Bill Dunford • Jul 21, 2014

One Day on Mars

Mars glows, both as a copper-colored spark in the sky and as a destination for the imagination. It’s almost strange to remember that the planet is an actual place, that the mountains and plains of Mars are just as solid as the ground beneath your own street.

We’re the first people in history who are able to appreciate this firsthand. Well, secondhand anyway, thanks to our robots. They are bathed in very real red dust even if we can't get our own boots dirty just yet. In all the Solar System, Mars is special in that it is the adopted home of more mechanical Earthly immigrants than any other world. It has enough active explorers, in fact, that we can see the ground-level, almost-real-time reality of the place in a striking way. Right now, there are three orbiters in service, with two more en route, and two rovers, with a new lander under construction and additional missions at various stages of development.

On June 27 of this year, all of the active missions at Mars were observing the planet. But thanks to just two of them, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and the Mars Science Laboratory (Curiosity), we can really zoom in on the planet, just by using images that were taken on that one day.

MRO carries several cameras, including the Mars Color Imager (MARCI). On June 27 MARCI took in a global view of the planet, as it does every day. Across the Martian surface, the color of dried mud, it was easy to see weather typical for this time of year. High, thin clouds of water ice formed over the tropics and clung to the peaks of ancient volanoes. In the south, the seasonal advance of the polar ice cap brought with it weather fronts that kicked up immense dust storms. Traveling at 25 meters per second (about 56 mph), storm fronts came close to Curiosity's location at Gale Crater (marked with a white dot below) but in the end never hit there with force.

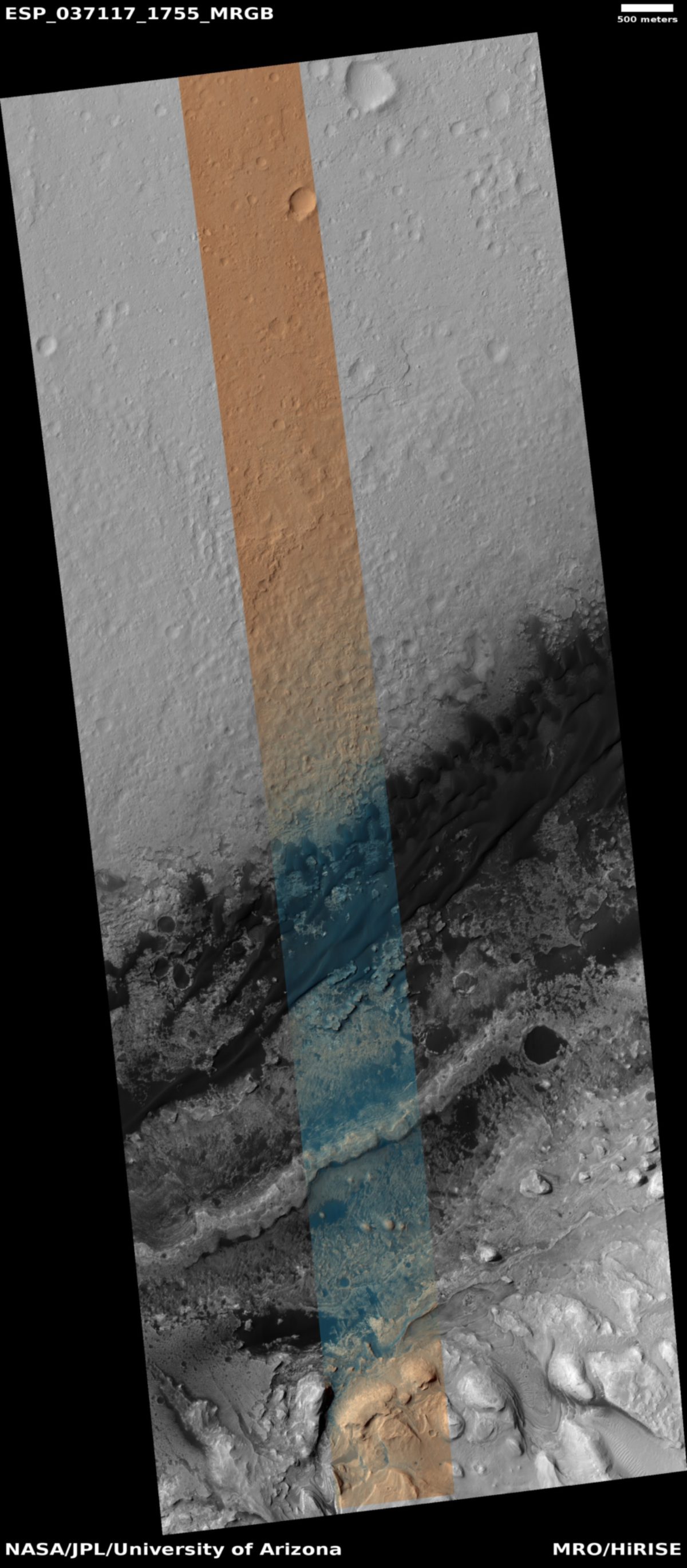

MRO carries another camera called HiRISE, which took a much closer look at one section of Gale Crater. On June 27, HiRISE observed part of a relatively flat plain in the northern part of the crater, along with a complex landscape of dunes, mesas, and cliffs at the base of the crater's central peak, Mt. Sharp. Those canyons and buttes contain the history of Mars in layered sandstone like the pages of a book, and they are the ultimate destination for the Curiosity rover.

In fact, Curiosity itself makes an appearance in this very image. Zoom way in, follow the tracks as they weave between craters, and there it is.

When MRO snapped this shot, it was passing over the rover at a distance of 277 kilometers (173 miles). It was 3:44 in the afternoon, local time, and shadows on the ground were beginning to lengthen. Amazingly, objects as small as 83 centimeters across can be distinguished in the full-resolution version of this image.

As if it weren't remarkable enough that one robotic spacecraft photographed another on Mars, this image carries additional significance. It captures almost the exact spot where, after a Martian year of working and driving, Curiosity first crossed outside its landing ellipse. This is the area that engineers targeted with a high level of calculated confidence for the probe to touch down when it arrived. The landing ellipse was chosen for the safety of its relatively flat expanse more than for its scientific interest. Now that Curiosity has driven past this frontier, its most ambitious adventures await.

We get to ride along. Here's a shot of almost this same moment, taken by Curiosity on the ground.

Ripples of sand, pioneer tracks, stark hills in the distance. Not so different from the deserts of Earth. Now it's easier to see Mars as a place where you could walk and feel the ground beneath your feet (even if you had to bring your own air with you).

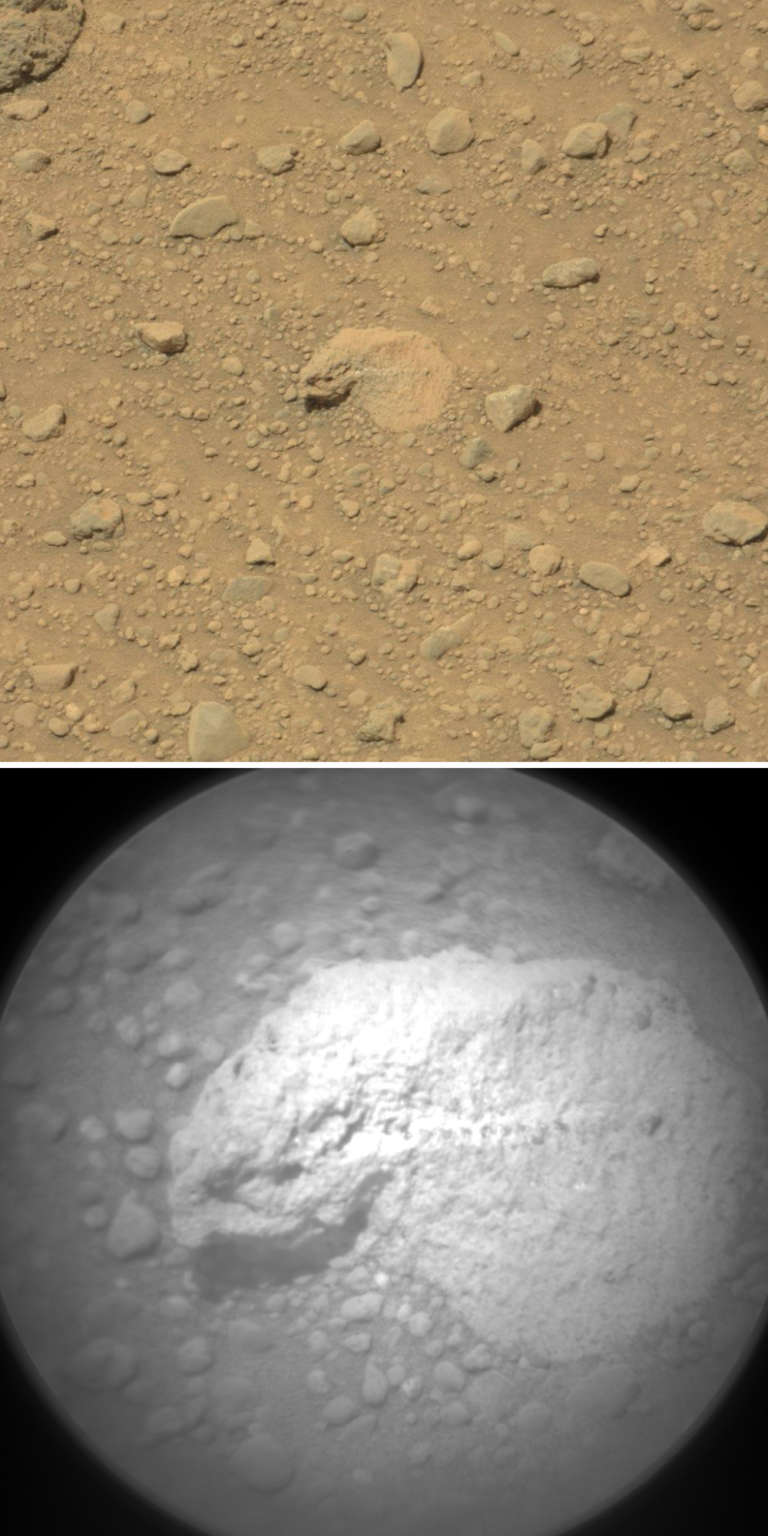

Always searching for scientific clues, Curiosity gets even closer to the soil, though. Here's a closeup of small rocks found near the rover on the same day, with one stone near the center that peaked the interest of mission scientists. What often happens to rocks like that is they get shot with a laser. A device on the rover's "head" emits short bursts of laser light that vaporize tiny puffs of material from the rock, which are then observed by the ChemCam Remote Micro-Imager for analysis. That's the camera that captured the second image below.

This is the closest view of Mars in this series, and it reveals fine details in the pebbles, including a neat, horizontal row of tiny holes blasted out by the laser.

One day people will roll stones like this between their fingers and feel their texture, either because samples have been returned to Earth, or because the people themselves will be standing on Mars. Either way, I imagine that at that moment, Mars will feel even more real.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth