Jason Davis • Feb 06, 2015

FOIA Request Sheds Light on NASA Mission Extension Process

It all started with a tweet.

Green: The proposal submitted by Erickson and Grotzinger for Curiosity extended mission is at http://t.co/j5JyvCB185 — Emily Lakdawalla (@elakdawalla) September 11, 2014

I was half-working, half-watching Twitter last September as a team of scientists behind the Mars rover Curiosity hosted a live press briefing to announce they'd "arrived" at Mount Sharp, the giant hunk of rock in the middle of Gale Crater. Curiosity coverage is Emily's domain, so I wasn't paying close attention. But since she used capital letters—VERY interesting—I clicked the link. It was the Curiosity team's extended mission proposal, submitted to a planetary science senior review panel in April 2014.

View document: 2014 Curiosity extended mission proposal

NASA science missions have finite lifespans that are defined long before a spacecraft leaves the launch pad. The Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity, for instance, were slated for 90-day missions. Spirit ended up lasting seven years, and Opportunity is still going strong after eleven.

These days, mission planners usually expect a spacecraft to outlast its warranty. But if they want to keep going beyond the spacecraft’s prime mission, they have to ask NASA for more money. It's required by law, in fact; every two years, spacecraft operators pitch their extended mission proposals to an independent group of academics and other space experts. These senior review panels, as they are called, are used for missions in all four of NASA's science divisions: Earth science, astrophysics, heliophysics, and planetary science.

In Curiosity's case, the 2014 extended mission proposal went to a planetary science senior review panel led by Professor Clive Neal at the University of Notre Dame. After some additional back-and-forth, the panel presented its findings to Jim Green, the head of NASA's planetary science division. Here are the results:

| BUDGET | GUIDELINE | RECOMMENDED |

|---|---|---|

| Mission | Rating | Rating |

| Cassini | Excellent | |

| LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) | Very Good/Good | Excellent/Very Good |

| Opportunity | Excellent/Very Good | |

| MRO (Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) | Excellent/Very Good | |

| MEX (Mars Express) | Good/Fair | Very Good |

| ODY (Mars Odyssey) | Very Good/Good | Very Good |

| Curiosity | Very Good/Good | Very Good/Good |

The "guideline" column represents the review panel’s rating based solely on the proposals. For LRO, Mars Express, Odyssey and Curiosity, the review panel recommended changes to the proposals, and if those changes were accepted, the ratings would improve those listed in the "recommended" column.

At the time of the report, NASA still didn’t have a fiscal year 2015 budget, as the government continued to operate under stopgap continuing resolutions. With the passage of the CRomnibus in December, that changed, ensuring all seven missions would continue to operate through September 2015.

On Monday, Feb. 2, NASA released its 2016 budget request. And while the news was largely positive—a long-awaited mission to Europa finally received a green light—there was also a downer included for fans of LRO and Opportunity: neither mission received funding for fiscal year 2016. That means as it stands, both missions have just seven months of operations left.

There will certainly be a push to save both missions as the budget request passes through the House and Senate. And as Casey Dreier explains, Opportunity was in a similar situation last year and ended up getting funding. But it begs the question: Why did LRO and Opportunity—which both received ratings of Excellent/Very Good—get singled out for the chopping block, while three lower-rated missions survived?

For now, that question remains unanswered. But it highlights the fact that to outsiders, the mission extension review process is at best confusing, and at worst—with oddly adjectival ratings like “Very Good/Good”—arbitrary.

When the planetary science senior review report was made public in September 2014, it made headlines for an entirely different reason: its harsh criticism and low rating of the space community's darling, Curiosity.

"NASA hurls insults at Curiosity, the world’s favorite rover," was the headline at the Washington Post. "NASA Curiosity Rover Missing ‘Scientific Focus And Detail’ In Mars Mission: Report," said Universe Today. "Curiosity Rover Science Plan Slammed by NASA Review Panel," wrote our own Casey Dreier. It turned out the review panel wasn't very fond of the Curiosity team's extended mission proposal. The authors wrote:

"Despite identification of two EM1 [Extended Mission 1] science objectives, the proposal lacked specific scientific questions to be answered, testable hypotheses, and proposed measurements and assessment of uncertainties and limitations."

Ouch. And what did the panel think about the team itself, including the chief scientist, John Grotzinger?

"Unfortunately the lead Project Scientist was not present in person for the Senior Review presentation and was only available via phone. Additionally, he was not present for the second round of Curiosity questions from the panel. This left the panel with the impression that the team felt they were too big to fail and that simply having someone show up would suffice."

Too big to fail? Was Curiosity a bank, or a rover?

View document: 2014 Planetary Science Division senior review panel report

Just a week later, the Curiosity team convened a press conference to talk about all the good science the rover had been doing, and all the good science it planned to do. And to top it off, the team announced Curiosity had reached the foothills of Mount Sharp—even though most people thought the rover was still a few kilometers away.

While many assumed the press briefing was a response to the review panel’s criticism, Grotzinger denied there was any connection. Emily Lakdawalla later explained that the Mount Sharp arrival declaration wasn't without merit—though it seems hard to believe the team wasn’t, at the very least, a little more motivated than usual to present their findings.

Which brings us back to Emily's tweet: Why were we just now seeing the 2014 Curiosity extended mission proposal?

@elakdawalla That review proposal looks totally FOIA-able. I bet we could have been looking at it since April, if we'd known to ask :)

— Jason Davis (@jasonrdavis) September 11, 2014Reporters covet access. Getting access to the right person or document can make your story look different than everyone else's—especially stories that are largely driven by press releases or news conferences. So when reporters see a document materialize they wished they'd seen a long time ago, it drives them crazy.

NASA is a government agency. Your tax dollars fund it, and as a U.S. Citizen, you have a right to know what it's doing. Since 1967, this right has been exemplified through the Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA. FOIA compels government agencies like NASA to publicly disclose everything from extended mission proposals to Administrator Charlie Bolden's emails. There are restrictions and exemptions, and it can be difficult and time-consuming. But in general, anyone—journalist or not—can submit a FOIA request.

NASA can say no if the law allows it. Recently, I submitted a FOIA request for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program source selection document. This paper outlines the reasons NASA picked Boeing and SpaceX over Sierra Nevada to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station. Since then, a version of the document has been released to the public. But at the time, my request was denied, with NASA reasoning the document contained proprietary commercial information.

FOIA requests need not be antagonistic, though many government agencies view them that way. You can always ask nicely instead, and in many cases, that's a better option. I know of a journalism professor that encouraged his entire class to flood a sheriff's office with FOIA requests for information that might have been disclosed after a simple meeting or phone call. The sheriff was not pleased.

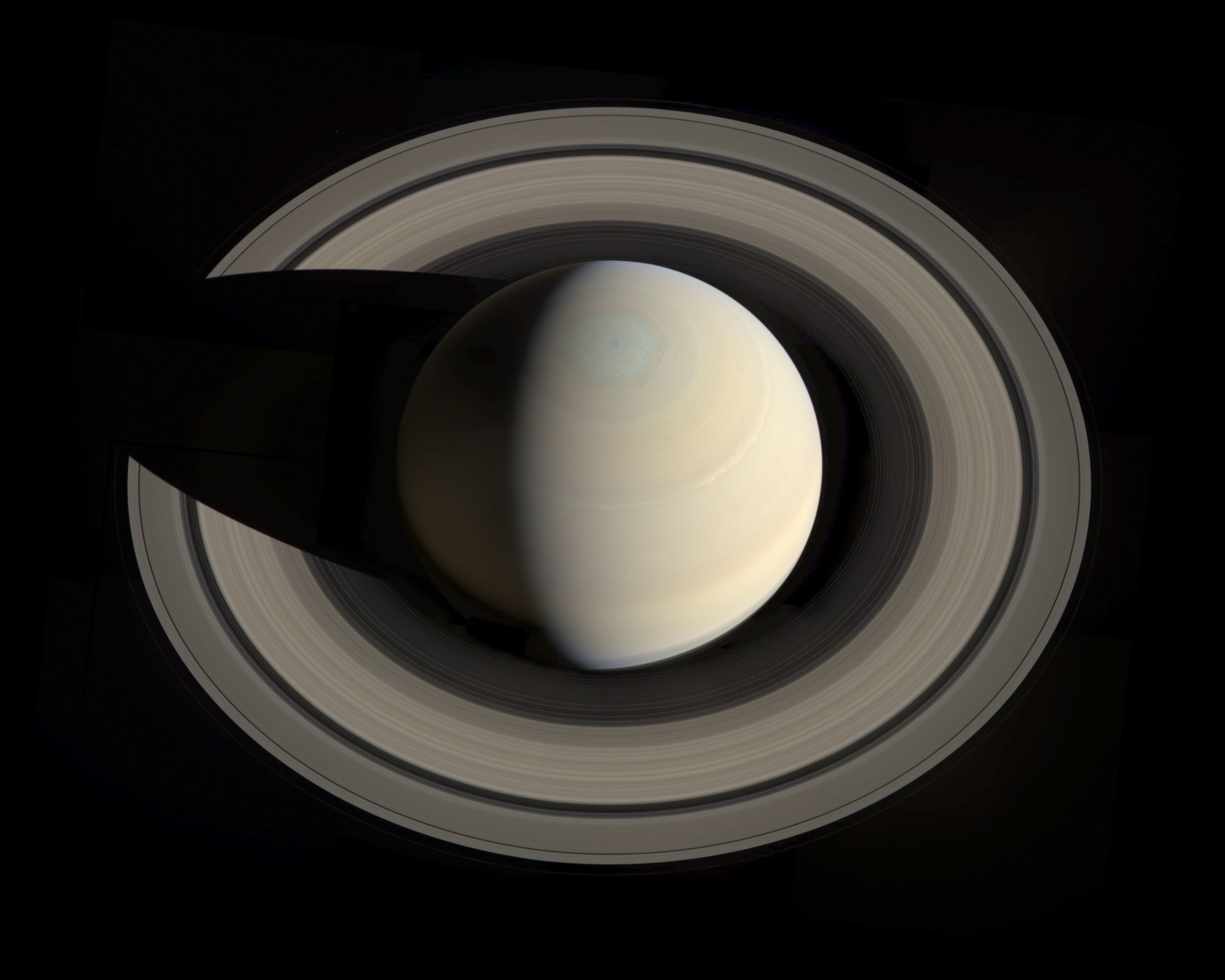

After the Curiosity team released their extended mission proposal, we were able to see for ourselves whether the review panel's critiques were justified. But a few of us at The Planetary Society started wondering what the other extended mission proposals looked like. The review panel gave Curiosity a rating of "Very Good/Good." Cassini, NASA's flagship spacecraft currently cruising around Saturn, got a grade of "Excellent." It all seemed a bit mysterious. What made Cassini so much better?

Unfortunately, we couldn't compare the Curiosity proposal with the Cassini proposal because we couldn’t find the Cassini proposal posted anywhere online. We asked around, but not a single person seemed to have a copy—including some very senior scientists who were actually responsible for authoring the report. Additionally, we couldn’t find the 2012 version of the Cassini report, nor could we get ahold of the 2012 planetary science senior review panel report.

Time for a FOIA request.

What followed was a long back-and-forth between myself and NASA's FOIA office, mostly clarifying which documents we were talking about. In the end, The Planetary Society shelled out $125.40 for "duplication fees" to get the Cassini proposals. The fees were assessed in spite of the fact that I was physically mailed original PDFs of the documents on a CD-ROM with a hand-written label. In NASA's defense, FOIA fees are uniform across government agencies. But this is why most people don't bother with FOIA requests: they're tedious, they require a rudimentary understanding of the law, and they often result in the requester having to pay money.

View document: 2012 Cassini mission extension proposal

View document: 2014 Cassini mission extension proposal

We didn't have to pay for the 2012 senior review panel report. NASA responded to that portion of our request by having it posted on the Lunar and Planetary Institute's website, where planetary science subcommittee documents are kept.

View document: 2012 Senior review panel report

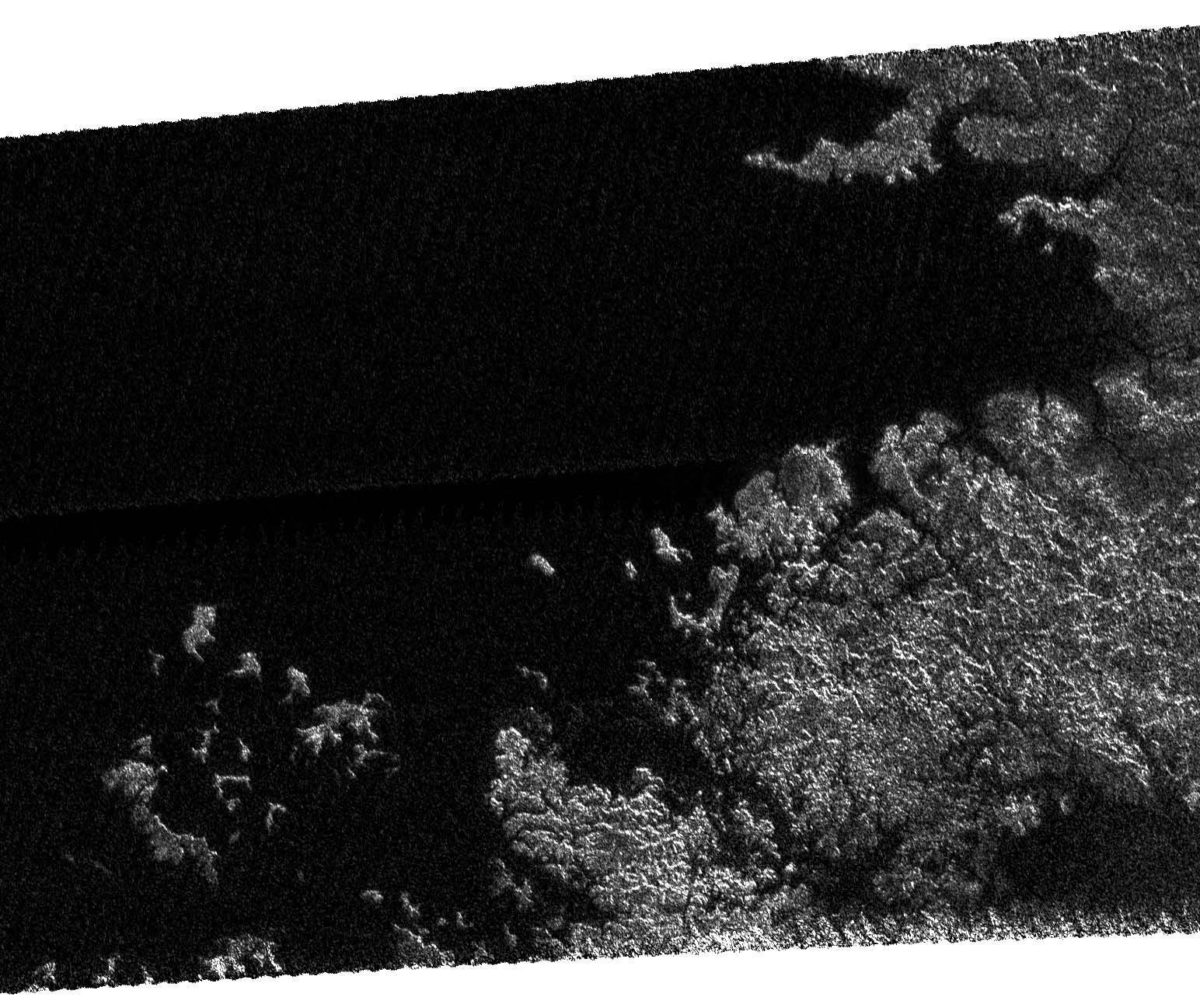

The 2014 Cassini extended mission proposal is 563 pages. The senior review panel usually looks at a condensed, 20-page version; that's the page count for the Curiosity proposal that was released. Since Cassini is slated to plunge into Saturn's atmosphere and end its mission in 2017, the team was allowed to make a 30-page, three-year proposal. The format of the first 30 pages of the Cassini proposal roughly matches the Curiosity report. Basically, the team talks about what their mission has accomplished, and what is expected to be accomplished in the extended mission.

There are quantifiable differences between the Curiosity and Cassini reports. The first is the amount of pages the teams spend patting their spacecraft on the back, versus looking ahead. The Curiosity report dedicates just 6 of 20 pages, or less than one third, of their report talking about the extended mission. The rest of the report is largely dedicated to recapping the rover's past successes. Cassini, on the other hand, uses 20 of 30 pages, or two thirds, of their report talking about the future.

Secondly, the Cassini report beats Curiosity in terms of the sheer number of science objectives planned for its extended mission. Cassini proposes 17 new science objectives for its final three years of life, grouping them into subcategories: Titan, Icy Satellites, Rings, Magnetosphere and Saturn. Curiosity, on the other hand, has 10 science objectives, but just two are new to the extended mission. The other eight are continuations of investigations that began during the rover's prime mission. Even when accounting for differences in mission duration, 17 vastly outweighs two.

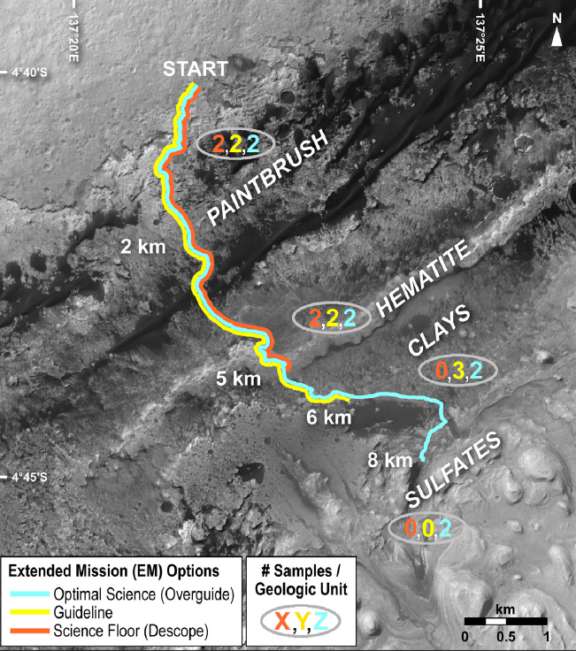

Is it right to impugn the Curiosity report solely on these numbers? Not necessarily. These are two very different types of missions. Curiosity is expected to travel a maximum of eight kilometers over the next two years, stopping to conduct field observations at up to four distinct geological regions. Cassini, on the other hand, will be whipping around Saturn, buzzing Titan and other satellites before making 22 death-defying orbits between the rings and the planet.

And though Cassini’s orbital path is complex and varied, this actually helps the science team with planning. They know what they are going to encounter, and when. Curiosity, on the other hand, has to rove to a new field site, look around, and figure out what it’s going to do.

What, then, about the review panel's original critique that the Curiosity proposal lacked scientific questions and testable hypotheses? As mentioned, Curiosity will visit up to four, distinct geological "units" over the next two years, named paintbrush, hematite, clay, and sulfate. The proposal discusses the value of sampling each unit, along with what appear to be testable scientific questions. Here are some excerpts from each (emphasis added):

Paintbrush:

"...it is possible that these rocks form a completely different rock package from what overlies them; possibly, it represents an older sequence of stratified rocks that has been complexly deformed, possibly by impact events along an unconformity surface, before being overlain by undeformed strata. Alternatively, it may represent something like slump-folded fine-grained rocks, such as mudstones. It seems unlikely to be crater central peak or peak ring material because it is off-axis and at an elevation higher than what might be predicted. However, each of these hypotheses is testable with Curiosity."

Hematite:

"Emplacement of the hematite is hypothesized to result either from exposure of anoxic Fe2+-rich groundwater to an oxidizing environment, leading to precipitation of hematite or its precursors, or from in-place weathering of precursor silicate materials under oxidizing conditions. These hypotheses and implications for habitability will be testable with Curiosity."

Clay:

"Clay minerals are generally regarded as favorable exploration targets for habitability and preservation of organics. In terms of habitability, at Yellowknife Bay, they indicate relatively neutral pH, which opens the range of possibilities for potential microbial metabolisms. Beyond that, it would be difficult to predict more from orbit [...] Consequently, we strongly advocate sampling the clay unit in Curiosity’s search for habitable environments and preservation of organics."

Sulfate:

"Sampling across the clay-sulfate transition is an extraordinary opportunity to test models of taphonomy and environmental history."

The flare-up over the senior review panel findings eventually reached the NASA Office of Inspector General, or OIG, which is charged with providing agency oversight. The OIG looked into the extended mission review process used for each division of NASA's entire Science Mission Directorate, which includes Earth science, astrophysics, heliophysics, and planetary science.

View document: OIG Report IG-15-001

There were problems. While the OIG had recommendations for all four science branches, the planetary science division received extra scrutiny, mostly related to the budgetary process. The OIG said every science division except planetary science submits extended mission proposals that project out to five fiscal years. By contrast, planetary science extended missions only include two years in their proposals—the timeframe required by law.

Additionally, planetary science extended mission proposals appear to suffer from budget uncertainties. The run-up to the review process works roughly like this: Prior to the proposal phase, a spacecraft team does preliminary work with NASA to determine how much money they'll need for their extended mission. In the case of Earth science, astrophysics and heliophysics, the proposals must use this agreed upon budget number as a baseline.

For planetary science, however, that budget number can change. And apparently, it can change at the last minute with little or no explanation, sending a spacecraft team scrambling to revise their proposal. From the OIG report:

"Several project officials also stated they did not have sufficient time between receipt of the budget target and the proposal due date. Finally, they voiced concern that while they were able to begin writing their technical proposals without final budget guidelines, the time allotted to respond may not have been reasonable."

The OIG report focused on NASA’s Science Mission Directorate review process—not the 2014 planetary science senior review report itself. Regardless, Professor Clive Neal went on the offensive. He crafted an open letter in response, arguing there's a reason budgets can change at the last minute:

"The budget situation for the Planetary Science Division over the last two PSD Senior Reviews has fluctuated wildly (including a ~20% drop in the President’s request for Planetary Science over 1 year). It is my opinion that PSD has managed the budget expectations as well as could be expected. This situation is compounded when Congress fails to pass spending bills and NASA is forced to operate under a Continuing Resolution. I found the criticism that resulted in this recommendation to be unfounded given the uncertain budgetary environment."

John Grunsfeld, the head of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, mostly agreed with the OIG's recommendations for improving the review process. He said future planetary science extended mission proposals would be told to stick with previously agreed-upon budget numbers, except in an extenuating circumstance—like a last-minute spacecraft instrument failure.

The Science Mission Directorate also plans to make other OIG-recommended improvements, such as synchronizing the budgeting process across all science divisions—including planetary science. Grunsfeld’s team also plans to review its proposal guidelines to make sure all expectations are clearly articulated. The changes should be in place for the next review cycle, scheduled for 2016.

But what of the original kerfuffle? Is Curiosity still doing valid science? Or is it aimlessly trekking through the foothills of Mount Sharp, a rover too big to fail?

At face value, Curiosity's extended mission proposal wasn't as strong as the proposal from its flagship brethren, Cassini. The Curiosity team may have benefited from a longer discussion of their plans, or by more clearly defining discrete science objectives.

But the testable scientific questions are there. Maybe this was simply just an editing problem. Maybe a last-minute budget shift threw things into disarray. Or maybe drilling into rocks doesn't seem as exciting as soaring under the rings of a gas giant.

"Dance like nobody's watching, sing like no one is listening, science like your peers aren't reviewing."

— SarcasticRover (@SarcasticRover) December 22, 2014In any case, Curiosity treks onward. Since the review spat, the rover paused to snap a picture of a comet. It is conducting a detailed walkabout of an area called Pahrump Hills. And it continues to catch the occasional whiff of methane coming from…somewhere. Oblivious to the bureaucratic wrangling back on Earth, our one-ton Martian ambassador carries on, sol after sol, pecking at the surface of Mars. With its arrival in the foothills of Mount Sharp and its prime mission complete, Curiosity is finally becoming the field geologist it was always meant to be.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth