billion.

It was the fourth time in ten years that a Pluto concept was nixed. The Planetary Society sprang into action, mobilizing the postcard campaign that ultimately sent Bill Nye, Louis Friedman, and a small mountain of mail to Capitol Hill. “The Planetary Society really made a cause célèbre out of it,” said Stern.

Congress took notice. Representatives James Walsh and Alan Mollohan, the ranking members of the House Appropriations Committee, sent a letter to Goldin asking why Pluto Kuiper Express had been cancelled. The NASA Advisory Council also voiced its support for a Pluto mission. By the end of the year, NASA announced it would accept new Pluto mission proposals.

The tide reversed in early 2001, when the newly inaugurated President George W. Bush’s administration released its first budget request. There was no line item for a Pluto mission—effectively canceling it. The Planetary Society called for congressional hearings. The scientific community applied behind-the-scenes pressure. And by September, about $40 million had been added back into the budget for spacecraft development and launch vehicle selection, keeping the Pluto campaign alive.

In the meantime, NASA narrowed the number of spacecraft proposals to two. One concept, dubbed New Horizons, came from a team led by Alan Stern, now the director of space studies at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. Mission control would be located at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Baltimore, Maryland.

That November, Stern attended the annual meeting of the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society, held in his hometown of New Orleans, Louisiana. He received a phone call from NASA informing him that New Horizons had been selected for further development. “A win party was held on Bourbon Street that night in the New Orleans French Quarter,” wrote Stern, “but the details remain understandably fuzzy.”

But the fight still wasn’t over. In 2002, the fiscal year 2003 budget request was released. And although Congress had allocated $40 million for Pluto mission studies during the previous year, NASA’s new budget showed a zero for Pluto—again.

It wasn’t all bad, though. The new budget also announced the creation of a new line of midsize missions called New Frontiers. More expensive than small, Discovery-class missions but cheaper than Flagship programs, a New Frontiers-class spacecraft could cost up to $855 million. New Frontiers missions would be prioritized according to the Decadal Survey, a report outlining the country’s top priorities for space science. The Decadal Survey is produced every ten years by the National Research Council, the working group of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. The next Survey would cover exploration goals from 2003 through 2012.

Early versions of the report were published in 2002. The message was clear: the top priority for NASA’s New Frontiers program should be a mission to Pluto. NASA and the Bush administration could no longer oppose the mission. “They couldn’t turn down the National Academies,” said Stern.

The Planetary Society and other groups lobbied Congress to restore New Horizons funding for the fiscal year 2003 budget request. Wesley Huntress, the NASA associate administrator who had supported the Society’s 1994 Valentine’s Day proposal to fly to Pluto via a Russian rocket, was now the Society’s president. Huntress wrote Congress in support of increasing NASA’s budget to accommodate the Pluto mission. The Planetary Society followed Huntress’s appeal with a petition of 10,000 signatures.

Finally, in 2003, when the 2004 budget request was released, $167 million was allocated to the New Frontiers program. The fate of New Horizons was secure. Humanity would get an up-close look at Pluto.

“Status check.”

“Go Atlas.”

“Go Centaur.”

It was a peaceful January afternoon in 2006 on the Florida coast. An Atlas V rocket sat quietly on the pad at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 41. Suddenly, a deluge of water flooded the pad’s flame trench, and the engine ignition sequence whirred to life.

“Five, four, three, two, one,” counted a NASA television commentator. “We have ignition, and liftoff of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft on a decade-long voyage to visit the planet Pluto—and then beyond.”

Armed with its maximum contingent of five solid rocket boosters, the Atlas V rose quickly. It pierced the clouds within seconds. With the help of an additional third-stage engine, New Horizons became the fastest object ever to leave Earth orbit. It arrived at Jupiter just one year later, picking up a gravity assist that put it on course for a July 2015 Pluto flyby.

It has been 25 years since Alan Stern’s Pluto 350 mission concept was unveiled in the pages of The Planetary Report. From petitions and postcards to engineering design and persistent scientists, it truly took a village to raise a spacecraft.

Stern thinks the history of New Horizons is an important tale for scientists and space advocates who have eyes on their own ambitious missions. “I think the really interesting human story,” he said, “for people who might want to tackle something like getting a spacecraft to Uranus or Neptune, is that you have to really want it. There are many more good ideas than there is money to go around.”

For The Planetary Society, New Horizons shows that persistence pays off. Never underestimate that a group of dedicated space fans can, as Bill Nye says, “change the world.” It’s a principle that hearkens back to the Society’s origins, he said. “This mission to Pluto is really part of the Carl Sagan legacy—to explore the solar system.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth