Bill Dunford • Apr 14, 2014

Interview with a Mars Explorer

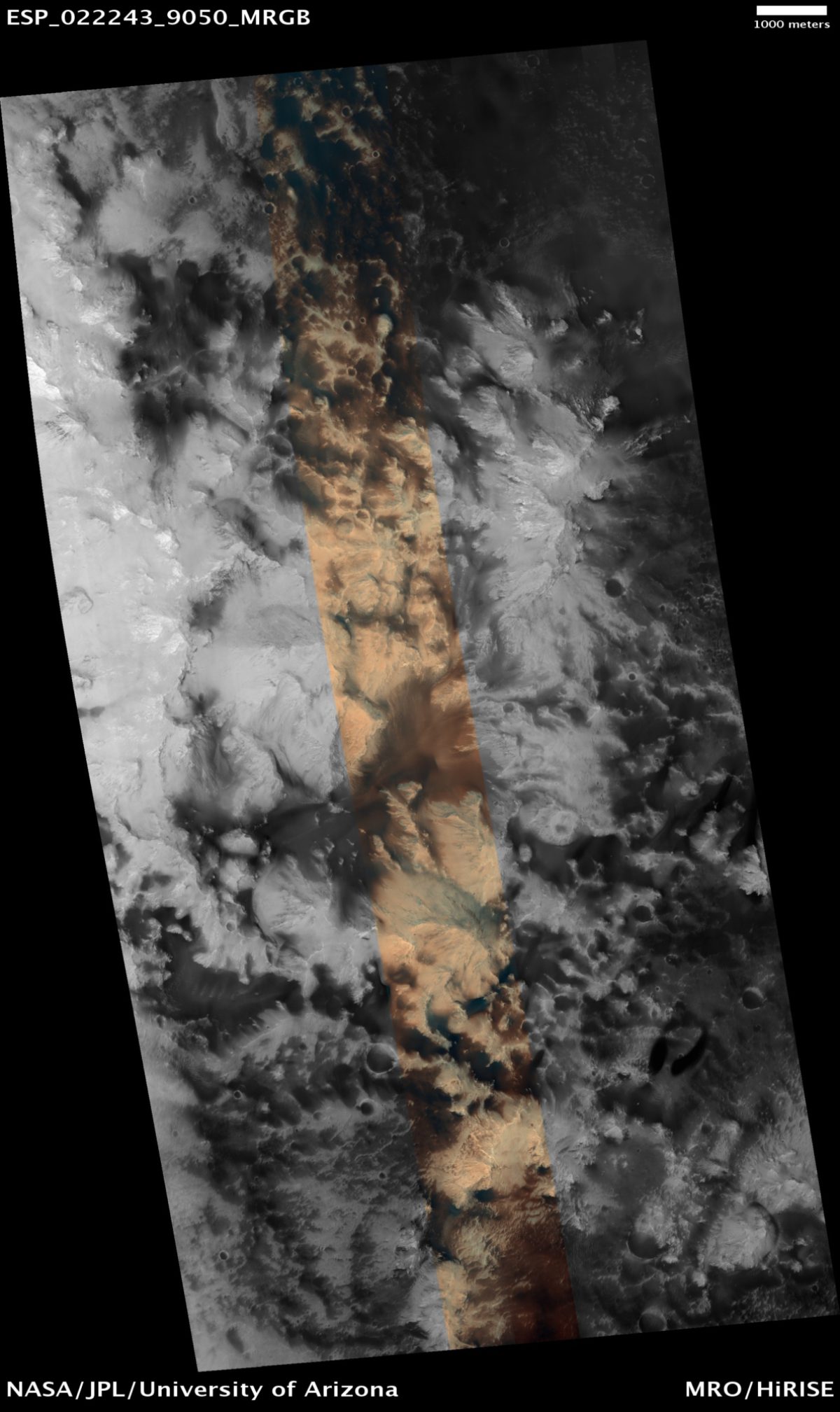

In the end, none of the robotic missions to the planets are really about the robots. All of these expeditions are the work of people living on Earth. Recently, I had the privilege of posing a few questions to one of these explorers, JPL's Dr. Sarah Milkovich. She's the Investigation Scientist for HiRISE, the sharp-eyed camera on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) that I wrote about last week.

Can you choose a favorite HiRISE image?

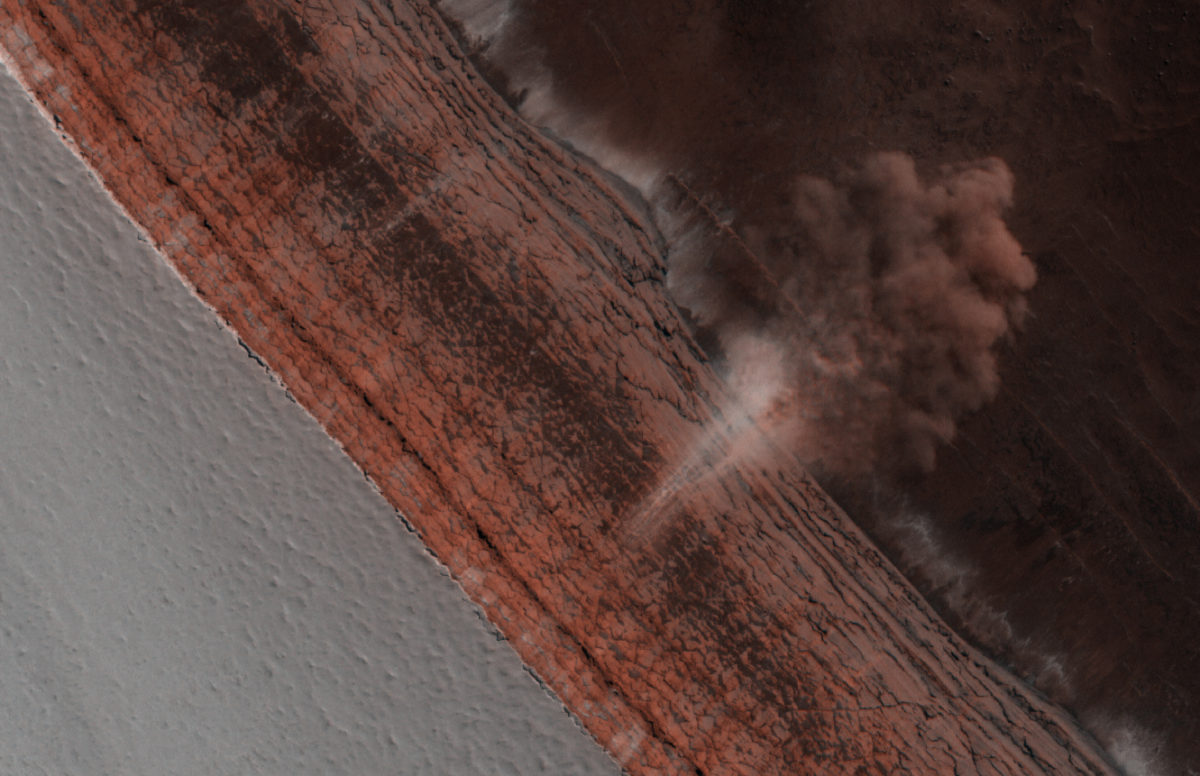

I am very fond of the north polar avalanche pictures, because the polar deposits are my favorite places on Mars—that's what my research is on—and the avalanches were just such a complete surprise. You really have to be in the right place at just precisely the right time to see them. We've seen them every northern spring ever since entering orbit.

Is there a "most underrated" image? One that you love but were surprised when it didn't get more attention?

The HiRISE images are such an integral part of Mars research today; we're very appreciated by the Mars community!

It is always interesting what gets picked up by social media, though – I tend to get more surprised by what gets passed around than by what gets overlooked. There was a dune image recently that got a lot of play because it looked a bit like the Starfleet insignia, for instance. But I am always really pleased when HiRISE images pop up in my twitter feed.

What's the most surprising image so far, either in scientific content or in appearance?

We've seen lots of features that surprised us when we saw them up close in HiRISE images. I remember attending an informal talk here at JPL of HiRISE images shortly after MRO arrived in orbit, and everyone was discussing interpretations of features. One image came up – of dust streaks on a slope, I think – and there was silence. Then one of the audience members said "now, that's just wrong!"

I think the Recurring Slope Lineae (RSL) are the biggest surprise scientifically – these are active features, probably involving liquid water in some way.

Can you give me an example of a surface image that was particularly challenging to obtain?

I'm particularly proud of the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) parachute image – I wrote about taking it on the MRO blog.

Was there an instance when selecting an observation was particularly controversial among the team members? How did it get resolved?

Once of the great things about being an orbital mission is that you will come back to the same location under close to the same viewing geometry again and again. Contrast that with a touring mission like Cassini, where every moment of the spacecraft's trajectory is unique and you may never see that particular spot on this particular moon again. So on HiRISE the scientists take turns deciding what images will be taken in each planning cycle (drawing from a database of potential targets that anyone, including the public, can submit suggestions to – this is a blatant plug for HiWish). When it's a good time of year to take polar targets, then the polar scientists tend to sign up for those planning cycles. Otherwise, if a team member is a big fan of volcanic targets, it's generally understood that he or she gets to put in as many of those as can fit for his or her two-week planning cycle. Every team member has the opportunity to put their favorite target on the list to be given extra-high-priority in a particular cycle, so I don't think there's a lot of controversy over individual observations. If it doesn't get in this cycle, you try again next cycle.

Special sequences like our Phoenix and Mars Science Laboratory parachute images or the comet images get a lot more scrutiny, but that's because they are so tricky – we're making the spacecraft do a much bigger roll than usual and trying to take pictures that we didn't design the camera to take- and its a case of all hands on the planning deck to figure out the right settings for those. Our Principle Investigator (PI), Alfred McEwan, gets the final say on things like that.

Has participation in the HiWish program continued at a high rate? What's the current observation requested / fulfilled ratio?

I think there was an initial spike of HiWish requests that has since died down, but we certainly still have more coming in and in every MRO planning cycle we do take images that were suggested by the public. I'm not sure what the ratio is, though. We always welcome new requests!

How much longer can we realistically expect HiRISE and MRO to deliver science?

Well, HiRISE has only lost one out of 14 CCDs [image sensors] in eight years of operating! So hopefully we can keep going for many more years (pending funding). MRO still has a lot of fuel, but we're starting to switch to some of our redundant hardware, including our radio transponder and our inertial measurement unit. The IMU is part of what allows us to have enough control and knowledge of the spacecraft position to be able to target HiRISE so precisely.

When it approaches, will the end of the mission provide an opportunity for observations that otherwise would be considered too risky? (Kind of like Cassini flying inside Saturn's rings during the last orbits.)

MRO also has the responsibility of relaying data for the rovers, and for collecting as much data on potential landing sites as we can, so I don't think they'll let us pull off any wacky hijinks towards the end.

Is there anything else about the preparations for Comet Siding Spring that you'd like to mention? How nervous/excited does the comet make you?

There are some studies underway looking at how many particles we think will be coming in from the comet, and what are the best orientations for the spacecraft to minimize risk of damage from the particles. Once we have a good handle on that, we'll start figuring out what observations we can take – that's the part I'm looking forward to! ISON reminded us how unpredictable comets can be, so I'm going to hold off on being too nervous or too excited for a couple more months. We have people being nervous on MRO's behalf, so I'm just concentrating on when can we start planning images!

My father-in-law is actually a cometary scientist, so I enjoyed having dinner conversations with him about ISON. He's not that interested in Siding Spring because it isn't a sungrazer, we'll see if that changes.

Are there other upcoming events in the next year or so that are especially interesting?

The Mars 2020 potential landing sites campaign is just gearing up, and since I also work on Mars 2020 I'm pretty excited about that!

What areas are you or the science community still hoping that HiRISE can investigate further? In other words, are there certain places on the planet or certain kinds of features that are calling out for more imaging than what you've been able to get to so far?

We want to understand what is causing the many changes that we can see occurring on Mars today – including the RSL, moving dunes, polar avalanches, changing dust streaks, and all sorts of crazy features like springtime CO2 geysers in the polar regions. First we had to figure out that these changes were happening (we had to find them), and then we had to get a sense of where on the planet they were happening and in what seasons, and now we want to monitor them more closely to try to understand why they are happening.

How are HiRISE and MRO faring in the current budget questions?

There's always a budget worry; we are submitting our proposal for our next extended mission very soon, and we'll see how we do. As budgets get cut more and more, we of course can't collect as much scientific data across the board with all of MRO's instruments, and we won't be able to support as many special campaigns like the comet images. I don't want to point to any particular science that won't get done – but we just won't be able to do everything that we do now.

Any more plans for non-Mars shots: Earth, Jupiter, and the like? How about more oblique angle views of the surface?

Any observation that requires rolling MRO by more than 30 degrees take a huge amount of planning, and takes away both from the number of people available to plan our regular images and also the time on the spacecraft for taking our regular images. We're pretty excited about trying to image Comet Siding Spring but there's nothing else on the plan right now – we have a lot of Mars science left to do!

What's the best part of your job? The hardest?

The best part is when the HiRISE team has identified an image or a campaign that needs special attention for whatever reason, and I've shepherded it through documenting the science justification, arguing the science merit with other instrument teams and the spacecraft management, and getting the HiRISE targeting specialists in touch with the correct members of the spacecraft team to put the sequence together – and then the image comes down!

Seeing those images makes me very happy. Horowitz Crater was one of those because we wanted a very large roll (beyond our normal roll limits) on that image, to get a low phase angle to help us get a good look at the RSL in Horowitz.

The hardest part emotionally is when I have to tell someone that we can't get their science observation because of something about the spacecraft constraints, or because a compromise could not be reached between parties. I just had to do that last week. I always want to bring back the best possible science.

The hardest part in general is to make sure that I'm keeping track of all of my tasks, and not letting anything slip through the cracks. I do a lot of juggling.

Does exploring Mars still excite you?

It does! Mars can be so much like Earth and yet so entirely different, depending on where you are looking and what time period you are thinking about.

It's really fascinating.

HiRISE has done a lot of outreach, and in a very timely way. Is there a perception among team members that it has been successful?

I think the whole team has been really supportive of HiRISE outreach, and feels that it has been quite successful!

Are there common misconceptions about HiRISE or observing Mars among space enthusiasts that you think could be cleared up?

One thing that I don't think is well-known is that, due to details about how MRO works, there are places on Mars that are exceptionally difficult to observe because we're doing relay for the Curiosity Rover instead. Since Curiosity landed, we've slowly developed some creative methods for observing that allow us to get some observations in this area, but there are still places where we basically have to ask Curiosity to forego a relay pass in order for us to get our science data. (As you can imagine, that's a complex negotiation, because it limits what activities Curiosity can do.)

Are you optimistic about the future of space exploration in the next couple of decades? What are you most hoping to see?

I must be an optimist because I'm really hoping for ultimately both a Europa mission and also for Mars Sample Return.

Being HiRISE investigation scientist covers half of my time, and I am a science systems engineer for the Mars 2020 Rover with the other half. So I'm most hoping to see a successful science and sample caching campaign with Mars 2020, because that will mean that I have done my job well!

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth