Jason Davis • Jun 06, 2014

After decades of silence, a vintage spacecraft says hello to Earth

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

A group of space enthusiasts and vintage hardware experts walk into a radio observatory. They contact a 36-year-old spacecraft to ask how it’s doing. The spacecraft responds and says it’s well. The group leaves and continues to stay in touch with the spacecraft from their laptops, working out of an old McDonald’s building at the NASA Ames Research Center.

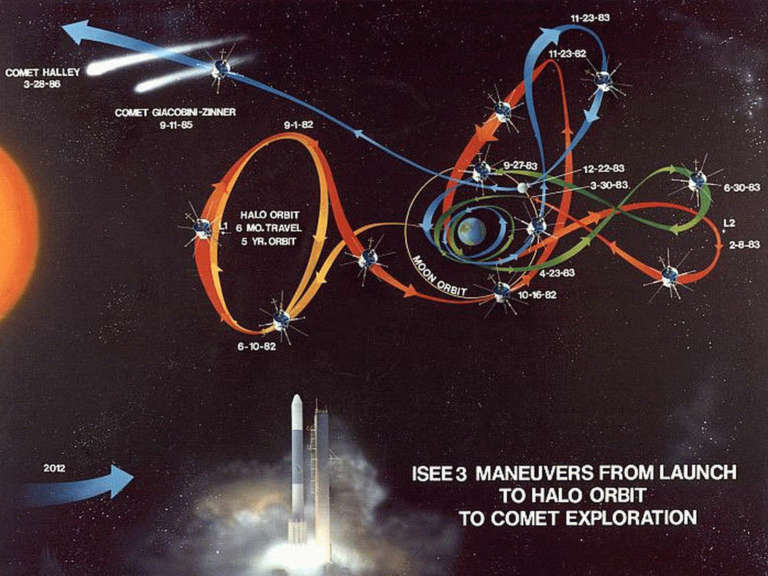

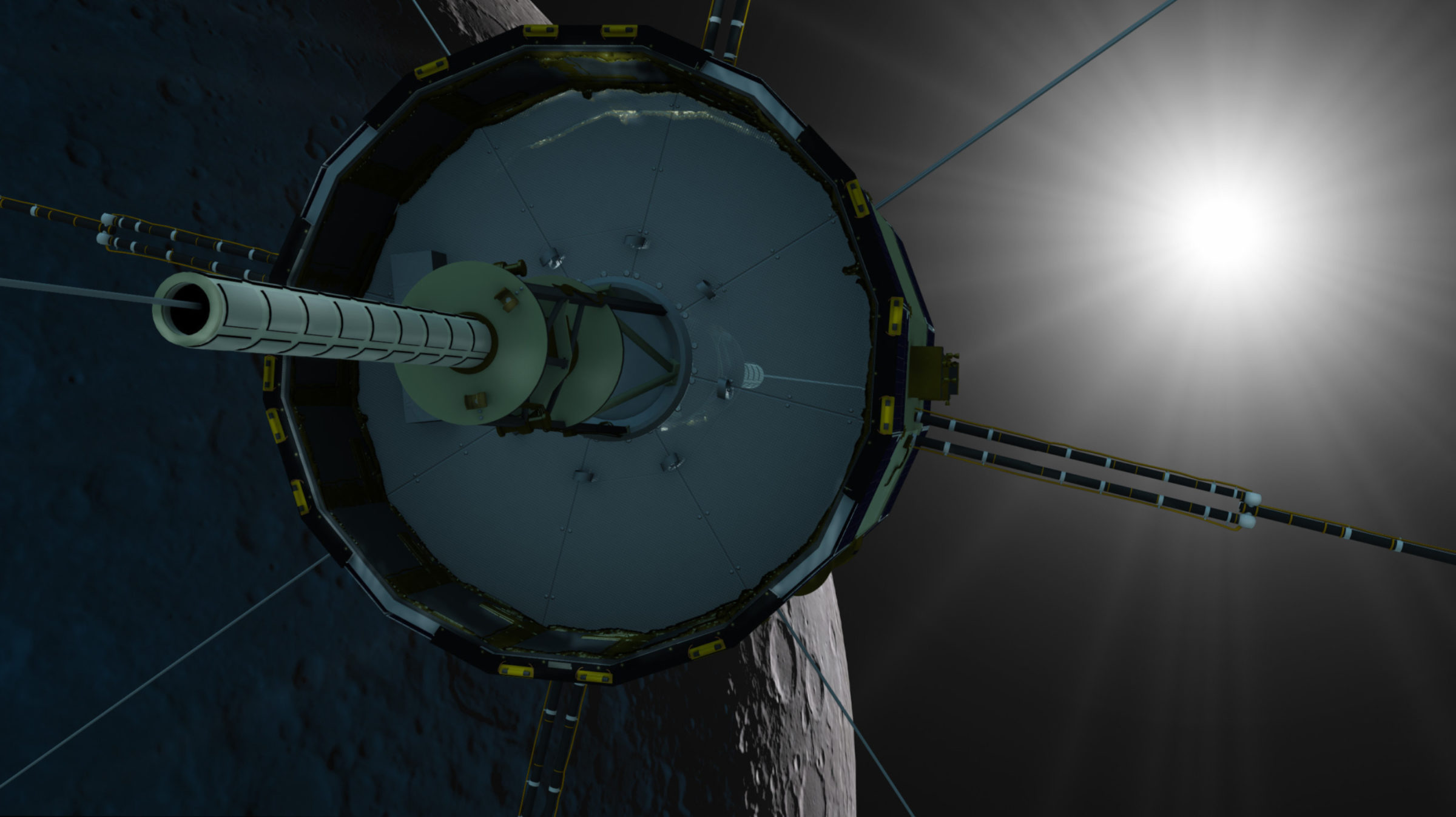

It’s no joke—that’s the latest news coming from the ISEE-3 Reboot Project, a crowdfunded effort to repurpose NASA’s International Sun-Earth Explorer (ISEE-3), launched in 1978 on a mission to study Earth’s magnetosphere. In 1983, ISEE was sent on a new mission to study comets Giacobini-Zinner and Halley, and has been spent the past three decades circling the sun in roughly the same orbit as Earth.

Later this year, ISEE is coming home. It will swing dramatically past the moon in accordance with its original trajectory, and the reboot team hopes to send it on one of several possible new missions. The team is now in regular contact with the spacecraft, which appears to be functioning remarkably well considering the time it has cruised silently through space.

But with a mountain of challenges facing the vintage explorer, there’s hardly time to celebrate. There's less than two weeks to narrow down the spacecraft’s location, coax it into firing its thrusters, and prepare it for an August 10 lunar encounter in which it will buzz the moon’s surface by 50 kilometers.

A groundswell of support

The flurry of ISEE-3 interest began earlier this year as various groups and individuals took notice of the dormant explorer’s return and proposed possibilities for sending it on a new mission. The leading idea became sending it back to into orbit around the Sun-Earth L1 point—a spot located between the Earth and sun—where ISEE could resume its original mission.

Could ISEE be contacted? The initial response from NASA was no—the original hardware required to communicate with the spacecraft was long gone, and it would be too expensive to rebuild the components from scratch.

Keith Cowing, the editor of NASAWatch.com and SpaceRef.com, decided to look for cheaper ways to regain control of ISEE. He spoke with Robert Farquhar, the designer of the spacecraft’s original orbit. He pitched some ideas to John Grunsfeld, the associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. More conversations with the space agency followed.

“They kept not saying no,” Cowing said. “I said to NASA, ‘I’m going to start a crowdfunding project on April 14.’ Suddenly we had a telecon and they did not say no again.”

Cowing teamed up with Dennis Wingo, the CEO of Skycorp, which develops low-cost space technology using creative design and manufacturing processes. It’s not the first time Cowing and Wingo have worked together to recover vintage NASA assets. The duo are the driving force behind the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery project, an effort to restore original photographs taken by the five Lunar Orbiter spacecraft sent to the moon in 1966 and 1967 ahead of the Apollo astronauts. The LOIRP team has recovered and cleaned up numerous unique views of the moon, including the famous first “Earthrise” photo captured by Lunar Orbiter 1 in 1967. Both the Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project and ISEE-3 Reboot Project are headquartered at McMoons, a repurposed McDonald’s located on grounds of NASA’s Ames Research Center.

The ISEE crowdfunding effort, which raised nearly $160,000 through RocketHub, has been called a citizen science effort. Cowing isn’t a huge fan of the term. “Citizen science sounds like a fancy way to say amateurs,” he said. “Bob Farquhar is on our team. Mike Loucks, from LADEE [NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer spacecraft] is on our team. I designed spacecraft back in the day; so has Dennis, so it’s not like we don’t know what we’re talking about.”

After a long effort to cut through remaining red tape, Cowing and Wingo received the official go-ahead from NASA on May 21. The ISEE-3 Reboot Project was permitted to move forward.

How to talk to a 36-year-old spacecraft

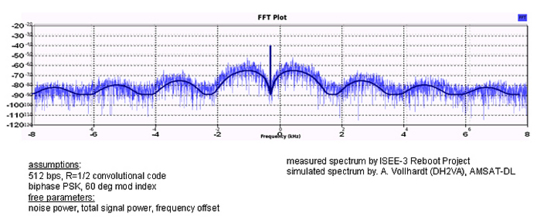

Because the original hardware used to contact ISEE-3 was thrown out decades ago, the ISEE-3 team needed to find a new way to communicate with the spacecraft. They wouldn’t be able to spend the millions NASA was quoting to rebuild original hardware from scratch, so they turned to an alternative: Software Defined Radio (SDR).

“Radios have traditionally been built using ‘black-box’ designs,” said Balint Seeber, an applications specialist and SDR evangelist for Ettus Research, which specializes in the technology. “They are built against specific specifications to serve a specific purpose, and they will only understand or generate signals of a particular kind.”

Seeber was brought on board to help with the ISEE project. He said small SDR boxes are often “orders of magnitude” cheaper than the original hardware they replace. The devices take a raw radio signal and feed it to a connected computer. Using a free, open-source software package called GNU Radio, any run-of-the-mill computer can interpret the signal and decode it according to specifications the user enters. Whereas the interpretation of ISEE's radio signals used to be done using bulky hardware, it can now be achieved virtually.

Likewise, when the ISEE team needs to transmit a command to the spacecraft, they use GNU Radio to input NASA’s original communications specifications. “You feed it the raw ones and zeroes that only the spacecraft knows how to interpret,” Seeber explained. The SDR box translates the ones and zeroes into a radio signal, and sends the signal to a transmitter, where it is beamed into deep space toward ISEE.

All of this requires a really big satellite dish, so the ISEE team teamed up with Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Arecibo is typically used to study astronomical, planetary and atmospheric phenomena, but it is also versatile enough to regain control of wayward spacecraft.

Alessondra Springmann, an Arecibo data analyst that provides observing support, said the observatory helped save the billion-dollar SOHO spacecraft after it spun out of control and lost contact with Earth in 1998. Arecibo was able to bounce a radio signal off SOHO that was received at NASA’s Deep Space Network satellite dish in Goldstone, California.

“With radar, you can determine how fast the spacecraft is spinning,” Springmann said, explaining that in SOHO’s case, NASA was able to determine that “yes, the spacecraft did have fuel, and it was worth their time to recover it.”

Arecibo staff worked closely with the ISEE team to attempt first contact with the spacecraft. Seeber said ISEE is only in range of the radio telescope for about 2 hours and 45 minutes each day. Up until May 29, the ISEE team—along with amateur radio operators around the world—were only detecting the spacecraft’s carrier signal. The carrier signal was ISEE’s automated way of saying it was alive, but it didn’t offer any further information.

The team’s first goal was to command ISEE to begin sending out telemetry—basic information about the probe’s position and health. ISEE has two transponders, A and B, that can receive instructions from Earth. After pouring through old NASA specifications and constructing what they believed were the proper set of commands, the team sent a signal to transponder B, asking the spacecraft to transmit telemetry data.

Nothing happened.

They tried again on transponder A, and an incredible thing happened: the carrier signal coming from the spacecraft changed. ISEE had received the request, correctly interpreted it and did what it was asked. Telemetry came streaming back to Earth. Seeber, along with team member Austin Epps, saw the signal change on their laptops, and Seeber celebrated with a happy dance. “That was the first initial confirmation that our entire system worked,” he said.

You can read Seeber's full explanation of his work with SDR and ISEE-3 in his presentation, "Communicating with a space probe using Software Defined Radio" (PDF).

With the clock ticking, more challenges lie ahead

On August 10, ISEE-3 will buzz the moon at a harrowing distance of just 50 kilometers. As it passes into the moon’s shadow, the spacecraft's solar panels will fall dark, and the probe will lose power for the first time in decades. Its batteries died long ago. Will it wake up when it emerges back into sunlight? There’s no way to know for sure. Surviving the lunar flyby is a prerequisite to whatever new mission Cowing and his team decide to attempt, be it the Sun-Earth L1 point or otherwise.

A major challenge will be narrowing down ISEE’s exact position in order to make the proper trajectory correction maneuver, or TCM. The TCM should ideally happen before mid-June, while the spacecraft remains far enough from the Earth and moon to expend as little fuel as possible to adjust its course.

Cowing’s team has been able to continually refine ISEE’s precise location and heading, or ephemeris, each time they communicate with the craft. But the current uncertainty in ISEE's ephemeris remains large enough that the team cannot say with complete certainty that its current course will not send it crashing into the moon.

One possibility for refining the ephemeris is commanding the spacecraft into what’s known as coherent and ranging mode. Coherent mode, explained Seeber, involves commanding ISEE to lock onto the signals being received from Earth and begin transmitting at a fixed frequency. In ranging mode, he said, “anything you transmit to the spacecraft, the spacecraft will send back at you. You can think of it like a mirror.”

Using coherent and ranging mode, special tones can be sent to the spacecraft that will be bounced back to Earth. As a result, the team can more accurately determine where ISEE is and where it’s heading. Cowing said this technique could involve purchasing time on NASA’s Deep Space Network, which can be configured for this position-finding scenario.

There’s also the more practical matter of commanding ISEE to warm up its hydrazine supply in preparation to fire the spacecraft’s thrusters. Will the heaters work? Can the engines still fire? Assuming the answer to these questions is yes, ISEE should be able to use short thruster bursts to slowly change course. It will take a lot of bursts to put the spacecraft on its proper path.

“It’s like a butterfly flapping its wings to push a wagon down the street,” Cowing said.

The ISEE team is also analyzing information about the spacecraft’s health. On June 5, they reported that all 13 of the spacecraft’s science instruments are powered on. Cowing noted that just because ISEE’s instruments have power, it does not necessarily mean they all work. In fact, he said there is evidence that some do not. Still, the fact that power still courses through the spacecraft’s veins after 36 years is extraordinary.

I asked Cowing if he thinks the ISEE-3 Reboot Project will set a new precedent for NASA projects that the space agency can no longer afford. While he doesn’t expect crowdfunding to solve NASA’s budget woes, he’s optimistic that continued success in projects like ISEE show there are alternative, creative solutions to difficult funding questions. He said NASA’s initial reluctance to get involved with the project is understandable, given recent warnings that a lack of money is endangering the future of missions like the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity.

“If I had the choice between this and Opportunity, it would be Opportunity,” he said. “But why should you have to be facing that choice?”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth