Van Kane • Dec 27, 2013

NASA’s New Planetary Mission Woes

Budget cuts slow down the rate of new missions

Space News recently carried an article that described how the mission roadmap laid out in the recently completed Decadal Survey was no longer affordable given cuts to NASA’s budgets. A single large mission threatens to crowd out the start of smaller missions that would enable regular flights. Space News quotes a leading scientist in the field who says, “The result is 'a strategic program that is drawn out in a way that is acceptable to no one.'”

The roadmap in question is for NASA’s heliophysics program, which has a budget about half the size of the planetary science program. The large mission is the Flagship Solar Probe Plus spacecraft that will make multiple close passes to the sun and is expect to have a cost of $1.2B to $1.4B.

However, by changing a few names and details, the article could have been written for NASA’s planetary, astronomy and astrophysics, or Earth science programs. Whether you agree with the politics or not, the budgets for many federal discretionary programs are shrinking. NASA’s budget has not been spared, and the science program budgets are feeling the effects. (For a good summary of the planetary program’s budget woes, see these posts by Casey Dreier on the Planetary Society’s blog: historical trends and current issues.)

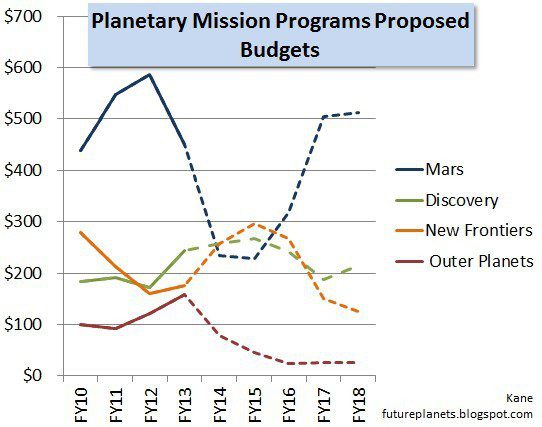

Earlier this decade, NASA completed roadmap plans (called Decadal Surveys) for each of its science programs (except the Earth science program, which completed its Survey in 2007). All the Surveys were told to base their plans on projected budgets that turned out to be wildly optimistic. As a result, the plans included a mixture of large and smaller missions that would ensure frequent flights to explore multiple targets. For the Planetary Science division, the authors of the Decadal Survey recommended for the coming decade development of one to two Flagship missions (in the $1.5B to $2.5B range), two New Frontiers missions (~$1B), and several Discovery missions (~$500M).

If the Planetary Science Division’s budgets had remained at the levels projected when the Survey was drafted, we would be looking forward to an incredibly rich program of missions to many solar system destinations.

Now following the budget cuts, projected budget shows that the Planetary Science Division will struggle to keep missions in development in all three of its size classes. Instead of starting development for six or more new flights to the planets, we will see just three new missions launch through the end of the decade and perhaps only one in the first part of the next decade.

Through 2015, the planetary program will simultaneously develop two smaller missions, the New Frontiers OSIRIS-REx that will return a sample from a primitive asteroid and the Discovery InSight mission that will study the interior of Mars

For the Planetary Science Division, the squeeze will begin in 2016 when it begins to heavily spend on the development of the $1.5B 2020 Mars rover. To afford this large mission, the budget plans show cuts in budgets elsewhere. In 2015, the budget for outer planet missions that funds the continued operation of the Cassini orbiter at Saturn is projected to substantially shrink (see my post here on the potential early termination of the Cassini mission). At the same time, funding to develop future New Frontiers and Discovery missions drops dramatically.

The problem NASA faces is compounded by the funding pattern missions in development follow. While missions typically take four to five years to move from approval to launch, most the funding comes in the middle of years of development in what is known as peak funding. To develop missions that will launch in the early part of the 2020s, NASA needs to be able to meet a peak funding level somewhat greater than $200M at the same time as the 2020 rover hits its (much higher) peak funding needs.

Based on the projected budgets, it appears from NASA’s budget documents that there just won’t be enough money to sustain mission in development in all three of its mission classes at the end of the decade. However, if NASA were to combine projected funding for its New Frontiers and Discovery programs at the end of the decade, it appears that it could support development of one mission along with the 2020 rover.

Based on statements from the Planetary Science Division’s chief, Jim Green, at the just completed American Geophysical Union conference, that appears to be what NASA plans to do. NASA will request proposals for the next (fourth in the series) New Frontiers mission around 2015. NASA would then likely select the winning proposal in late 2016 or 2017. Given approximately five years for development, the new mission likely would launch in 2021 or 2022.

In case the budget situation improves, NASA plans to also complete the preparatory work to request proposals for a Discovery program in the same time frame.

However, the plan for developing a New Frontiers mission at the end of the decade depends on the 2020 rover being developed at a cost near $1.5B. That mission currently is in the early formulation stage and a final budget hasn’t been set. If the rover costs come in substantially higher, then affording simultaneous development of a New Frontiers mission could be difficult at best and or impossible.

It takes so long to plan and develop planetary missions that NASA has limited options for restructuring its program of missions to deal with tightening budgets through the end of this decade. But if fewer dollars to develop missions is the long term story, what other options could NASA explore?

Everyone agrees that having NASA’s planetary science program consumed by a single large mission creates too much risk (what if the mission is lost at launch?). Because a single mission will necessarily explore just a single destination with a small suite of instruments, most of the scientists in the field will be starved for new data. (The 2020 rover, for example, will not explore what drives global climate patterns, explore whether Venus was once habitable, or explore how the planets formed.) NASA also needs to have a cadre of scientists and engineers who have participated in developing missions to become the leaders of future missions. That’s difficult to do with a single mission in development.

One idea that has been discussed within NASA has been to reduce the number of Flagship missions to enable funding more small missions. There’s also been a history of Flagship missions regularly experiencing severe cost overruns, starving the rest of the science program. NASA’s administrator, Charles Bolden, recently told a science advisory panel that NASA can’t afford Flagship missions any more. NASA later explained that NASA was not abandoning Flagship mission and understands that some key science questions can only be tackled with these large missions.

My take is that NASA wants to limit its exposure to Flagship missions for the reasons given above. At the same advisory panel meeting, the Associate Administrator for Science, John Grunsfeld, said he wanted to begin studies that would look at whether substantial portions of high priority Flagship missions could be done as New Frontiers missions (perhaps with a bump of 25% or 50% in the cost cap).

During the Decadal Survey process, a number of mission concepts were studied, (including all those that made the candidate list for New Frontiers missions). No studies were done for New Frontiers-class missions to either Europa or Titan because these destinations were studied as Flagship-class missions. (An analysis of missions for Enceladus suggested that a multi-flyby mission to explore its plumes might fit within a New Frontiers or a New Frontiers-plus budget although the full cost analysis was done for a more expensive Enceladus orbiter.)

Could a New Frontiers mission be done for Europa? The Decadal Survey analysis concluded that a multi-flyby mission for Jupiter’s moon Io could be flown as a New Frontiers mission. An Io mission would have to deal with the same key issues a Europa mission would face – requirements to host both remote sensing and in-situ instruments, the high radiation fields of the inner Jovian system, generating power far from the sun, and communicating large amounts of data back to Earth. The Io Observer study results suggest that a New Frontiers mission for Europa is a credible concept to study. However, compared to the proposed ~$2B Europa Clipper multi-flyby Flagship mission, many key questions about Europa couldn’t be addressed by a single New Frontiers mission.

I compared the instrument list of the Io Observed with the proposed instrument list of the Europa Clipper. If a Europa New Frontiers carried a similar instruments as the Io mission, it might address the key questions for geology (a moderate resolution camera), surface composition (an imaging spectrometer and neutral mass spectrometer), and partially explore questions about the icy shell and ocean (gravity science, magnetometer, plasma spectrometer). However, this would drop the power- and data-hungry ice penetrating radar and high resolution landing site reconnaissance instruments. A New Frontiers mission also might make many fewer flybys than the 30+ planned for the Europa Clipper (the Io Observer concept assumed just six to ten flybys) and might return much less data per flyby. (Note: A mission definition team would likely come up with a different list of instruments than I did in this simple thought experiment.)

Another possibility for NASA would be to include even cheaper missions than Discovery missions in its program mix. A committee of scientists reviewing options for the heliophysics program recommended that NASA develop technology to enable scientific missions with very small spacecraft, SmallSats and CubeSats. I have previously written about the potential and limitations for these small missions that could cost just a few $10Ms for SmallSats and $1Ms for CubeSats. Because of the small size of these spacecraft, the science they could do would be limited. However, several could be flown in a decade increasing the variety of science conducted. Perhaps more importantly, these missions could be used to train a new generation of scientists and engineers to become leaders on larger missions.

Through the end of the decade, NASA’s planetary managers have limited options. They can’t, for example, just dictate a Europa New Frontiers mission without first doing an intense analysis of the concept. They can’t simply decide to introduce SmallSat missions before they know the designs are feasible, the technology is ready, and that there would be scientific value for the money spent. For mission development in the next decade, NASA has time to fully evaluate these options.

If NASA has a similar budget for new mission development in the 2020s as it is projected to have the rest of the decade, then it would have an inflation-adjusted $5B to $6B over the decade. With that funding, it could, for example, fly two to three New Frontiers or New Frontiers-plus missions and approximately four Discovery missions and perhaps several SmallSat missions. It would not be as rich a program as we had in the plusher years of 2000 to 2012. It could be a richer program than we seem likely to develop this decade.

Also, budgets are not fixed. While we have seen that they can go down, they can also go up. Even modest increases of $100M per year over the current projections of ~$1.2B per year would go a long way towards enabling a richer program this decade. If you haven’t participated in thePlanetary Society’s campaign to lobby for increased funding, I encourage you do so.

Appendix: Approved list of New Frontiers missions

One of the tasks for the Decadal Survey was to develop a list of missions that scientists could propose for competitions to select New Frontiers missions. The Survey approved five missions for the next selection (New Frontiers 4) and approved an additional two for the selection after that (New Frontiers 5). The latter are indicated with an asterisk. NASA may consider expanding this list to partially fulfill the goals the Survey identified for recommended Flagship missions such as a mission to Europa (see above).

Inner Planets

Venus Atmospheric Probe and Lander

Lunar South Pole-Aitken Basin Sample Return

*Lunar Geophysical Network

Small Bodies

Comet Surface Sample Return

Trojan Asteroid Tour and Rendezvous

Outer Solar System

Saturn Atmospheric Probe

*Io observer

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth