Bill Dunford • Mar 09, 2015

A Sky Full of Stars

Where are the stars?

This is one of the most common questions I hear about images from deep space. For example, look at this recent picture postcard of the Earth and the moon sent by China's Chang'e-5 T1 spacecraft.

It's a striking portrait of a handsome couple. But if they are floating in space, where are the stars? Shouldn't we see thousands of stars in the background, maybe even the Milky Way? This solid wall of black sky in so many images from space is the source of confusion--not to mention conspiracy theories.

The answer is pretty straightforward. The stars are there. In fact, if you could physically ride along with Chang'e or any of the other spacecraft you'd see the stars in all their glory. The issue is a photographic one. Cameras have a much more difficult time than your eyes do when it comes capturing widely different levels of light. It's simply very difficult, often impossible, to correctly expose a photograph when the scene contains both very bright areas and very dark ones. A simple experiment: try taking a picture of a bright moon in a dark sky. Chances are, even though you can see both the moon and the stars with your eyes, if you've set up your camera to expose the picture so that the moon shows up clearly, you won't see any stars near the moon's bright disc in your picture.

So when the Apollo astronauts were bouncing across the moon's brilliant horizon the sky behind them looked black. The same is true for images from robotic spacecraft in deep space: Saturn is dazzling, not only aesthetically but physically as well.

All that said, there are exceptions. Sometimes, those exceptions make for the most amazing images. When conditions are just right the stars do show up, as in this view of Saturn's moon Enceladus from the Cassini spacecraft.

This shot was possible because the moon is not lit by brilliant sunshine, but only by reflected light from Saturn.

Here's another look at Enceladus. Here, the camera was set so that the sunlit side of the moon is awash in overexposed light, but the plumes from its famous ice geysers and the stars in the background show up just fine. As Cassini tracks Enceladus over the course of several photographs, the moon moves in its orbit and the stars appear to rush by.

Even farther out in the solar system, the gas giant planet Neptune is graced with a whisper-thin set of rings. When the Voyager 2 mission passed by, controllers set the cameras to expose for the faint ring arcs, allowing the stars to appear as well.

And one of my favorites, a view of Saturn's odd, two-sided moon Iapetus. Again, we're looking at the moon's night side, illuminated only by reflected Saturnshine. The long exposure has stretched the stars into a shower of light.

Stargazing in deep space has its practical uses, too. One way to precisely measure Saturn's rings is to watch when they pass in front of a bright star. As the star shines through the translucent circles of icy ring particles, scientists note how it flickers bright then dim, allowing them to refine their model of the ring's properties.

When we look at the sky from Earth, the planets themselves look like bright stars, simply because they're so far away. The same is true of spacecraft observing planets other than the ones they're currently orbiting. Here's a view of Venus from the Clementine mission to the moon. From its vantage point near the Earth, Clementine's cameras saw Venus as the bright evening star we know so well.

The same is true for other planets.

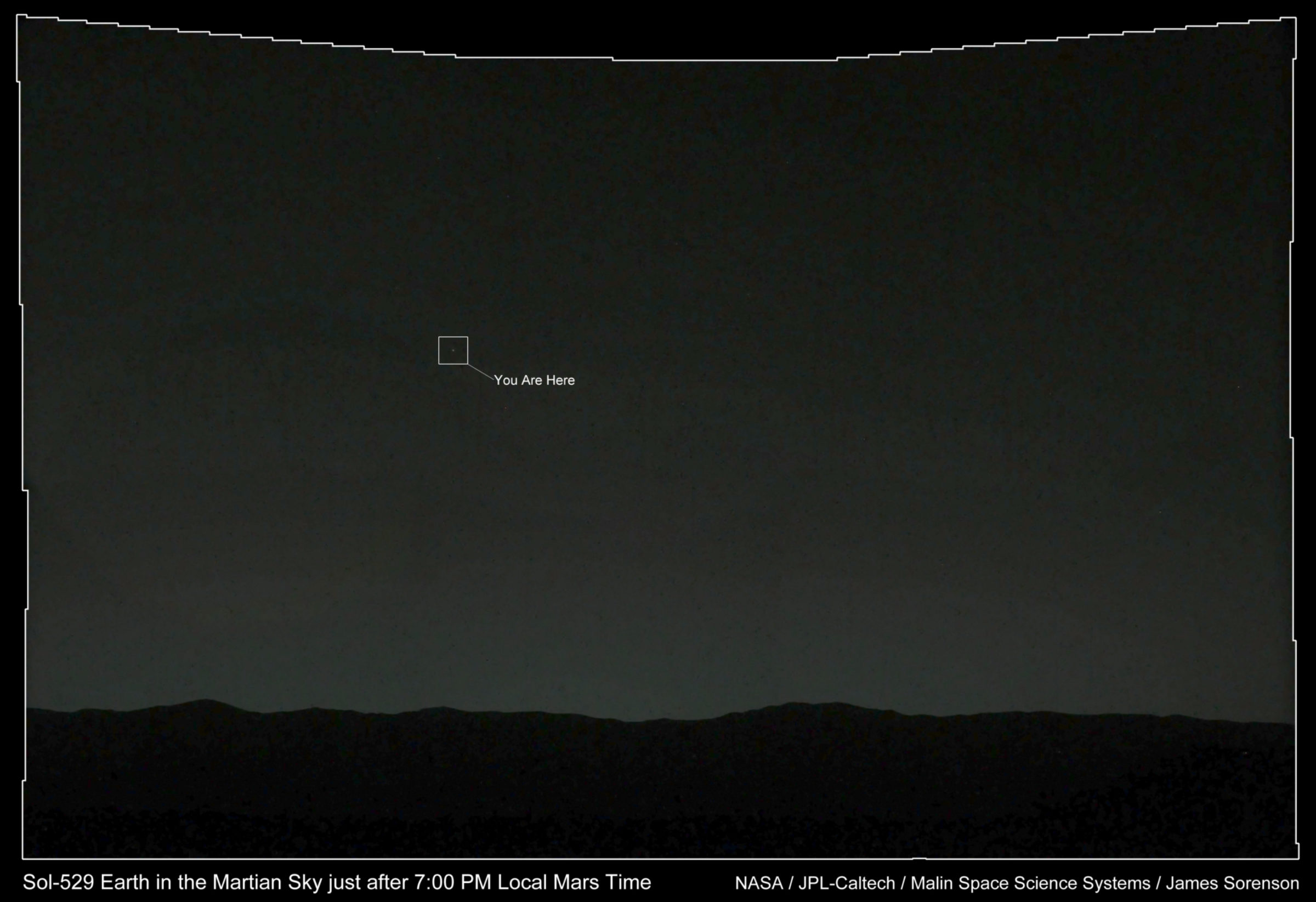

On January 31, 2014, about an hour and a half after sunset, a robot on Mars raised its head. It lifted its camera eyes from the desert floor, and stared off toward the west. There, a darkening sky spread out above a line of silhouetted mountains. In the perfectly clean air, the stars began to ignite one by one. The brightest was actually two stars, a brilliant white gem and a smaller spark just below it.

But they weren’t stars at all. They were the Earth and the Moon.

Mars may be an alien world, but if you went there and looked up at the night sky you’d see something that might surprise you: most of the stars would look exactly the same. The distance between the Earth and Mars isn’t nearly enough to change the perspective on the much more distant constellations. You’d see all the familiar sights, the Big Dipper and Orion and the Milky Way. The only difference in the sky, other than the sharp brilliance of everything seen through such thin air, would be that “extra” evening or morning star and its little companion.

You would look at that spark, and you would know you weren’t alone.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth