Jason Davis • May 29, 2015

For LightSail Test Mission, Waiting is the Hardest Part

This morning, The Planetary Society’s LightSail spacecraft flew past Hawaii, heading northeast from Australia to Canada, over what looked like an interminable stretch of ocean. The CubeSat had just reached its 702-kilometer apogee, and was beginning a long, bending dip toward Earth. About 45 minutes later, off Africa’s Atlantic coast, it bottomed out at 355 kilometers, and began climbing again.

LightSail hasn’t talked to Earth in seven days. Its engineering team is waiting out a suspected software glitch, hoping for a cosmic ray-induced reboot that should restore the spacecraft’s radio. In the meantime, long-duration simulations to recreate the freeze-up problem are running on BenchSat, LightSail’s deconstructed, acrylic-mounted clone. Long chains of e-mails shoot back and forth, riddled with tech speak that crosses the boundary of understanding for most outsiders. “Auto-ranging is a step in initializing the 5042. The driver polls the chip until the step is complete. Sometimes it takes longer than the fixed number of iterations in the poll loop,” reads one exchange. “I was poking at satcomm possibly accessing an incorrect value instead of the proper frequency,” was the response.

There has been an outpouring of reactions—mostly positive—from the public. People write in with helpful ideas. A couple suggestions contained Linux file redirection tricks that would circumnavigate the need for a reboot. I passed those ideas to the team, only to learn testing has shown the radio is probably squelched altogether. Even the most ingenious of IT hacks won’t work—no matter what we say, LightSail doesn’t appear to be listening.

Some kind Australians with governmental email addresses wrote in to say they heard LightSail. I decided not to get too excited, and in the end, that was the right decision—subsequent analysis by Cal Poly San Luis Obispo showed the signal didn’t match. The Australians probably picked up one of the other CubeSats in LightSail’s fleet, chirping at a similar frequency.

On Monday, the Joint Space Operations Center began issuing two-line element sets—dual number strings used to plot a spacecraft’s orbit—for all of the ULTRASat cubes. I started squirreling the data away in a Google document, regularly plugging it in to a software package called Orbitron. JSPoC only tells us there are ten objects floating around the Earth; they don’t track down which is which. Doing so requires input from each CubeSat team—decoding doppler shifts in your telemetry chirps, for instance, can help you figure out which spacecraft is yours. Unfortunately, LightSail is no longer chirping.

That doesn't deter me from picking at what little information I have, so I plug each day’s updated TLE set into Orbitron and see which object most closely matches LightSail’s trajectory from P-POD deployment. From a visual standpoint, we match closely with ULTRASat2.

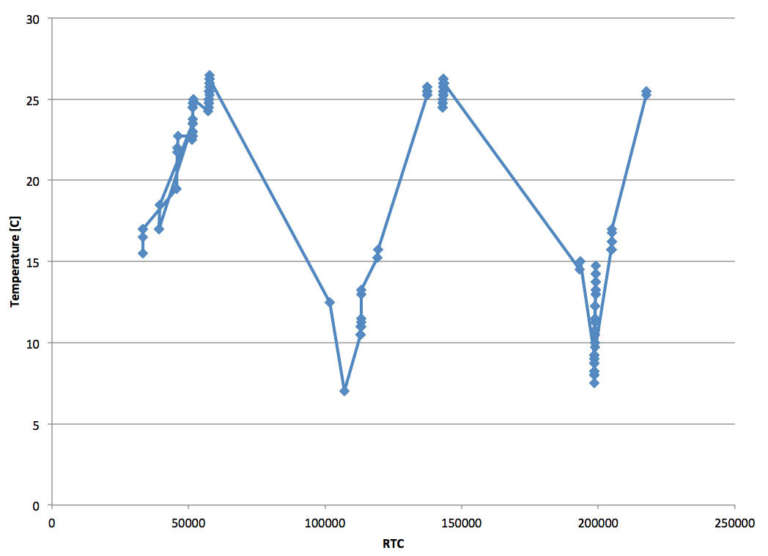

I also play with the data packets we received from LightSail until the loss of contact. Due to the attitude control system bug that was discovered shortly before launch, a lot of the juicier information is frozen in time from four seconds after deployment. Some interesting data points that aren’t include battery levels and temperature readings from the main system board. Plotting these out yields a spiky little mountain range.

You can trace those peaks and valleys back to individual packets, pull out the UTC timestamp, and use Orbitron to see where the spacecraft was at the time. At one of the peaks—26.5 degrees Celsius—LightSail had just finished bathing in sunlight, and was about to cross into darkness.

At one of the valleys—7 degrees—the spacecraft was emerging from Earth’s shadow. You might also notice these data were collected when LightSail was in range of a U.S. ground station—either Cal Poly or Georgia Tech.

And so, as we enter flight day 10, the waiting continues. It’s the hardest part, according to Tom Petty, but our CEO, Bill Nye, says he can hang in for a few more weeks. As for me, I’ve stopped obsessively refreshing the packet repository where new LightSail data appear, thanks to our systems administrator, Brandon Schoelz. Brandon, sensing my discontent, volunteered to create a script that texts me when new packets are received. We tested it, and Brandon is very good at this sort of thing, so I have no doubt it will work the moment LightSail reboots and phones home. Even if it doesn’t, I’ll be among the first people that the engineering team notifies.

This morning, I plucked my phone off my nightstand. No texts. No emails. LightSail was silent.

I opened my phone’s browser and checked for new data anyway.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth